Chariots of Fair

Pioneering Sheriff Goes All Out, Off the Track, and On

By Patricia Clark Doerner

Tom Clark, Ventura County Supervisor and champion chariot racer.

Thomas Scribner Clark was born October 18, 1865 to Michael Hugh and Margaret Lynch Clark in Lafayette, Wisconsin; the first state west of the Alleghenies to be settled by immigrants. He, his mother and six siblings arrived in the Ojai Valley in 1881 after being sent for by their father, Michael Hugh.

Michael had commuted back and forth from Wisconsin to the Ojai since 1868, the year his brother, Old Tom Clark, settled in the Upper Ojai. On his arrival, “red-haired Tommy” convinced the local stage line that he, at 16 years of age, was capable of driving stage for the handsome sum of $30 per month. Before long, he was considered the only driver capable of delivering passengers to Ventura during the valley’s periodic torrential rain storms.

He risked his life not once but many times. Like Kit Carson and the Pony Express, Tom got through. The mail must go through at any cost.

Tom battled through the rains and old-time stick roads, forded or swam flooded, roaring creeks; he raced and smothered through forest fires. Like Kit Carson and the Pony Express, Tom got through with the mail. “When other routes failed and the beach road was the fastest, Tom took that route and breasted the treacherous ocean tides. Often soaking wet for hours, he must continue his ride from Ventura to Santa Barbara and back to the Ojai, a hard journey and one apt to give him death from exposure.” (undated article)

Eighteen-ninety-four was a big year for Tom. Not only did he and brother Will open the Clark Brothers Stage Line (at the present location of Village Drug Store), charging $1 for trips between Nordhoff and Ventura with the additional charge of 50 cents for one trunk and $1 for each additional trunk. It was also the year that he married Miss Ella Backman. He built their home directly behind the Clark Brothers Stage Line at what is now the rock enclosed parking lot behind Ojai Rexall.

May 1903 was the month and year that Tom and his Nordhoff Livery initiated a stage line between the Ojai Valley and Santa Barbara with a six-horse team and six-hour round trips twice/week. His many tales of bravery were listed in the local papers and served to build his reputation as a brave man in times of need and a responsible business man. It was a proud moment when he, the son of Irish famine immigrants, was asked to serve as a founding member of the Committee of Fifteen, “pledged to enforce the law, preserve order and promote good citizenship” in the valley.

On Nov. 8, 1904, Tom was elected to serve as Ventura County Supervisor for the 3rd District. He fought continually for good roads between the Ojai Valley and Ventura and through the Maricopa Road to Bakersfield. His obituary stated: “Tom has a passion for good roads — he knew all the bad spots. After he was elected Supervisor and put in charge of Roads and Bridges, he acquired road equipment piece by piece (none had been owned by the county before).

Tom’s great goal: a dry road from Ventura to Ojai. In 1915, he was instrumental in putting over the $1 million bond issue which eventuated in the fine highway from Ventura to Ojai and the paving of Main Street (Ventura).

According to A.F. Knudson, Engineer, “The Maricopa tri-county road project would never have been completed had he wavered … it was the great work of his lifetime.” He was also responsible for Foothill Road, Wiggley (Gorham) Road, Rincon Road, the Ventura River Bridge, and the State Highway. At one time, the Santa Ana Road was washed out by a flood. The original estimate for rebuilding ran to $80,000. Mr. Clark was positive that $20,000 was sufficient to do the work. So certain was he that he told the other county board members that if a bid that low was not forthcoming he would pay out of his own pocket the cost of advertising for bids. The bid that took the job was $19,992.50 (The Ojai, Aug. 9, 1940). He improved all roads in the valley and built the new roads over the grade and along the creek. He was the prime inspiration for the building of the Maricopa Road and the reconstruction of Casitas Pass.

During the Depression, Tom bought a rock crusher with WPA dollars and leveled a rock wall 5’ high and 8” wide — solid rock — and hired men to build Gorham Road and the road by the Pizza Hut (now Boccali’s).

Tom Clark’s performance was given to thousands of visitors not for any particular gain for himself, but entirely because of his interest and devotion to good, clean sport and to the Fair.

and the oil fields almost shut down, men kept living leaner and cheaper until finally lots of families got down to plain nothing? Some were starving. Many of these thronged the courthouse. They were desperate. Something had to be done. Something was done. The Board of Supervisors agreed to appropriate thousands of dollars of tax money for people in this sad situation. The question came up: “How are we going to pay out this money? Shall we hand it out or shall we pay it out as wages.” It was thought the men had rather work for it. They might be insulted at what looked like charity. Then one supervisor from the other side of the county rose up and said, “Well it IS charity. Give them a dollar-a-day wages, that is enough for them.

Did Mr. Clark agree to that? No. He was on his feet like a shot. “No, gentlemen. We hope this state of affairs will not last long, but if these boys are going to work for this money, we must pay them at least two dollars a day or it will bring down the wage scale of other workers too low.”

Yes, he got $2 a day for the men when they needed it most and the men of this district should come across for him when he needs it most, if they want to be true men. When that appropriation was used up, the board had to ask for more as conditions were even worse. Tom had his roads and streets in good condition. There wasn’t really enough work to go around. Did some of the boys lean on their hoe handles? Of course they did, but Tom Clark is sensitive and high-minded. He tries to treat the other fellow as he wants to be treated. He tried to give his men work instead of offering them a hand-out when they were down-and-out through no fault of their own.

Did you know that in the old days here the county road scale of wages was $1.50 to $2 per day? Who raised that sum to $3.50? Tom Clark. After the World War all other wages were up and living was high. There was a big fight on the board of supervisors about raising county wages. Tom Clark won. He said “Gentlemen, I am going to pay the men in my district $3.50 and you do what you please in yours. The others then raised as high as $3 and paid that for a long time when Tom was paying $3.50 to his men. (From the Minutes of the County Clerk.)

As the years passed, Tom invested in horses of his own and a stable and kept carrying mail. When he became full-fledged owner of a livery stable (now the Village Drug Store) he ran for Ventura County Supervisor. For many years this job as supervisor paid only on the days the board met. The county was so small these meetings were few except in the month of July when the tax question arose and must be settled.

The devastating fire of 1917 gives another instance of Clark’s bravery. As Henry Sparks of The Avenue reported:

At the moment I cannot recall any conflagration in this county that was threatening the complete destruction of a community as was the Ojai fire in June 1917. At two o’clock that afternoon a brush fire started several miles west of Wheeler’s Hot Springs in the Matilija. A strong hot, drying wind was blowing from the northwest at the time.

L.R. Orton continued: Hundreds of automobiles from Ventura loaded with volunteers rushed to Ojai to assist the residents of the stricken city that night. When Supervisor Tom Clark got up there from his duties at the courthouse, he found the rescue work badly handicapped for lack of water pressure. One of his first acts was to select the most exposed section where the fire could gain the greatest headway and organized a bucket brigade.

He sent for all the wash tubs the town could muster. One of these was set under every available hydrant. From these pails, the bucket brigade was formed. He next ordered barley sacks and designated certain dependable men to mount the houses with shingled roofs to beat out any blaze there.

Tom now turned his attention to the Foothills Hotel and several homes in the northern outskirts of town. As Tom and his men arrived at the closed hotel, the caretaker refused to let them have a ladder with which to mount the roof. Thwarted in gaining access to this hostelry, Tom and his crew ran to the beautiful residence of C.M. Pratt and was given assistance to get on the roof with his helpers; they saved this valuable structure. He did this for several other cheaper homes, on one of which the roof was so hot that his face was blistered.

Always wiry and tough, Tom continued to fight fire in the business section throughout most of the night. In the meantime Big Bob and the rest of the Clark family, including the women, were out fighting the flames to save homes between the town and the Thacher School, for the left wing of the fire was sweeping along the base of the mountain range paralleling what is now Grand Avenue.

Is it any wonder that the entire Clark family is highly regarded in the Ojai valley and throughout the entire county?

But it wasn’t all work for Tom Clark or the other Supervisors. The May 26, 1916 edition of The Ojai reported: “Chairman Clark of the Board of Supervisors was kidnapped by his official associates, Sunday, and whirled away to Redding, where the State convention of Supervisors is in session this week. The county car was driven up early to convey him to Ventura to join the party, but he turned it back empty, owing to press of business deciding to forego the trip. But the chairman was an important factor, and when his intention to shy the trip became known, Supervisor Roussey, with County Clerk McGloskey

Articles proliferate concerning his generosity during Depression years: “Did you know that a few years ago, before there was any Federal relief, when everything went smash into custody, in spite of his protests.”

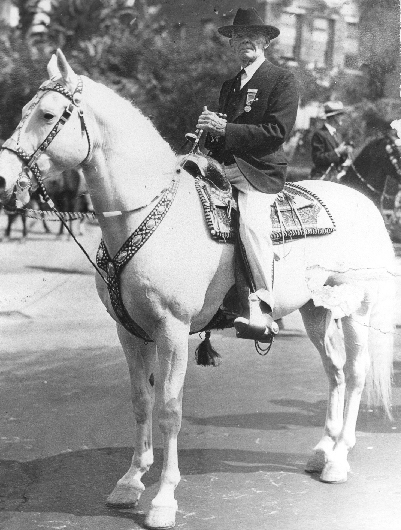

By 1936, Tom and fellow County Supervisor Adolfo Camarillo had formed a close friendship; in October of 1936, they are pictured riding the famous pure-bred Camarillo white horses leading the parade “Marking the Bay Bridge Opening.” (October 29, 1936)

But whatever Tom Clark’s accomplishments in the political field, none can match his accomplishments in the arena at the Ventura Fair Ground. As a member of the Ventura County Fair Board, Tom suggested that Chariot Races be introduced as an attraction after said races were abandoned by the Rose Bowl as too dangerous. Tom, himself, was happy to drive year after year, breaking the world record for four-abreast chariot racing in 1926, an event notable enough to be mentioned in the Boston Globe, or, as reported by The Ojai, “the garl- darndest, air-splittingest, blood-curdlingest chariot races ever staged on the Pacific Coast.” After the death in 1918 of Joe Donlon, his most formidable opponent, no one seemed able to beat the “mighty dynamo” from Ojai.

Bob Anderson, the Flying A hands from Santa Barbara, Happy Jack Hawn, Gene Kennedy, Lieutenant Rockwell, and Captain Joe Rogers regularly went down to defeat. Roy Rogers he beat by three lengths. Tom Mix refused to race unless he were given some assurance of winning; he had his fans to consider. Tom Conrad gives us his grandfather’s answer to that one: “I’ve got my own fans to consider, too — all those kids out there.”

The story continues that Mix did return to race another day, the agreement being that he and Clark switch teams. They did. Clark won.

How did he do it? In the first place, he used either wild horses or horses not broken to harness. Secondly, he just knew how to drive, as one old racetrack man put it. Whatever, it was spectacle at its best.

Tom’s niece, Clare Clark, remembered climbing up on the whitewashed rail enclosing the half-mile track to wait — and wait for the race to begin (the task of harnessing four wild horses to a chariot, Roman or otherwise, is neither simple nor quickly done — then, the thrill — the rush of wind — the very earth moving underfoot as the “modern Romans” thunder past. It was literally a thrill per second; in 1915, the first year of the race, the winning time was 58 seconds.

By 1920, “the sorrel-topped Roman of the Ojai” was wearing a Roman toga and “issuing challenges to Bill Hart, Tom Mix or someone in Mix’s class.” The Ojai announced that Cecil B. De Mille and Tom Mix were both answering the challenge and in 1921 Mix did arrive to compete in the chariot races. “”TOM MIX WOULD NOT RACE WITH TOM CLARK, WINS FROM BOB ANDERSON INSTEAD.”

Tom Mix has lost out as an idol in these parts. It is because he backed down in his alleged agreement to race Tom Clark yesterday afternoon. Instead he used Clark’s chariot and won in a race with Bob Anderson.

Cliff Burrell managed to give Clark a run for his money in 1926, winning the first race of the fair (Clark “got off to a bad start” reported the ever-loyal The Ojai). Clark then returned the favor, beating Burrell in in the final race of the fair with a time of 52 seconds. In doing so, he set a new world record for four abreast chariot racing.

Why did he do it? The Ventura Free Press, as quoted in The Ojai (Oct. 1, 1928) gave one answer:

“Tom Clark’s performance was given to the thousands of visitors not for any particular gain for himself, but entirely because of his interest and devotion to good clean sport and to the fair. He won the small purse offered for this race but he will be out far more than this in the expenses of the feature. He contributed to the enjoyment of thousands and his ‘act’ proved one of the great features of the fair.”

The Ojai, reporting on the “Educational Exhibit” of the Fair (Oct. 12, 1923) had an answer closer to the heart:

“In this department was a reminder of childish hero-worship that should cause Supervisor Clark’s heart to flutter just a trifle. Cut from white paper is a horse, a chariot, and the figure of a man, and in white letters the name, ‘Tom Clark,’ the whole mounted on a black background. It tells of admiration for the veteran charioteer of many triumphs, even if it does not thrill like the race and the man so well remembered by the child artist.”

The “veteran charioteer” drove his last chariot race in 1930; he was 65 years of age, winner and still champion.

Editor Kilbourne of The Ojai wrote of Tom on his death Aug. 4, 1940, “He was that dearly prized and rare man, a public official whose honesty never was questioned; he served without thought of personal gain or advancement.”

Leave A Comment