Feature | By Mark Lewis

Going the Distance

Ojai is a long way from the big-city boxing rings where world championships are decided. But once upon a time, champions and contenders regularly would trek out here to the boondocks to tune up for their next bout at Pop Soper’s rustic training camp along the Ventura River. It all started in the spring of 1927, when the most famous man in America came to Ojai seeking redemption.

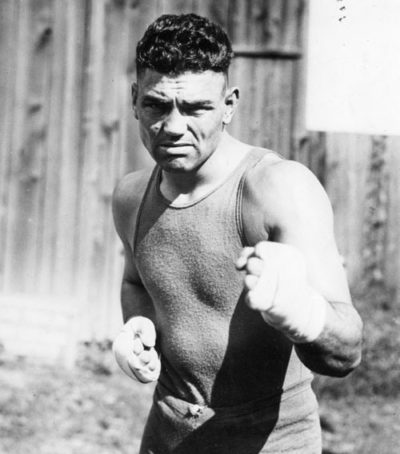

Jack Dempsey sought redemption for a tough loss at Pop Soper’s Camp above Ojai.

Ranger Bill Burris was driving north toward Wheeler Hot Springs on the brand-new Maricopa Highway to investigate reports that the recent heavy rains had damaged a perched bridge over a creek in the National Forest. Along the way, he encountered an unexpected sight: a big man jogging along the highway pushing a wheelbarrow in which a smaller man sat upon a pile of rocks.

“And I thought, ‘What are those crazy guys up to?’ ” Burris recalled years later. “So I drove up there slowly and parked on the other side and walked back and introduced myself, Forest Service, and the man said, ‘I’m Jack Dempsey and this is my manager, Wilson, and for exercise we were building up that perch.’ ”

It was April 1927, and Dempsey, “the Manassa Mauler,” was the greatest hero of America’s so-called Golden Age of Sports. After winning the heavyweight crown in 1919, Dempsey inaugurated the new era in 1921 when he defended his title against Georges Carpentier in front of 91,000 spectators, who paid a combined $1.7 million to see the fight – boxing’s first million-dollar gate. Another 400,000 people tuned in on their newfangled radio sets to hear history’s first live sports broadcast, and millions more read about the fight in newspaper columns written by the likes of Grantland Rice and Damon Runyon, master wordsmiths whose prose turned Dempsey and his peers into legends.

Not that he had many peers. Babe Ruth and Red Grange were national heroes too, but they played team sports, baseball and football. Dempsey stood alone when he fought, like a Roman gladiator fighting for his life in the arena. Every title defense was a huge national event. After knocking Carpentier out, Dempsey next took on the powerful Argentine contender Luis Firpo, “the Wild Bull of the Pampas,” who punched the champ clear out of the ring in the first round. Dempsey climbed back in and knocked Firpo out in the next round to retain his title, and create another touchstone memory for the Jazz Age.

“More than any other individual, Jack Dempsey created big-time sports in America,” noted sportswriter Roger Kahn wrote in his book “A Flame of Pure Fire: Jack Dempsey and the Roaring ‘20s.” “Dempsey was more prominent that any of his great sporting contemporaries — Bill Tilden, Red Grange, Bobby Jones, Babe Ruth.”

But in 1926, out of shape after a long layoff, Dempsey was out-boxed by Gene Tunney and lost his title by unanimous decision. “Honey, I forgot to duck,” Dempsey explained to his wife, a line Ronald Reagan would repeat to his own wife 55 years later after being shot by a would-be assassin.

Dempsey retreated to his Los Angeles home to lick his wounds and ponder his future. At first, he rejected the idea of a rematch with Tunney.

“I was beat like no man should be beat,” Dempsey recalled years later. “I just didn’t think I had enough left in my legs to catch a real boxer anymore. And I had doubts about what I could do if I did catch him.”

To find out whether he still had what it took, Dempsey decided to set up a training camp in an out-of-the-way location, far from the distractions of Hollywood — and far from his wife, movie actress Estelle Taylor, who disapproved of boxing. He reunited with his old trainer Gus Wilson, and they came to Ojai together to check out Wheeler Hot Springs, where the flyweight champion Fidel LaBarba had trained in 1925. But Wheeler was a fairly large resort, with distractions of its own. Instead, Dempsey cast his eye on a much smaller resort called Soper’s Ranch, located near the mouth of Matilija Canyon, at the point where the two forks of Matilija Creek converge to form the Ventura River.

The proprietor, Clarence Anthony “Pop” Soper, was an Ojai native, born on the family ranch in 1881. His parents, Philander and Sarah Soper, had homesteaded the property in 1874, at a time when tourists were beating a path to the Ojai Valley to visit the new hot springs resorts in Matilija Canyon. Clarence left the valley as a young man to work for Wells Fargo Express — a railroad job, essentially. But about a decade later, he fell ill, and his doctors told him there was no hope.

“I came back to Matilija to die,” Soper told an interviewer years later. “But when it seemed like my time was not as close to being up as the doctors estimated, I packed up some grub and camping gear and took off for the back country, where I stayed for a year without seeing another living soul.”

Finally deciding that the doctors had been wrong, Soper packed back up and returned to civilization: “When I came back I felt fine and took a job as [assistant] manager at Wheeler Hot Springs for three years before buying the 700-acre ranch from my father’s estate.”

Despite having no hot springs on his property, around 1920 Pop put up a cluster of cabins just west of the river and opened his own resort, which with stunning originality he called Soper’s Ranch. He was the smallest player among the area’s spring-fed resorts, but evidently that was just what brought Dempsey and Wilson to his door seven years later. Here was a place they could take over and reshape as they saw fit. Soper was happy to go along with the transformation, after Dempsey pointed out how much money Pop could make selling tickets and beer and food to the many spectators who would come to watch the ex-champ spar in the ring.

“His manager said that Jack wanted a place to train where he could feel at home,” Soper said. “So I fixed some quarters for him and then built the fight ring in which he trained for 96 days in preparation for the contest with Tunney.”

Initially, Dempsey had no fight to train for; he was just testing himself, trying to get back in shape. A few weeks of pushing wheelbarrows and chopping down trees at Pop Soper’s place gave him the answer.

“My workouts here have convinced me that I can get back into real fighting form,” he informed the press on April 28.

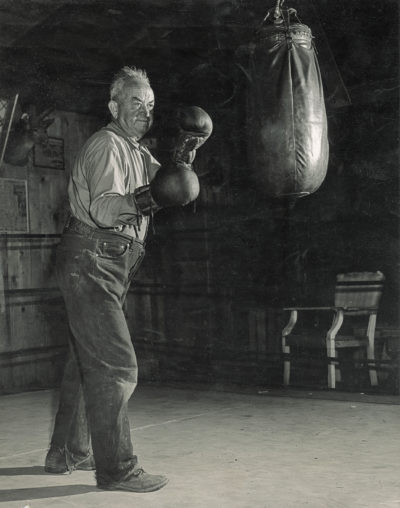

Pop Soper trained several generations of top boxing talent at his ranch.

“Soper’s Ranch” became a frequent dateline in the national press that spring, as reporters flocked to the little Ojai resort to receive updates from Dempsey’s camp about the negotiations for a rematch with Tunney. As Dempsey had predicted, thousands of fight fans flocked there too, providing large audiences when he worked in the ring with his sparring partners. (Among these visitors was the Chicago crime lord Al Capone, a big Dempsey fan.)

But it was not Gene Tunney whom Dempsey was training for; it was Jack Sharkey, another top heavyweight contender. Boxing promoter Tex Rickard had decreed that Dempsey and Sharkey should meet in an elimination round, with the winner earning a shot at Tunney for the title. And so, after three months at Soper’s Ranch, Dempsey headed east to meet Sharkey in Yankee Stadium in front of 85,000 spectators. Sharkey, a future champion, was well ahead on points in the seventh round when Dempsey stopped him cold with a devastating left hook.

Two months later, he met Tunney in Chicago’s Soldier Field before 105,000 fans, while millions more listened to the radio broadcast. Once again, Dempsey entered the seventh round trailing badly on points, and once again he dropped his opponent with a left hook, part of a devastating seven-punch combination that seemed to have ended the fight. But then Dempsey stood over Tunney instead of going to a neutral corner as required by the rules. The referee delayed the count until Dempsey finally walked away, giving Tunney an estimated 14 seconds to recover from Dempsey’s onslaught and get back on his feet. Did the extra four seconds make a difference? Fight fans have been debating that question for 91 years, but there is no answer. All we know is that Tunney won the famous “Long Count Fight” by unanimous decision to retain the title.

Dempsey announced his retirement, but few believed him.

“Dempsey Launches Comeback Campaign,” the Los Angeles Times blared in March 1928. “Jack Orders Camp Alterations/Ex-Champion Plans Extensive Improvements at Ojai/Former King to Fix Up Soper Ranch Training Quarters.”

The source for this story was none other than Pop Soper, who told the Times that Dempsey would start training there in April. If that really was Dempsey’s plan, he quickly changed his mind. “I’m through for all time,” he said, and he was as good as his word. The Tunney rematch turned out to be Dempsey’s swan song; he never fought again, except in exhibitions, and if he ever returned to Soper’s Ranch, history does not record it.

But other fighters did come to the Ojai Valley to train at Soper’s. Lots of them.

“Soper’s Ranch, one of the famous canyon resorts of Ojai, has been coming in for an unusual amount of visitation for even so popular a holiday center,” one Ventura County newspaper reported in October 1929. “The past week or two, since Mickey Walker, the world’s middleweight champion, established training quarters there for his approaching battle with Ace Hudkins in Los Angeles on Oct. 24. Fight fans from all over the county are making Soper’s their Mecca, and on the weekends, sportswriters, trainers, fashionable patrons of the arts fistic and just plain curiosity seekers have been flocking in by the car loads.”

In addition to Walker (who won that fight with Hudkins), other world champions who trained at Soper’s in the 1920s and ‘30s included the flyweight Fidel LaBarba (who had switched from Wheeler Hot Springs), the junior welterweight Mushy Callahan and the middleweight Ceferino Garcia, inventor of the bolo punch. Pop’s regular clients also included locally bred fighters such as the future Ventura County rancher A.E. “Bud” Sloan. Billed in the ring as Haystack Bud Sloan, he achieved national renown in the late ‘30s and early ‘40s for his patented ice tongs punch, which involved using both hands to simultaneously punch his opponent on both sides of the head.

“I was a young buck from a ranch,” Sloan would recall to an interviewer. “Pop took me under his wing, took to me like he was my dad.”

The facility where Sloan trained was not the one where Dempsey had trained. In 1932, Pop had moved his boxing operation east across the river to another part of his ranch, bordering on the highway. He built new cabins there to accommodate his boxing clientele, and eventually added a store, a gas station and a restaurant, which he decorated with boxing memorabilia and with his collection of mounted fish and stuffed reptiles, including a very large boa constrictor. Soper also collected coin-operated music boxes, player pianos and nickelodeons, which were on display.

His original camp, west of the river, went back to being a small, rustic resort for vacationers. Pop had married a widow from Santa Barbara, Jessie Catlett Kellogg, but they did not get along very well, so she lived at the original resort and managed it, while he lived at the relocated boxing camp. Even with a river between them, the couple still could not get along, and eventually Jessie moved away. (They had no children.) In 1939, Pop sold the original resort to Rick and Eugenia Everett, who renamed it Ojala and operated it for many years.

Pop continued to run the relocated boxing camp, where he endured the great flood of 1938, which washed away five of his cabins, and the great fire of 1948, during which firefighters used his camp as their headquarters. At one point, as the flames closed in, Pop was told to evacuate. He refused.

“I’ve been here a long time, and I’m going to stay right here,” he said, and continued to pump gas into the fire trucks.

The camp survived the fire and by 1954 was enjoying a revival, boosted by the frequent presence of Art “Golden Boy” Aragon, the most popular boxing attraction in Southern California.

“Old Pop Soper, who’s been around boxing as long as the glove, is currently enjoying a rebirth of big-league activity at his ancient little muscle resort in the Ojai hills,” Los Angeles Mirror columnist John Hall wrote. “It seems that a few fighters have rediscovered the fact that rugged country, fresh air, good food and hard work form the perfect combination for getting into peak shape.”

Soper was a familiar presence in the town of Ojai, where he often was seen driving his distinctive 1929 Packard convertible and letting local children ride in the rumble seat. They loved to visit his camp, although less for the boxing than for the other amusements Pop provided.

“I used to go up there on my horse when I was just a kid,” Dwayne Bower recalls. “We’d ride up and have lunch.”

Bower and his friends enjoyed putting nickels in Pop’s music machines, which did not necessarily make beautiful music together.

“Within the glass cases of these machines of yesteryear are mechanical contraptions which play violins, pound pianos, blow flutes, tinkle tambourines, ring bells, clash castanets and bang on xylophones to make a weird hodgepodge of sound,” The Ojai newspaper noted in a story about Soper’s 73rd birthday party in May 1954. Pop was a beloved local character, and his birthdays were community events. But he professed to be unimpressed with his status as an Ojai celebrity.

“I don’t give a damn, as long as I have a little money, three square meals a day and a good bed,” he told the newspaper.

He died in that bed three years later, at the age of 76. His younger brother Lennie tried to keep the camp going, but Lennie was a beekeeper by profession rather than a boxing camp operator, and Soper’s Ranch did not long outlive its creator. It

closed for good later in 1957, and most of its buildings were demolished in January 1963, inspiring area newspapers to run “end of an era” elegies.

“An old Quonset hut once used for storage, several deserted cabins and piles of splintered lumber are all that remain of the camp where once some of the greatest prizefighters in ring history trained,” one paper noted. “The gym and the ring have been dismantled and carted away. … A smashed jukebox stands bleakly by the roadside, and nearby is the stained and scuffed café counter where once sat boxing moguls with their fighters.”

That café counter is still propping up elbows at Cold Spring Tavern near Santa Barbara, where it serves as the bar. (The Tavern also boasts among its outbuildings the original Ojai Jail from 1874.) Pop’s 1929 Packard ended up in the hands of Dwayne Bower — his first car, and still today a prominent part of his “Ojai Vintage Vehicles” collection. The car was the star of the Ojai Valley Museum’s 1995 history exhibit devoted to Soper’s legendary training camp, which was the first exhibit the museum mounted after moving into its present home in the former St. Thomas Aquinas Chapel. The exhibit noted that about 550 boxers trained at Soper’s Ranch from 1927 to 1957, including several world champions and one genuine legend: Jack Dempsey.

The last remaining cabins from Soper’s roadside training camp survived in obscurity until last December, when the Thomas Fire destroyed them. The fire also swept through nearby Ojala, on the other side of the river, and destroyed most of its structures, possibly including the one where Dempsey stayed in the spring of 1927, when he came to the Ojai Valley seeking answers to certain questions he had about himself. He found those answers here, and even though he never regained his title, and lost most of his prize-money millions in the 1929 stock market crash, he got back on his feet, as good fighters do, and lived on until the age of 87, a beloved icon of a cherished era.

Leave A Comment