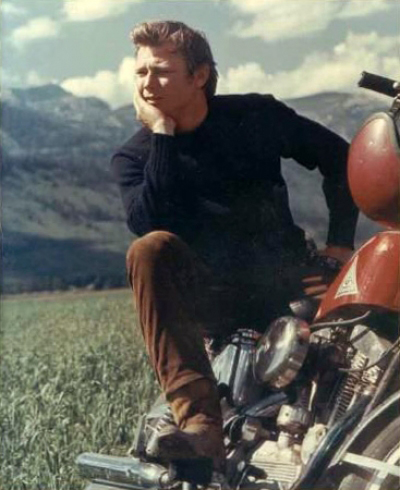

Michael Parks in a publicity still from “Then Came Bronson.”

By Mark Lewis

At the end of his life, Michael Parks was famous for not being famous. When the veteran character actor died last May at 77, major newspapers ran prominent obituaries lauding his brief but indelible appearances in several Quentin Tarantino films, and his memorable turn in a supporting role on the original “Twin Peaks.” The subtext: great actor, inexplicably obscure. But back in the ‘60s, when Parks was living in Ojai, he really was famous. This is the story of a talented (but stubborn) man who destroyed his own career – twice! – yet bounced back to forge an unlikely third act, on his own terms.

Michael Parks watched the video of himself riding a Tennessee walking horse across a bridge, while his newly released hit single supplied the soundtrack. “Going down that long, lonesome highway,” he heard himself sing. “Gonna live life my way.” The date was March 25, 1970 – a Wednesday evening, sometime between 9 and 10 p.m. – and Parks was a guest on the very popular “Johnny Cash Show.” Parks’ own series, “Then Came Bronson,” would come on next, in the 10 to 11 p.m. slot. The network had just announced the show’s cancellation, but Parks had not been happy with it anyway. Now he would be free to collaborate on a screenplay with his friend Terry Southern, screenwriter of “Dr. Strangelove” and “Easy Rider;” or perhaps make a film with his friend Jean Renoir, the great French director of “The Grand Illusion” and “The Rules of the Game.”

The timing seemed perfect for Parks. The old Hollywood, the studio system, was dead; the 1970s would belong to a new generation of iconoclastic auteurs, and Parks should fit right in. At 30, he looked like James Dean, mumbled like Marlon Brando, smoldered like Montgomery Clift. How could he miss? Inevitably the world would beat a path to his door, which at the time was located at 515 Foothill Road in Ojai, just up the street from the Presbyterian Church.

Meanwhile, he could watch himself on the “Johnny Cash Show,” where the video had moved on from Parks on the horse to Parks and Cash sharing a motorcycle, apparently having the time of their lives. On “Bronson,” Parks played a disillusioned newspaper reporter who quits his job to roam the west on a Harley. Clearly, Cash was a big fan of the show. “Then came Bronson back to Tennessee,” the singer intoned in his rich baritone, supplying the voiceover for the video. “And you know it looks like he fell in love with the place. Well, everybody sure fell in love with him.”

People were always falling in love with Michael Parks. Unfortunately, some people also fell out of love with him – powerful people like Lew Wasserman, the mighty Universal Studios mogul; and John Huston, the legendary director; and more recently the “Bronson” producers. Parks had a well-earned reputation for being difficult.

“Michael hated control,” recalls his friend Keith Nightingale, of Ojai. “He hated anybody telling him what to do or how to do it.”

To Parks, it was simple: He had a gift. People should get out of his way and let him use it. Brando did things his way and got away with it; why couldn’t Parks? But he had forgotten Step 1 of Brando’s approach: First, become a star.

WILD ABOUT HARRY

Harry Samuel Parks was born in Corona in Riverside County on April 24, 1940, the son of a former big-league baseball prospect now reduced to itinerant laborer. Harry later estimated that he attended 20 different schools in California before finally dropping out at 15. He hit the road and took whatever jobs he could find: picking fruit, upholstering caskets for a mortuary, declaiming poetry in a San Francisco coffee house. Somewhere along the way, he caught the acting bug, and eventually landed in the theater department at El Camino College, near Torrance.

“I met Harry in June 1959,” recalls Natelle Carlino. “El Camino Junior College was performing ‘Kiss Me Kate.’ I was Bianca. He was some kind of clown.”

The following year, they co-starred in a local production of “Compulsion.” Harry played a sensitive young man who commits a murder just for the thrill of it.

“He and I had a love scene, that’s what I remember,” Carlino says.

Harry Parks stood out at El Camino, in part because he was so good looking. But he also had talent. “He was intelligent, creative and complicated,” Carlino says. “He was a remarkable actor! Always was.”

Parks’ performance in “Compulsion” led to his discovery by a big-time Hollywood agent, Jack Fields, who changed his first name from Harry to Michael to avoid any possible confusion with the actor Larry Parks. Almost immediately, the newly rechristened Michael Parks found himself up for the lead role of Tony in the film version of “West Side Story.” The part ultimately went to Richard Beymer, but Parks was making an impression — on Beymer, among others. Thirty years later, when both actors were in “Twin Peaks,” Beymer reminisced to series co-creator Mark Frost about the tough-guy aura Parks had projected as a young man.

“Richard said he was the scariest actor in Hollywood,” Frost recalls.

FATHER FIGURE

Woody Chambliss (1914-1981) was a native Texan who had trained as an actor in England under Michael Chekhov, and later appeared on Broadway. Chambliss and his wife, Erika, settled in Ojai in the early 1940s, along with other former members of the Chekhov Players troupe, including Iris Tree, Ford Rainey and Hurd Hatfield. This group eventually dispersed, but the Chamblisses stayed on in Ojai, where they raised their family in the East End while Woody managed the Senior Canyon Mutual Water Co. He also kept his hand in as an actor, most notably with a recurring role on “Gunsmoke.” As it happens, his agent was Jack Fields, which is how he came to know Parks.

“August of 1962 is when Michael Parks first came to Ojai,” says Woody’s son Michael Chambliss. “He came up here and went deer hunting with us.”

Parks became a frequent visitor. He enjoyed socializing with Woody’s sons and their friend and neighbor Keith Nightingale, but was it was Woody himself who was the main attraction.

“My dad was like a father figure for him,” Chambliss says.

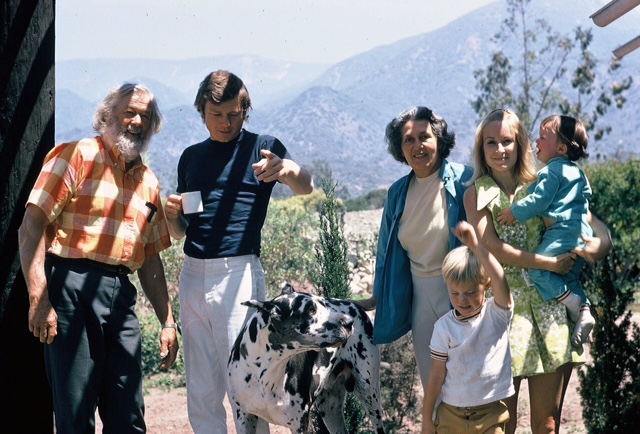

Woody Chambliss and Michael Parks with their families. Chambliss was a father figure to Parks.

Parks had not yet broken through in Hollywood, but he was confident that he was going to make it big.

“I remember hiking with him, and he was talking about how he was going to be a star,” Chambliss says. “I was skeptical, but he started getting parts.”

Big parts, too, as a guest star on prominent shows like “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour,” “Perry Mason” and “Route 66.” Parks had looks, charisma and talent; people noticed. By 1963, he had popped up on the radar screen of Lew Wasserman, who signed him to a contract at Universal and started giving him the big buildup as a leading man in feature films. Parks had star billing in his very first film, “Wild Seed,” in which Woody Chambliss had a supporting role.

“ ‘Another James Dean,’ they are saying at Universal Studios about somber, taciturn Michael Parks, a 25-year-old who clawed his way out of the poverty jungle,” syndicated Hollywood columnist Erskine Johnson wrote in March 1964, as “Wild Seed” was wrapping.

If Parks was somber and taciturn, there was a reason. He started work on the film shortly after marrying the actress Jan Moriarty. Only eight weeks later, he came home from the set to find her dead of an overdose of pills. The coroner’s verdict was suicide.

“He’s wondering,” Johnson wrote, “whether things would have been different if he hadn’t been discovered as a star.”

Parks dealt with his wife’s death by plunging back into work. He starred opposite Ann-Margret in “Bus Riley’s Back in Town,” Jennifer Jones in “The Idol” and Faye Dunaway in “The Happening.” But Parks’ biggest splash came courtesy of John Huston, who picked him to play Adam in “The Bible.”

“That was his big break,” Nightingale says.

Bruce Dern once told an interviewer that when he and Jack Nicholson were struggling young actors, they always thought Parks was the one among their peer group who was the most likely to make it big. Dern’s then wife Diane Ladd (who nowadays lives in Ojai) says she agreed.

“He was the new Jimmy Dean, and Bruce and I and everyone loved him,” Ladd says.

But few of Parks’ early films were hits, and already he was causing trouble. He sparred with Huston on the set of “The Bible,” and he refused Wasserman’s demand that his next film be a remake of “Beau Geste.”

“He turned down a lot of parts,” Nightingale says. “Woody told me that he thought Michael really blew it.”

Parks only wanted to play characters he thought were interesting, and only if he was allowed the freedom to shape the character himself.

“He was an actor’s actor,” dedicated to finding “the truth” in a character, Ladd says. “I am sure that made Hollywood tough for him.”

And vice versa. Wasserman, for one, was unhappy with Parks’ attitude, and Wasserman was the most powerful man in Hollywood. Just like that, Parks’ three-year run as a budding movie star was over.

He retreated to television and, increasingly, to Ojai, where he rented a series of houses in the East End. He readily socialized with Woody’s and Erika’s social circle, which included Dee Volz, a former M-G-M dancer turned Ojai Valley News journalist.

“There was something very lovely about Michael,” Volz recalls. “He was just so honest. I always loved Michael because he had had a painful childhood and he was overcoming it.”

There was more pain to overcome for Parks early in 1968 when his younger brother James, with whom he was close, died in a diving accident near Santa Barbara. Woody Chambliss accompanied Parks to the morgue, and later told Nightingale that an agitated Parks had burst into the operating room while the autopsy was still in progress.

“Michael was just totally distraught,” Nightingale says.

Ojai offered a refuge from life’s cruelties. By the summer of 1968, Parks was ready to put down serious roots here. He had a new wife, Kay; her two young daughters, Patricia and Stephanie, from a previous marriage; and a newborn son, James, named for Parks’ late brother. Parks wanted to give them the safe, stable home life he never had as a child, while remaining close enough to Hollywood to earn a living. That August, he bought the house on Foothill Road. It had three bedrooms, two fireplaces, and room enough in the back yard for Parks to put in a corral so his daughters could have a horse to ride.

“He moved to Ojai to provide a good family community for his children, while being available for acting employment,” Natelle Carlino says. (She would move to Ojai herself a few years later, for similar reasons.)

Alas, acting jobs were scarce for an actor labeled “difficult.” Parks had blown his first big opportunity in the business, and how many people ever get a second one? Thus the surprise when he was offered the lead in a new TV series being developed for NBC. His co-star would be a red Harley-Davidson Sportster.

THEN CAME BRONSON

Many people recall “Bronson” as a TV rip-off of the film “Easy Rider,” which starred Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper as hippie bikers on an epic trek across America. In fact, the two projects were developed simultaneously in 1968, and the TV show was first out of the gate; the pilot aired on March 24, 1969, four months ahead of the film’s July premiere. “Easy Rider” was a huge hit that summer, which made “Bronson” seem very au courant when it debuted in September as a weekly one-hour drama.

In the pilot, Bronson inherits the Harley from a despairing friend (played by Martin Sheen) who jumps off the Golden Gate Bridge. Bronson quits his job and takes off on the bike to figure things out. He encounters a runaway bride played by Bonnie Bedelia and the two join forces, until she decides to resume her regular life. Bronson isn’t ready for that; he rides off into the sunset.

The pilot set the tone for the series with a famous scene where Bronson on his bike pulls up at a stoplight next to a middle-aged man in a station wagon, who asks him whether he’s taking a trip. “Yeah,” Bronson replies.

“Where to?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Wherever I end up, I guess.”

“Man, I wish I was you.”

“Really?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, hang in there,” Bronson says, as he rides off to his next adventure.

Parks reportedly improvised the “hang in there,” in place of the more flowery lines in the script. Almost half a century later, it remains the “Bronson” catchphrase. The series inspired many young Americans to get their own motorcycles and set off on their own adventures. “Easy Rider” looms much larger in the cultural memory, but its anti-hero protagonists were drug dealers who came to violent ends, making them problematic role models for mainstream America. Bronson was more of a straight arrow, albeit a troubled soul, so he had broader appeal.

Diane Ladd, who guest-starred in one episode, remembers Parks as hugely talented.

“He was truly one of the best actors I ever worked with,” she says. “And I’ve worked with a lot.”

“Bronson” was not a huge hit, but it garnered a great deal of attention for Parks, especially in Ojai where he was a popular local celebrity.

Unlike some Hollywood stars who settle here, Parks made a point of being part of the community. Both his stepdaughters attended the St. Thomas Aquinas School, and he donated a motorcycle to be raffled off as part of a school fundraiser. His family often dined together at Donovan’s Stew Pot, in the building now occupied by Nocciola. He did folk dancing at the Art Center. And, when Lis Blackwell and other local teenagers set up a coffee house at the Presbyterian Church so they would have a place to hang out, Parks showed up and volunteered to read poems.

“Everybody was in awe,” Blackwell says. “He was really nice. I couldn’t get over that he would do that.”

Parks also showed up at informal hootenannies in Camp Comfort and elsewhere, to sing with local musicians such as Alan Thornhill and Martin Young. He needed the practice, since he had decided to use “Bronson” as a springboard to a new career as a country singer.

LONG LONESOME HIGHWAY

MGM, the studio that was producing “Bronson” for NBC, also owned a record company, which was more than happy to promote Parks as a country artist in the name of corporate synergy. But Parks did not like the “Bronson” theme song MGM had come up with, so he ended up working with the songwriter James Hendricks, who also lived in Ojai. Hendricks had a song mostly written that he thought might do, so Parks picked him up and drove them both into L.A. to record it. They finished the song on the drive into town.

“We were in his Jeep Wagoneer,” Hendricks says. “And I sang him a little bit of the song, and by the time we got the MGM studio, he was ready to go.”

The resulting single, “Long Lonesome Highway,” became a hit, reaching No. 20 on the Billboard pop chart. Hendricks produced Parks’ first three albums, all on MGM Records and all strong sellers. Parks could have become a genuine country star, Hendricks says:

“He had a way of interpreting a song as an actor that was very believable and very pleasant. But he was hard to record. His voice was so soft and whispery. It was good enough to develop if he had listened to instructions. But he was very contrary about a lot of things.”

Hendricks remembers the “Bronson” producers flying him out to a location in Colorado to help them cajole Parks into completing that week’s episode.

“For some reason he didn’t like a certain script,” Hendricks says. “So he refused to come out of his trailer.”

These kinds of shenanigans already had ruined his film-star career. Now he was throwing away his TV career too, and his singing career along with it.

“He blew it,” Hendricks says. “He blew that whole thing. He could have done so much more had he not been his own worst enemy.”

Diane Ladd does not agree that Parks was at fault.

“Actors are judged very quickly, and usually incorrectly,” Ladd says. “He wasn’t arrogant. He was protective of his talent.”

Everything came to a head in the spring of 1970. Nearing the end of its first season, “Bronson” was losing its time slot to “Hawaii 5-0.” The obvious answer was to move Parks’ series to an easier time slot and perhaps tweak it a little. The producers wanted to make it more of an action-oriented show. Parks wanted out altogether.

“I remember quite vividly when Michael brought up the subject of renewing ‘Bronson,’ ” Nightingale says. “What he really wanted was to make his own independent films.”

Woody and Erika Chambliss urged him to stay with the show. “You’ve got the golden goose here,” they said, as paraphrased by Nightingale. Parks should make a success of “Bronson,” and thus make himself a major star. “Then you can do whatever you want to do.”

Instead, Parks forced the issue by insisting on artistic control. “He wanted to pick the directors, and he wanted to have final control over the editing,” Nightingale says.

Unsurprisingly, the producers balked. They decided to replace Parks with the more pliable Lee Majors. Before they could effect the switch, NBC rendered the issue moot by pulling the plug on the series.

Which brings us back to March 25, 1970, the night Parks made his guest-star appearance on “The Johnny Cash Show.” Michael and Kay most likely watched the show with Woody and Erika at the Chambliss home, as Wednesday night was “Bronson” night, and the two couples generally watched Parks’ show together. Cash was a former Ojai Valley resident, but it is not clear whether he and Parks ever met before Parks traveled to Nashville to tape his appearance on Cash’s show. After the horse-and-Harley video segment ended, Parks was shown singing another song, then he and Cash sang a duet. Then his own show came on at 10, and Parks heard himself reprise “Long Lonesome Highway” over the closing credits.

In retrospect, this was the apogee of Parks’ career. “Long Lonesome Highway” was on its way to being a hit; “Then Came Bronson” still enjoyed plenty of cultural cachet, despite its recent cancellation; Johnny Cash had just gushed over Parks on national TV; and Terry Southern was due in Ojai soon to talk about writing a film for him. Lew Wasserman’s Hollywood was crumbling, and the new wave was ascendant: “Easy Rider” and “Midnight Cowboy” were up for Oscars at the upcoming Academy Awards telecast. This brave new world seemed made for Michael Parks, and he was eager to claim his rightful place in it.

“He probably thought that he could get a job elsewhere without a problem,” Nightingale says. “But at that point, they sort of quietly blackballed him in Hollywood.”

Once again the deadly label: “difficult.” Not even hip young anti-establishment directors wanted to hire actors who wouldn’t take direction. At 515 Foothill Road, the phone stopped ringing. Overnight, Parks went from TV stardom to nowheresville. He would not work again for three years.

AFTERMATH

With no acting jobs in the offing, Parks tried to focus on his singing career. He fired Jim Hendricks as his producer and signed with a new label, Verve, which put out his fourth album. It failed to click. Parks’ singing career had died with “Bronson.” With no TV show on the air to promote his records, the public lost interest.

“People forget very quickly,” Hendricks says.

Tragedy struck Parks again January 1971 when his 9-year-old stepdaughter Stephanie was hit by a car and killed while riding her bicycle through the intersection of Blanche and Matilija streets. Grief-stricken, Michael and Kay sold their house on Foothill Road and moved to Santa Barbara to get away from the bad memories.

But Parks had not soured on Ojai permanently. He was planning to move back one day, after building his dream house on the property he owned next door to the Chamblisses on McAndrew Road.

“It was the old Latvala junkyard and cow barn, which is still there,” Keith Nightingale says. “He built this sort of elaborate stone wall, and camped inside the cow barn for awhile.”

“His plan was definitely to live in the East End and develop this property,” Michael Chambliss says.

Woody and Erika discouraged this plan. They didn’t want all the Michael-and-Kay drama right next door to them. Money also was an issue, since Parks wasn’t working much, and rarely saved anything when he did work. The upshot was that he never built a house on the property, which was sold in 1977 when he and Kay divorced. But Parks continued to come to Ojai regularly to visit Woody and Erika. The last time Michael Chambliss remembers seeing him was at Woody’s funeral in 1981, at the Thacher School’s outdoor chapel.

By this point, Parks was working again in Hollywood, usually in supporting roles. No longer choosy about his parts, he pretty much accepted every job that came along and did his best with it. The Internet Movie Database lists 107 acting credits for Parks from 1973 to 2016, mostly TV guest-star gigs (“Fantasy Island,” “Murder She Wrote”) and supporting roles in forgettable films. Twice, he landed a recurring role on a high-profile series, only to see it cancelled when the season ended. One was “The Colbys,” a much-ballyhooed “Dynasty” spin-off that came and went quickly the mid-1980s. The other was “Twin Peaks.”

Parks was hired to play Jean Renault, the murderous French-Canadian gangster who looms large in the show’s second season (1990-91).

“I was a huge ‘Then Came Bronson’ fan, so I was eager to meet him,” says Mark Frost, who co-wrote the groundbreaking series with director David Lynch. (Frost now makes his home in Ojai.)

“He had an aura of danger around him,” Frost says, but also “a kind of battered dignity,” reminiscent of the tough-but-honorable heroes of detective novels by Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. “He was kind of mysterious and kind of sad. And that’s part of what made him so mesmerizing to watch.”

“Twin Peaks” was cancelled in 1991, but Frost hired Parks to play another memorable villain in the 1992 film “Storyville.” It was set in New Orleans, where Parks was living at the time.

“I couldn’t wait to work with him again,” says Frost, who wrote and directed the film. Unlike some of Parks’ previous directors, Frost was open to letting Parks interpret the character.

“He didn’t have a lick of vanity about him. What he did have was an amazing ability to give you what you wanted — even if you didn’t know that’s what you wanted — and complete it on the first take.”

Parks’ other fans included Quentin Tarantino, who created a small part for him in “From Dusk Till Dawn,” a 1996 film written by Tarantino and directed by Richard Rodriguez. George Clooney was the star, but Parks was so memorable as Texas Ranger Earl McGraw that Tarantino wrote the character into several films he directed himself, including “Kill Bill Vol. 1.”

“Tarantino basically saved him,” Nightingale says. “That brought him back from the abyss.”

After years of obscurity, Parks now had a cult following. The parts were still small, for the most part, but his reputation was growing again. He had cachet again. It was cool, in movie-geek circles, to reveal that you were a Parks aficionado. Reviewers now routinely singled him out for praise, even when they panned the films he was in.

His comeback seemed complete in 2011 when he starred as a scary fundamentalist preacher in “Red State,” a horror film directed by Kevin Smith, who wrote the part with Parks in mind. If Smith had sold the film to a major distributor, Parks might well have been nominated for a best-actor Oscar. Instead, Smith – with Parks’ enthusiastic support – chose to distribute the film himself, with predictable results. For Parks, it was another succes d’estime that failed to click at the box office.

Still, he kept working. And working. He never stopped, all through his 70s, right up until he died at home in Los Angeles on May 9. Mysteriously, the cause of death has never been made public. An old friend from El Camino College who attended his funeral said she was told he died of injuries sustained in a fall down a flight of stairs.

Reportedly, he was buried at sea, per his request.

Nightingale talked with him on the phone only two weeks before he died. The two men had kept in touch through the years, and Parks would visit Ojai periodically to have lunch with Keith and his wife, Vicki.

“He’d just drive up,” Nightingale says. “He loved Ojai.”

The Nightingales live near Parks’ former East End property, on which a subsequent owner has built a house atop the stone wall Parks had put up decades earlier.

“He was a dreamer,” Nightingale says. “Michael always had vast projects that he was going to do. It came down to money, which he didn’t have.”

He would have had plenty of money if he had let Lew Wasserman make him a star. Could he really have been another James Dean? Mark Frost says yes.

“I always thought he was the better actor,” Frost says.

But as an actor, Parks was an immensely talented artist in a medium that requires the cooperation of many other people, most of whom have their own ideas. He was frustrated, Dee Volz says, by his vision of a better world in which he could accomplish great things, “if only other people would change.”

“He was not at home in this world,” she says. “Some people are not.”

I absolutely adore Michael Parks. He was truly a beautiful man with a beautiful soul. He was a great actor and a wonderful singer. He worked so hard throughout his whole life. I also love the house he designed. It was exquisite. I wish he had been given the credit for his brilliant work but he will not be forgotten 💕

I went to school with Stephanie and Patricia. Stephanie’s death was tragic. First loss I ever experienced but was shocked to see Patricia at school the next day. We were kids, she needed to be around her friends… so sad. As long as I knew them, I never met their step dad.

Thanks for this article. I got to meet Michael at a Fan Fest in Parsippany NJ. about a year before he passed. He was in New York to be close to doctors and his daughter. I had been a fan ever since Then Came Bronson. He was wonderful to talk to. Over the years I had met several people who had worked on Then Came Bronson, so we had some things and people in common to talk about. His daughter saw how were getting along and talked to me for a while after my brief visit with Michael. (there were people in line to meet him after all) . Also I had talked to Michael over the phone a couple times before via the Two Wheel Power Hour radio show which my friend Larry Ward hosted. Everyone who met and worked with Michael (on the crews) loved him. (Producers and Directors maybe not so much).. While I was at the Fan Fest, his wife Oriana took a picture of us which I treasure. I will try to out a couple links to a tribute video that I took on the day Michael passed, and to the picture of us together.. This is a link to the picture of Michael and me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10216537324894211&set=t.1490954183&type=3 And this is the link to my tribute to Michael on the day he passed. I hope these can be included in the post. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UI5kMVODIK4

Hi, my name is Brigette LaVigne and my best friend at this time was Patricia parks. I was at the Park’s house a lot in ’68-’69. When Stephanie was run over by a car, mangled and nearly decapitated, my mother, Barbara was summoned to identify her body. My mother was a teacher at St. Thomas Aquinas in Ojai. My mother was horrified at the sight of Stephanie. It was surreal to see this little girl with her head nearly off and dead. This tortured my mother for years. Seeing that…