FEATURE | By Nao Braverman

Allies for Ojai’s Watershed

Watershed Progressive’s Michele Cabrera, joe madden and Aja Bulla Richards. Fancy Free Photography

Brandi Crockett

The issue of our falling water table is so overwhelming it nearly paralyzes me. The two water districts that serve the City of Ojai, supplying water to a total of approximately 69,000 customers including some in Ventura and the Rincon Beach area are sourced by Lake Casitas, and groundwater alone. Lake Casitas is at 35 percent of its 238,000 acre-foot capacity as of January 12th. The groundwater, which is Ojai’s primary water source, is in danger of depletion.

I am not alone. Everywhere I go Ojai people are talking about drought. When we get even a drizzle there’s collective rejoicing to be heard in the coffee shops and grocery lines, and the farmers markets. So what can be done?

A locally based organization, Watershed Progressive, has answers. Their intent is to connect California communities with our watersheds, ultimately giving us tools to recharge groundwater, conserve what rain we get when it comes, and use that water responsibly.

“Ojai does have enough water,” Regina Hirsch, founder and executive director at Watershed Progressive assures me. But in order to continue to thrive here, the way we manage water has to change.

In the city of Ojai alone, if all residents changed their water use by reducing their demands and using water-saving solutions, like gray water (domestic waste water from laundry, bathing and food prep) we could conserve 182 acre feet,” said Hirsch. “That’s just residents!”

The average American family uses more than 300 gallons of water per day at home, according to the EPA. Most Ojai residents are making an effort to use less. But there are a lot of surprisingly easy and low cost changes that could help us conserve even more, according to Hirsch. While conservation is an important component of the organizations work, they are focused on not just water itself, but the land surrounding water at its source, the watershed.

“Water is part of our everyday life but it also connects us with multiple ecosystems, distant communities, other species” explains Aja Bulla-Richards, creative director of Watershed Progressive. She pauses during our interview, when a little bird in a tree catches her attention. With multiple degrees in architecture and a lifelong dedication to environmental issues, she has come to focus on water infrastructure, and watershed, leading up to her work with Watershed Progressive. “I’m interested in how can we design our homes and our cities differently so we really understand that we are part of that cycle, and also design the places we live to be more resilient.” Resilience for our community means drought resilience, soil fertility, fire prevention, and more.

For my family, the easiest change we can make is in our backyard. On a crisp fall morning, a small team of landscape architects and water resource experts from Watershed Progressive ring my doorbell to make a professional site assessment.

Nicole Stern, a Watershed Progressive landscape architect, also a mother, notes my non-native milkweed, apparently poisonous. Good to know, I will be moving that out of reach of my three year old. But more importantly, the lawn of weeds that covers most of the backyard and still gets irrigated twice weekly must go. We are in agreement on this.

She gives me a plant palette for Ventura County; labeled illustrations of shrubs, trees and wildflowers, sage greens, purples and yellows, golden yarrow, California lilac, deergrass, creeping sage. The soft hues are of plants that are meant to be here, and use very little water. There is also a spread of native plants that require moderate irrigation, but I’ll get to that later. For now, I want to erase the image of our suburban boxed-in backyard, and visualize a small piece of Mediterranean wilderness in its place, and to lower our water bill while we’re at it.

Joe Madden, water resource project manager for Watershed Progressive trudges through our mowed weeds and haphazard array of potted plants in his heavy boots and brown felt hat, surveying the laundry room, the location of bathrooms, taking notes on a clipboard.

He describes a system that we could install to use grey water from our showers to irrigate plants in the backyard. Another grey water system called “laundry to landscape” could reuse wastewater from the washing machine to irrigate our front yard landscape, particularly an old redwood, which is neither native nor drought resistant, but too precious not to keep. “Aside from a little drip irrigation to water vegetables, you could reduce your irrigation water use to almost zero,” says Bulla-Richards.

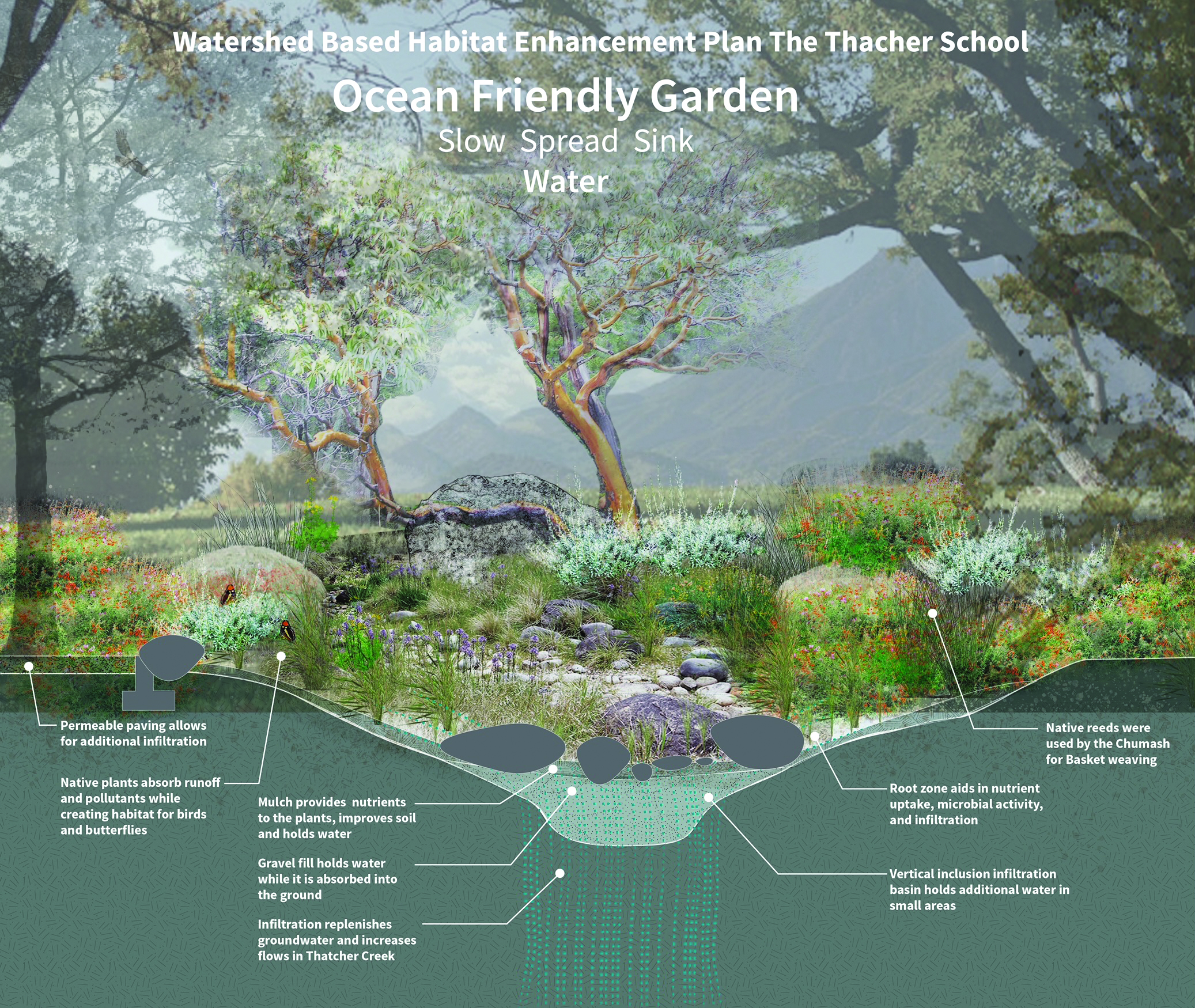

An ocean-friendly garden diagram

When I hear gray water, I imagine transporting a bucket of soapy suds from my shower to the garden. So this technology, which will require no more work than an automatic sprinkler system, is good news. Gray water can also be used to irrigate the native fruit trees, medium water-use native plants mentioned earlier. To be water resilient doesn’t mean that we can’t plant the fig, persimmon, and orange trees I want, according to Stern. We would just have to irrigate them with the used water from our showers and laundry, which, with a family of four is not a small amount. I tell Madden the number of loads of laundry we do each week (at least 3) and the number of showers, which he notes on his clipboard.

This site visit is part of a collaborative program, the Land Resilience Partnership, between Watershed Progressive and state and county agencies (California’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, the California Office of Resource Bonds, California Department of Water Resources, Ventura County Resource Conservation District, the City of Ojai and the Ventura River Water District). Bringing together multiple agencies and government entities, the partnership fosters collaboration on this very precious goal of improving our watershed.

The Land Resilience Partnership started up in Tuolumne County in Northern California, along with Watershed Progressive in its early years, where it was a huge success. There, they were doing assessments, technical assistance, designing and building systems for water reuse. Based on that idea, the organization started a similar partnership in Ventura County.

The site visit to my home in particular was made possible by a partnership with the Ventura River Water District, the water utility that serves the Ojai neighborhood where I live.

By facilitating work on sites like mine, the water district can help reduce consumptive use of water with many small actions that add up to a significant amount of water to be left in streams and aquifers, explains Madden.

Almost all that they do, at Watershed Progressive, revolves around other partners, says Hirsch. It’s all about collaboration. As an organization they are constantly exchanging ideas, improvising, trying out new solutions.

“The idea is not just to design something that sits on paper. It’s really to engage people in trying things in their own backyard,” said Hirsch.”

The landscaping of homes, backyards, and small parcels is just one function of the organization. They also have a handful of larger projects under their belt, including those at Thacher School, Besant Hill School, the Ojai Valley Inn, and the City of Ojai.

At the expansive and scenic campus of Besant Hill School, they designed and proposed a system of rainwater collection from the roofs of buildings, and a large storm-water retention basin to store water from seasonal rain that the school can dip into during the dry summer season, and frequent droughts.

“As a result of climate change we may be experiencing less rain, but when the rain comes we can expect more dramatic rain events,” says Bulla-Richards. The water collection tanks and natural landscape features can be used to collect and store that water for the future.

At Besant Hill School, for example, they proposed the restoration of oak woodlands, which provides habitat for a number of native wildlife species. The restoration of habitat in turn improves the health of our rivers, lakes, ponds, and the surrounding wildlife. Some of this restoration work has been installed with Watershed Progressive staff, local volunteers and Besant Hill students.

The Ojai Valley and Ventura watershed, for a variety of factors, is a good location for the organization to focus on, explains Bulla-Richards, who was born and raised in Ojai. “We have a diverse geographical landscape on a small scale, and the need for water conservation. The Ventura Watershed is now becoming a model for strategies that build land and water resilience for future generations.”

But Watershed Progressive’s projects span across the state. Hirsch’s watershed work began in Morro Bay, at the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Board. There, she worked on different water use solutions. She then moved to Tuolumne County and opened a plant nursery café called Mountain Sage, where the seed for Watershed Progressive was born. The nursery also functions as an event-center, hosting talks and other educational gatherings, bringing together members of the community. It’s become a hub for learning, and discussion, a place where people can exchange ideas about water conservation and environmental restoration, among other topics. It was there that Hirsch developed a contracting arm, which allowed the organization to design and install water reuse systems.

Not far from the nursery is one of the organization’s early water reuse projects at Yosemite’s Evergreen Lodge, where a gray water system to this day recycles 1.9 million gallons of water annually from guest cabins, staff housing and laundry. A subsequent project at the nearby Rush Creek Lodge reuses over 3.3 million gallons of gray water annually.

In and around Yosemite National Park, there is more rainwater to reuse. But with Ojai’s climate, the need for conservation is immediate and dire. When Watershed Progressive was invited to expand their work to the Ojai Valley, they readily accepted.

“We found, with coastal watersheds, that were more shallow we could understand the hydrology better than in the complex environment of the Sierras” said Hirsch. “In this location we can get a better idea of how these solutions would help not only people where they live, work, and play, but also improve the health of our watersheds and create opportunities for people to connect to the natural world around them.”

With the help of partnerships, the organization already has its hand in a number of watershed improvement efforts in the Ojai Valley and throughout the county. They’ve opened a small office in downtown Ojai and are here to stay. What remains is the future. With a long list of local projects, the organization needs workers. In the summer of 2022 they will be expanding their training and mentorship program to a Ventura branch.

Dubbed the Headwaters Initiative, the program provides youth with pathways toward careers in watershed resilience, conservation and restoration. Participants will gain a variety of skills, including, but not limited to, gray water design and installation, rainwater harvesting, graphic design and other tasks connected to watershed transformation. Following completion of the program, they will have an opportunity to be hired by Watershed Progressive. While this will help the organization expand, it also has the added benefit of educating future generations about watershed improvement, training more professionals in water reuse technology and increasing local jobs. (for more information, visit www.watershedprogressive.com/headwaters-initiative).

Educating future generations, the Watershed Progressive team also hopes to foster a change in mindset regarding our relationship with natural systems and other species.

To this end, the organization is a partner in the Green Valley Project, a youth leadership in restoration program led by CREW. This spring, Watershed Progressive will support the local youth council in designing and planting pollinator corridors around the Ojai Valley.

Trends in residential landscaping are shifting away from highly irrigated lawns, imported plants and manicured bushes. Perhaps we can take that further and replace the traditional suburban residential landscapes with the wild beauty of native plants and flowers, butterflies, hummingbirds and the occasional heron. Patch by patch, we can transform our lawns and backyards into thriving, interconnected native habitats and vibrant ecosystems that will sustain our future here. The practices used to save water in homes can simultaneously create healthy soils and vegetation, ultimately providing shade and fire resilience, and benefitting wildlife for years to come.

Watershed Progressive hopes to make Ojai an example of what is possible when a community, even one as perilously dry as ours, comes together and really cares for their land and watershed.

To have a site visit and consultation, sign up at watertoolkit.org.

Leave A Comment