By Mark Lewis

By Mark Lewis

In the spring of 1972, as the school year was winding down, a University of Chicago graduate student named Jim Churchill contacted his parents in Los Angeles to ask a favor. He wanted to hole up in the family’s weekend house in Ojai that summer while he finished writing his master’s thesis. They said yes, and in due course he arrived in Ojai, prepared to think deep thoughts. But when he got to the house on Thacher Road, he found that someone had left a mess for him to clean up.

“Every ashtray in the house was crammed with a mountain of cigarette butts,” he recalled in an interview. “The garbage disposal was crammed full of chopsticks.”

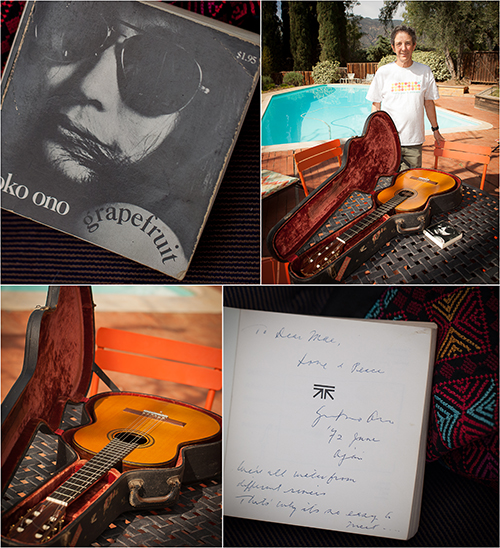

Even more annoyingly, Churchill’s classical guitar, a gift from his parents handcrafted by the master Spanish luthier Manuel Rodriguez, had been left out in the sun by the swimming pool with its case open. Nonplussed, Jim called his mother, Mae Churchill, to find out who had left the house in such disarray.

“Oh,” she replied, “John Lennon was there.”

And Yoko Ono too: She had left behind a copy of her book “Grapefruit,” with a handwritten inscription: “To dear Mae, love and peace, Yoko Ono, ’72 June, Ojai.“

That was 43 years ago, and the Lennons’ Ojai sojourn has long since passed into local legend: While on the run from Richard Nixon, J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI, John and Yoko came here in secret to consult with the philosopher Krishnamurti. They hid out for months in East End seclusion, surfacing occasionally to astonish the locals by dining at the Ranch House, or by jumping onstage to play music in a Ventura bar. Then they disappeared, as mysteriously as they had arrived.

That’s the mythic version, more or less. And some of it really happened. But overall, as is so often the case, the myth has eclipsed the reality. The actual story of the Lennons’ visit is a bit different, although no less interesting.

Little of it can be gleaned from the many books written about John Lennon. A few of his biographers mention the Ojai episode, but only in passing. Most of them omit it altogether. Yoko Ono knows the full story, of course, but she has never been quoted about it, and she declined our request for an interview. Still, the gist of it can be pieced together from various published sources, and by talking to people who had dealings with the Lennons in those days. As it happens, some of those people live right here in Ojai.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon at their home in England, December 1968.

Elephant’s Memory

John Wilcock and Craig Pyes have never encountered one another in Ojai, where both now make their homes. But they have crossed paths in the past.

“I knew him back in the day,” Pyes said of Wilcock. “He was right in the center of things.”

Both men are veterans of America’s underground press scene of the ‘60s and early ‘70s, during a period when John Lennon and Yoko Ono were much in the news.

“I knew Yoko quite well,” Wilcock told the OQ. An Englishman who crossed the pond in the 1950s, Wilcock landed at the brand-new Village Voice in 1955 as one of the original editors and columnists. He first met Ono in the mid ‘60s when she was an avant-garde conceptual artist in New York, and he was editing The East Village Other and then launching his own underground tabloid, Other Scenes.

Wilcock remembers attending Ono’s seminal March 1966 event at the Judson Church in Washington Square, at which visitors were invited to climb into black bags that she had placed on the floor. Wilcock liked her, and he published some of her work in Other Scenes, but he did not regard her as a likely future star.

“She was just somebody around the New York art scene,” he said.

Later in 1966, he encountered her in London, where she had gone to further her career as an artist.

“She had just met Lennon,” he said. “She was very excited about what it might lead to.”

Everyone knows what it led to. Lennon married Ono in 1969 and left the Beatles shortly thereafter. He and Yoko launched their highly publicized “bed-in” campaign, deploying songs like “Give Peace a Chance” to urge an end to the Vietnam War. Their flower-power approach earned them scorn from the increasingly radicalized writers of the underground press — including John Wilcock, who gently chided their naiveté in the March 1970 issue of Other Scenes.

“My own column suggested mildly that John Lennon and Yoko Ono lying around in a hotel suite and renting billboards protesting the war was not the most revolutionary of actions,” Wilcock wrote in his memoir “Manhattan Memories.”

Lennon’s response to this sort of criticism was “Imagine,” the ultimate flower-power anthem and a huge hit in the fall of 1971, along with the album of the same name. By that point, John and Yoko had moved from England to an apartment on Bank Street in New York’s Greenwich Village. They had come to the U.S. because Yoko was seeking custody of Kyoko, her 8-year-old daughter by her previous marriage to an American named Tony Cox.

Within a few months of the Lennons’ arrival, Tony took Kyoko and went into hiding, pursued by John and Yoko’s lawyers and private investigators. As they waited for news of Kyoko’s whereabouts, the Lennons fell in with a set of New Left activists who began pushing them in a more radical direction. Among their new friends were Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Bobby Seale — and Craig Pyes.

Pyes was visiting New York from his home base in Berkeley to drum up support for a new magazine called SunDance. He and his colleagues wanted to offer a more authentic alternative to Jan Wenner’s Rolling Stone, which they saw as ripping off the counterculture. Their supporters included Rubin and Hoffman, who saw SunDance as a potential house organ for their anti-Nixon crusade.

At the same time, Rubin and Hoffman were trying to enlist Lennon in a Yippie-style concert tour that would disrupt the upcoming Republican National Convention (at which Nixon would be re-nominated for president). Ever the networker, Rubin brought Pyes to the Lennons’ Bank Street apartment one day, to see whether John and Yoko could be persuaded to write a column for SunDance.

Lennon played Pyes two new songs he had written — explicitly political songs about the Attica prison riot and about Northern Ireland, written for an album John and Yoko were recording with a New York band called Elephant’s Memory.

As Pyes was leaving, he asked whether the Lennons would write for SunDance. John replied that he and Yoko already had an offer from Esquire, an established magazine with a big circulation. Why should they write for a start-up instead of Esquire?

“Because they’re pig media,” Pyes said he replied. “And he says, ‘Well, OK.’ ”

When the first issue of SunDance came out in April 1972, it included a column by John and Yoko on the women’s movement. By that point, John already had been identified as an enemy by the Nixon administration and targeted for deportation.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service cited John’s 1968 conviction for marijuana possession in England as grounds to deny him a visa extension. Lennon hired a lawyer to argue his case.

“I don’t know whether there is any mercy to plead for because this isn’t a federal court, but if there is, I’d like it please,” John said on May 17, during an INS hearing in New York.

The Lennons now found themselves with some free time on their hands. The INS decision in John’s case was not expected for several months. The couple had finished work on their upcoming album, and they had abandoned the idea of mounting an anti-Nixon summer concert tour. John and Yoko decided to drop out of sight and hit the road for California in their new Chrysler station wagon. They could enjoy a much-needed vacation, and see a bit of America while they were at it.

“I needed to go in some of the coffee shops at four in the morning and get a chocolate milkshake, that kind of thing, just do it normally like the rest of the people do,” John later told biographer Ray Coleman. “Yoko and I wanted to experience the heartland of this country.”

They also wanted to spend some time in a secluded place where they could wean themselves from their mutual addiction to methadone. They asked their lawyer to find them a rental house in Southern California, in a private setting where they would be safe from the prying eyes of the FBI agents who were always shadowing them in New York. Why Southern California? Because the Lennons recently had received a tip that the elusive Tony Cox was holed up with Kyoko somewhere in Granada Hills, on the outskirts of Los Angeles.

Thus it was that one day in the second half of May, John and Yoko piled into the back seat of their dark green Town & Country station wagon and headed west, with their assistant Peter Bendry at the wheel. The car had no built-in stereo system — instead, John played 45 RPM singles on a portable turntable, and the needle jumped every time the car hit a bump. Thus equipped, the Lennons embarked upon the cross-country odyssey that would deliver them to the hideout their lawyer had found for them, in an out-of-the-way town called Ojai.

East End Haven

The house on Thacher Road already had an interesting history. It had been built in the Craftsman style in 1905 for Charles G. Penney, a retired Army general and a Civil War veteran. After Penney died in 1926, the house eventually was acquired by a retired Vassar philosophy professor named Guido Ferrando and his wife, Erica, an interpretive dancer. In 1946, Dr. Ferrando became the first headmaster of the Happy Valley School (now the Besant Hill School), which he co-founded with Aldous Huxley, Krishnamurti, Rosalind Rajagopal and others.

The Ferrandos’ circle overlapped with that of the English actress-poet Iris Tree, a daughter of the famous theatrical impresario Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree. Iris had brought the former Chekhov Players to Ojai. They sometimes rehearsed their plays in a little studio behind the Ferrandos’ house. The Santa Barbara memoirist Erika Moore recalled a night she spent there just after the war, when the Ferrandos invited her to Ojai to hear Krishnamurti speak:

“Their house was filled with antiques, mostly from Italy. Angels and Madonnas prevailed. I fell into their atmosphere like into a soft cloud. Guests were appearing for dinner. Erika and Woody Chambliss, Alan Harkness and wife, he being the director of Ojai’s High Valley Theatre. Then there was the wandering poet-minstrel, Norbert Schiller,” Moore wrote. “Naturally, the talk was of Krishnamurti … “

By 1956 the Ferrandos had moved on and the house had passed into the possession of a Los Angeles couple, Robert and Mae Churchill. Robert was a Harvard-trained lawyer turned filmmaker, who specialized in educational films; Mae had an economics Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania and an activist’s commitment to liberal causes. Their daughter, Joan, attended the Happy Valley School; their son, Jim, attended the Ojai Valley School.

The Churchills moved back to L.A. in 1961, but they kept the Ojai house as a weekend place, and often entertained friends there. Mae’s guests tended to be fellow activists, one of whom eventually provided the connection that brought John and Yoko to Ojai. Jim Churchill identifies the intermediary as Ralph Caprio, a friend of Mae’s from Chicago.

“He knew the Lennons’ lawyer,” Jim said. “And he knew about the house. So he hooked it up. And my mom said yes.”

Thus it was that one day in late May or early June of 1972 — the exact date is unknown — a dusty Chrysler station wagon delivered a road-weary John Lennon and Yoko Ono to Ojai.

From upper left: Yoko and John Lennon’s “Grapefruit” album cover; Jim Churchill with Lennon’s guitar, the handwritten note he left behind after holing up at the East End house, the guitar in its case.

John at the Beach

Dan Cole has lived in Ojai for most of his life, but in June 1972 he was living on Montauk Lane in Ventura and was a happy-hour regular at John’s At the Beach, a popular pub owned by John Blonder on nearby Seaward Avenue. Cole was at the bar having a drink one evening while local musician Trevor Jones held forth from a small stage. It was a Tuesday, so the crowd was sparse. When Jones took a break, a longhaired stranger got up with a guitar and started singing “Norwegian Wood.” No one paid much attention at first, but then some young women sitting near the stage took a closer look and sounded the alarm: “That’s John Lennon!”

Yoko was there, too, but she left the singing to her husband. He played a couple of songs and then they left. Cole looked out the window, perhaps expecting to see Lennon depart in a limo, or in something like the famous psychedelic, multicolored Bentley he drove in England. There was nothing of the sort parked on Seaward Avenue. “He drove off in a station wagon,” Cole recalled.

Two nights later the Lennons were back, and John played another brief set, this time backed by some local musicians. Cole wasn’t there that night, but he showed up the following night to find the place jammed with people. Word had spread about Lennon’s earlier performances, and everyone was hoping that lightning would strike a third time. But John and Yoko never returned to John’s At the Beach.

Back in Ojai, there were Lennon sightings at the Ranch House restaurant in Meiners Oaks.

“They ate several times at the Ranch House, mostly lunch,” recalls the restaurant’s former owner David Skaggs, who worked there at the time. “They enjoyed the table for two right beside the koi pond. They were a very quiet couple, but didn’t seen to get annoyed with any attention that came their way.”

From time to time, John sauntered forth from the Churchill house to explore the East End on foot. Local resident Cary Sterling was stunned one day when he stumbled upon the erstwhile Beatle on McAndrew Road near the Thacher Creek bridge.

That bridge in later years would be the setting for several legends arising from Lennon’s visit. In those days it had guardrails made with redwood posts on which people sometimes carved their names. At some point — whether it was Lennon in 1972 or another person at a later date — someone carved “John Lennon” on the top of the west-side rail, where passersby often stood and watched the sunset. When the bridge was replaced in the 1990s, one longtime Ojai resident (who prefers to remain anonymous) cut out the section with Lennon’s name, and kept it as a souvenir.

“I’ve got it still,” he told the OQ, “although there’s no way to authenticate it.”

Despite persistent legends, one place John and Yoko evidently did not visit was Krishnamurti’s East End complex. Krishnamurti was in Europe at the time, and his former (and future) home in Ojai was then in the hands of his estranged business manager D. Rajagopal and Rajagopal’s wife, Rosalind. Nor is there any evidence to suggest that Lennon and Krishnamurti ever met anywhere else. But people who cherish the idea of a connection between these two iconic figures can console themselves with this thought: Krishnamurti likely had passed some pleasant evenings in the Churchill house many years earlier, when it was still owned by Guido Ferrando. So in a sense, the philosopher and the Beatle did inhabit the same space in Ojai, just not at the same time.

For Mae Churchill, John and Yoko were less than ideal tenants. They annoyed the property’s caretakers, Charles and Mary Miller, by trying to order room service, as though they were staying in a hotel. According to at least two published reports, they hosted a large crowd of hangers-on at the house and ran up an enormous phone bill. But Mae agreed to meet them for tea one day at the Pierpont Inn in Ventura. According to Joan Churchill, John and Yoko were intrigued by the books Mae had at the house, and wanted to meet their owner.

“All I remember Mae saying about the meeting was that John was phobic about handling money,” Joan said.

The Lennons hoped to talk her into extending their stay, but Mae refused. Her son needed the house to write his thesis, and that was that. They were out.

It should be noted that John and Yoko were not really “on the run” from Nixon’s FBI in June 1972. Their lawyer was waging an effective legal fight against the deportation order. They had gone on the Dick Cavett show as recently as May 11 to make their case to a nationwide television audience. And they were about to release a new album on June 12 — “Some Time in New York City,” the much-anticipated follow-up to “Imagine.” They were not being hunted — they were in fact the hunters, having come to Ojai primarily to track down Yoko’s ex-husband and daughter, with the help of a phalanx of private detectives.

On the other hand, John and Yoko did have high expectations for “Some Time in New York City,” and they might have been preparing for the possibility of a backlash.

Here was the immensely popular John Lennon, still wreathed in his Beatles halo, still basking in the afterglow of “Imagine,” and he was about to release an overtly political album that embraced a New Left agenda. The voting age had just been lowered to 18, enfranchising millions of teenagers who habitually took their cues from rock stars. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin hoped that enlisting Lennon in their Rock Liberation Front might galvanize the left, possibly enough to derail Nixon’s re-election campaign. The Nixon administration evidently feared that possibility enough to seek Lennon’s deportation. So John and Yoko could be forgiven if they thought they were about to detonate a bomb that might in some sense change the world. When it went off on June 12, they would look on from their Ojai hideout and see what happened.

It’s not easy to publicize a new album while in hiding, but the Lennons gave it a shot. They sent their chauffeur, Peter Bendry, to the Music Box store in the Arcade to have an advance copy of the LP converted into an eight-track tape. Drew Robertson, who worked at the Music Box at the time, recalls being unimpressed by the Lennons’ new music.

“I just heard parts of it,” Robertson told the OQ. “It didn’t really appeal to me.”

The Lennons also placed a call to an L.A. radio DJ named Elliot Mintz, with whom they already had a long-distance telephone relationship. When Mintz came on the line, Yoko carefully pronounced the name of the obscure little town she was calling from.

“One day they called me and said, ‘We’re in California and we want to meet you,’ ” Mintz told the OQ. “And they said, ‘We’re in a place called O-hi.’ ”

Mintz already was familiar with Ojai, having come here to hear Krishnamurti speak and to dine at the Ranch House. (It was Mintz, apparently, who turned the Lennons on to the legendary restaurant.) Eager to meet the famous couple in person, he drove up from L.A. on June 9. Evidently as a security precaution, they did not give him the address. Instead, following their instructions, he met them at a pre-determined rendezvous spot, then followed their station wagon to the house on Thacher Road.

“It just seemed to be a house in the middle of nowhere,” he said.

At one point that day, the Lennons drew him into the bathroom, turned on the faucets, and whispered that they feared the house had been bugged by the FBI. They also gave him an advance copy of “Some Time in New York City.” Mintz drove back to L.A., played the entire album on his radio show without commercial interruption, and was promptly fired. This was a promising start for John and Yoko (if not necessarily for Mintz). It seemed as though they had struck a nerve.

Meanwhile, they and their detectives continued to look for Kyoko. Albert Goldman, in his controversial 1988 biography “The Lives of John Lennon,” portrays John and Yoko and their minions as Keystone kops chasing Tony Cox around the San Fernando Valley:

“This was Tony’s first hiding place, and this is where the Lennons sought to trap him, their house in Ojai being only a half-hour’s drive [sic] from Granada Hills. Like most amateur adventurers, the Lennons were very clumsy with their cloaks and daggers. After a month of vain endeavors to snatch their elusive prey, during which they trashed the beautiful house in which they were staying and were expelled by its irate owner, John and Yoko got word that Tony was in Sausalito.”

Goldman’s biography has been widely dismissed as a mean-spirited hatchet job, but at least one person in Ojai vouches for its accuracy — John Wilcock, who worked for Goldman as a researcher on the book, and who defends its author as “a first-rate biographer.” In any case, Goldman was right about the Sausalito tip. The Lennons left Ojai in a hurry in mid-June, which may explain why they left such a mess behind. Apart from the overflowing ashtrays, the chopsticks in the disposal, and the guitar left out by the pool, they also left a lot of clothes in the bedroom they had been using.

“I remember in particular a pair of pale buckskin boots with long fringe,” Joan Churchill said.

The Lennons headed north in their station wagon, and they took the newly unemployed Elliot Mintz with them. (Lennon to Mintz: “Pack a bag and join the circus.”) That marked the end of the Lennons’ Ojai sojourn. It had lasted three weeks at the most, and possibly less than two.

The Chase Continues

After arriving in San Francisco, John and Yoko telephoned their SunDance editor Craig Pyes and pressed him into service.

“That first time we met, we talked nonstop for five or six hours,” Pyes said. “It’s etched in my mind as one of the greatest experiences of my life.”

“To be with [Lennon] was just an overwhelming experience,” Pyes added. “His personality was intense. There was this incredible openness.”

The Lennons rented a house in Mill Valley and spent a lot of time in the back seat of Pyes’s Volkswagen Beetle, roaming Sausalito in another fruitless search for Kyoko. In mid-summer they went back to New York.

They continued to hobnob with Jerry Rubin, but they were not really committed to radical politics, at least not in any practical way.

“Absolutely not,” Pyes said. “They were artists. Politics [to them] was just another form of art.”

Alas, art and politics do not always mix well. “Some Time in New York City” had turned out to be a humiliating flop. Even left-wing rock critics condemned its songs as artless agitprop. The record-buying public agreed; the album rose no higher than No. 48 on the U.S. album charts, spawned no hit singles and had no discernible impact on the career of Richard Nixon, who was overwhelmingly re-elected in November 1972.

In 1973, John and Yoko separated, and John took up with Yoko’s assistant May Pang. He moved to Los Angeles with Pang and commenced a 15-month bender that in retrospect he would characterize as his “lost weekend” period. There are stories told in Ojai that Lennon and Pang passed some time here during this period. But Pang, through a spokeswoman, told the OQ that she has no memory of ever being in Ojai.

By 1975, John was back in New York and back with Yoko. In the wake of the “Some Time in New York City” debacle, he had retreated from activism and released three non-political solo albums (“Mind Games,” “Walls And Bridges” and “Rock ‘n’ Roll”). All of them sold reasonably well; none was considered a masterpiece.

When Pete Hamill interviewed Lennon for Rolling Stone in June 1975, he asked John how his ealy ‘70s radical phase had affected his music.

“It almost ruined it, in a way,” Lennon said. “It became journalism and not poetry.”

Then Lennon lapsed into silence. He won his INS case, got his green card, fathered a child with his wife, and devoted himself to family life. For almost five years, he released no albums, delivered no live performances, led no protests, granted no major media interviews.

Many onetime admirers felt disappointed, even betrayed. In November 1980, the writer (and future Ojai resident) Laurence Shames published a cover story in Esquire depicting Lennon as a pathetic sell-out who had let his admirers down by withdrawing from public life. Formerly the “emblem and conscience of his age,” Lennon now seemed to have abandoned his idealism to embrace the cossetted life of a self-centered millionaire:

“The Lennon I would have found is a 40-year-old businessman who watches a lot of television, who’s got $150 million, a son whom he dotes on, and a wife who intercepts his phone calls,” Shames wrote. “He’s got good lawyers to squeeze him through tax loopholes, and he’s learned the political advantages of silence.”

Lennon would not grant him an interview, so Shames posed a rhetorical question in his article: “Is it true, John? Have you really given up?”

Shames could hardly have anticipated the effect his words would have on Mark David Chapman, a mentally unstable security guard from Honolulu who idolized Lennon. Reading the Esquire article helped persuade Chapman that his hero was a phony.

As the article hit the newsstands, Lennon already was preparing to return to public life, and in a big way. In early December, he and Yoko released a new album, “Double Fantasy,” which shot up to No. 1. One of its songs, “Watching the Wheels,” contained an answer to his critics: “No longer riding on the merry-go-round — I just had to let it go.”

While doing publicity for the new album, Lennon (in a Rolling Stone interview) delivered an explicit riposte to the Esquire article:

“That guy is the kind of person who used to be in love with you — you know, one of those people — and now hates you — a rejected lover. I don’t even know [Shames], but he spent his whole time looking for an illusion that he created of me, and then got upset because he couldn’t find it.”

Lennon said some fans wanted him to be a martyr for their unfulfilled dreams: “What they want is dead heroes, like Sid Vicious and James Dean. I’m not interested in being a dead fucking hero.”

Three days later, Chapman gunned him down.

Aftermath

In the fall of 2001, writer Kit Stolz was preparing an article about Lennon for the short-lived Ojai Magazine. Stolz requested an interview with Ono, but she did not respond, so he went ahead and published the piece.

“Six months after it was published, she calls me up and says, ‘Oh, I hear you’re writing a story,’ “ he told the OQ. “I was stunned.”

Caught off-guard, and with his article already in print, Stolz did not ask her many questions about her time in Ojai. But he did ask if she planned to write a memoir one day.

“She said, ‘No, I’m not going back,’ or words to that effect,” Stolz recalled. “She was really nice. She said, ‘Well, have a great life,’ and hung up.”

Ono recently celebrated her 80th birthday and is still going strong. True to her word, she has not published a memoir.

2001 was also the year John Wilcock moved to the Ojai Valley. Unlike Ono, he did publish a memoir — “Manhattan Memories,” which came out in 2010. At 87 he is still posting material on his website, ojaiorange.com, which he bills as “The Ongoing Journal of John Wilcock, the Peripatetic Patriarch of the Free Press.”

SunDance magazine folded after only three issues, but Craig Pyes went on to a notable career as an investigative reporter, winning two Pulitzer Prizes while at the New York Times. He later became a licensed private investigator, moving to Ojai in 2010 and setting up shop as Pyes Only, a boutique firm specializing in human-rights, missing-persons and public-interest investigations. He has yet to write his memoirs.

Laurence Shames went on to write many books, both as a ghostwriter and (under his own name) as the author of mystery novels set in Key West. A longtime Ojai resident, he recently moved to Asheville, N.C. He declined to comment for this article. “Sorry, but I have nothing to add to what’s in the Esquire piece, and the subject is a painful one for me,” he told the OQ via Facebook.

Mae Churchill died in 1996, and was eulogized in The Los Angeles Times as a prominent activist “for privacy and other civil rights.” The house on Thacher Road now belongs to Joan Churchill, a distinguished documentary filmmaker and cinematographer based in Los Angeles. The house is available as a vacation rental, and its website highlights its history by mentioning its former owners General Charles G. Penney and Dr. Guido Ferrando. The website makes no reference whatsoever to John Lennon or Yoko Ono.

Jim Churchill returned to Ojai in the late ‘70s. He and his wife, Lisa Brenneis, are founding members of the Ojai Pixie Tangerine Growers’ Association. He still has the guitar that Lennon left out by the pool, and the copy of “Grapefruit” that Ono left behind for his mother. In her inscription, Ono quoted from one of her songs on “Some Time in New York City.” “We’re all water from different rivers,” she wrote. “That’s why it’s so easy to meet.”

Lovely to read about this – I have just come to Ojai for a week from the UK and picked up that John and Yoko had a connection with the place, and your article helped separate the truth from the myth!