FEATURE | By Kit Stolz

The Interior Life, Pandemic Era

Tree Bernstein

The viral pandemic that has engulfed much of the developed world has changed Tree Bernstein’s life — she has had to cancel promotion events for her newly-published book of stories — but on the phone from Colorado she sounds far but panicked about COVID-19. For a writer and an artist who has lived around the world despite being “a woman of modest means,” Bernstein frequently brings ironic asides and bursts of laughter into the conversation.

“Life in the pandemic is not that much different for artists,” she said chuckling a little. “Luckily my housemate is also an artist. We go about our business in our respective studios.”

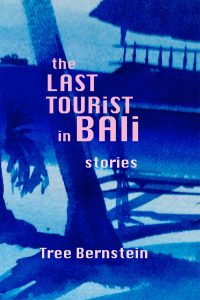

Bernstein lived in Ojai for about a decade, from 2004-2015, while publishing poetry, teaching English at Ventura College and at the now-shuttered Brooks Institute of Photography, and helping to organize numerous readings and events at Bart’s Books, as well as the Ojai Poetry Festival. Her new book of short stories, called “The Last Tourist in Bali,” published this year by Baksun Books, available at the Boulder Book Store on or Amazon, comes from a time in her life when she choose to live for a year in almost complete freedom, leaving the West behind to reside in beauty and ease in Bali on $400 a month.

“In my recollection, now almost 18 years later, 2002 seems so long ago,” she writes in the preface. “A quaint, old-fashioned time. We had cellphones, sure, but people weren’t so involved with them. You had to go to an internet cafe to check email. Social media was unknown. I lived a couple of kilometers from the village at a guest bungalow in a rice field that overlooked the Bali Sea. So much beauty ringed the island with a sleeping volcano at its heart.”

Bernstein’s painterly watchfulness pervades these ten interlinked stories. Raye, a character on a midlife journey — not unlike Bernstein herself — paints in the day and visits the village at night. Time moves slowly on the little-populated east coast of Bali. Raye lets it pass, unworried. She can spend a month painting the field of rice outside her bungalow, just to understand how the golden light of sunset changes as it passes through the fine green rice stalks. “The more she gazes at the field of rice, the more she understands the color is not green at all, but waves of alternating yellow and blue.”

Tree Bernstein’s “The Last Tourist in Bali”

“Bali was rich with so many things I didn’t quite understand,” Bernstein says now, looking back on the experience with a kind of rueful wonder. “I tried to weave my way into life there, and not be a judgy-judge. After a time I began notice that we Westerners were always comparing other cultures against our culture. When you’re in a place where the norms are so different from our own, weird things begin to happen. I don’t believe in ghosts, but I saw ghosts in Bali.”

Over the course of her time in Bali, the character of Raye falls in with a number of characters that she might have judged more critically in another life. These characters include Asa, a Muslim married woman who makes a living in the black market overseeing the smuggling of teak logs. After a bomb in a tourist cafe in a distant city kills dozens of tourists, Raye and Asa find themselves together in the isolated village in a sort of suspended animation. Asa waits for the teak and her money, and Raye waits for the perfect light by which to paint in the evenings. “They admired each other’s patience,” Bernstein writes. A mostly unspoken and unexpected friendship grows in between these two very different women.

The beauty of Bali can hide darker truths. “Too Good for Ubud” tells the story of Dion, a young gay man who liked to dress outrageously, working as a hairdresser in the day, while performing as a lip-synching woman in a bar at night. Raye meets him at the hair salon, and enjoys his campy outrageousness, but neither she nor her gay English friend Clive — who is attracted to Dion — understand the danger Dion is courting. One night Dion is found in an alley, brutally murdered in a knife attack. A devastated Raye pours her heart out to Clive. Clive tries to reassure her over the phone as he is watched by his slim, attractive houseboy Gede — who knows that Clive wants him, and wanted Dion too.

“When [Dion] put on his shimmy-shimmy dress and got all made up,” Raye says, knowing nothing of Gede’s jealousy, “he was the most beautiful girl in Bali.” As sexually sophisticated as both Raye and Clive are, neither can imagine the possibility that Dion was killed for his beauty by someone close to them. So much of Balinese life goes unseen by visitors.

Wordsworth famously claimed that poetry originated in “emotion recollected in tranquility.” Bernstein comes from the world of poetry, and her sentences — written with a transparent simplicity — convey a sense of limpid tranquility. Bernstein sometimes lets an image tell the story. The title story in the collection focuses on a male painter who comes to Bali hoping to be reinspired as an artist, and for a time thinks he has found that inspiration, in the form of a beautiful young Balinese girlfriend. One day she borrows some money and goes shopping with her girlfriends, and comes home with armloads of disposable junk the painter abhors. Suddenly Bali itself seems cheap and plastic, and he impulsively decides he must get away.

“He had almost felt inspired by her, almost wanted to paint her,” writes Bernstein. “Now all that passed like a sigh from the center of his desire … He had no idea about Beauty now. He had no idea who this girl was he’d been making love to. He looked into the future and it was crowded with cheap, ugly stuff. The sea itself a crude cliché — a postcard parody of paradise.”

In her time in Bali — just before coming to Ojai — Bernstein came to think that the Balinese saw much more than they let on about Westerners. The vast inequity between a tourist such as herself — considered “rich” because she could spend $10 or $15 a day — and the Balinese was just another fact of life. Bernstein came to see that the Balinese have traditional ways to survive when the tourists go away, and sly ways of getting what they need when the Westerners return. Even if it meant entering a marriage sure to go bust.

“I thought those [Balinese] girls were much more savvy than their pretty faces showed,” Bernstein comments now. After Bali, serendipity brought Bernstein to Ojai. A car repair forced her to stop in the area for a time. She found a teaching job, a safe and hospitable place to live, and good friends and relations. She looks back on her years in Ojai fondly, in part because the Ojai Quarterly ran for years her unique advice column incorporating the wisdom of the great poets, called “Ask Ms. Metaphor.”

“This allowed me to develop a voice that is not me, to write from the point of view of a know-it-all character. It’s always practical, but my hope with the poetry portion is that it will be interesting enough that the reader will want to pursue it further — I always include a link to the work,” she says now.

In the Ask Ms. Metaphor column (which still runs on Bernstein’s site on-line) in April a letter writer asked if in these pandemic times Americans will become more tolerant of introverts, and stop asking them to be upbeat and social if they’re not in the mood.

Ms. Metaphor replies that labels such as “extrovert” and “introvert” categorize behavior in interesting ways, but have their limits. “Along comes COVID-19, and suddenly the social dance changes — everyone is a wallflower. Truth is, we’re all more complex than an easy check-the-box Type A or Type B personality. Under quarantine, we are learning to become our opposites,” she writes, before going on to quote Wordsworth’s poem about “wandering lonely as a cloud” and coming upon a crowd of daffodils, “ten thousand strong,” and finding a communion for introverts there.

In Boulder now, where in her youth Bernstein studied poetry and literature at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, when asked about advice for writers, Bernstein mentions not craft or agents or promotion but simply persistence. In her teaching she says she often encounters students who want her to tell them what’s wrong with their writing, when part of her wishes that they just trusted their instincts.

“My teachers were the Beats,” she says firmly. “What they taught me was that writing is not done with a particular sort of No. 2 pencil, but just by showing up, by staying in the practice. You may not need another workshop; you might need to just love yourself and your work a little bit more. Get that little tickle of an idea and have the urge to follow it.”

Bernstein laughs again.

“This is a difficult job for someone who wants a relationship,” she adds, sounding a little amused once again by her artist’s life.

Leave A Comment