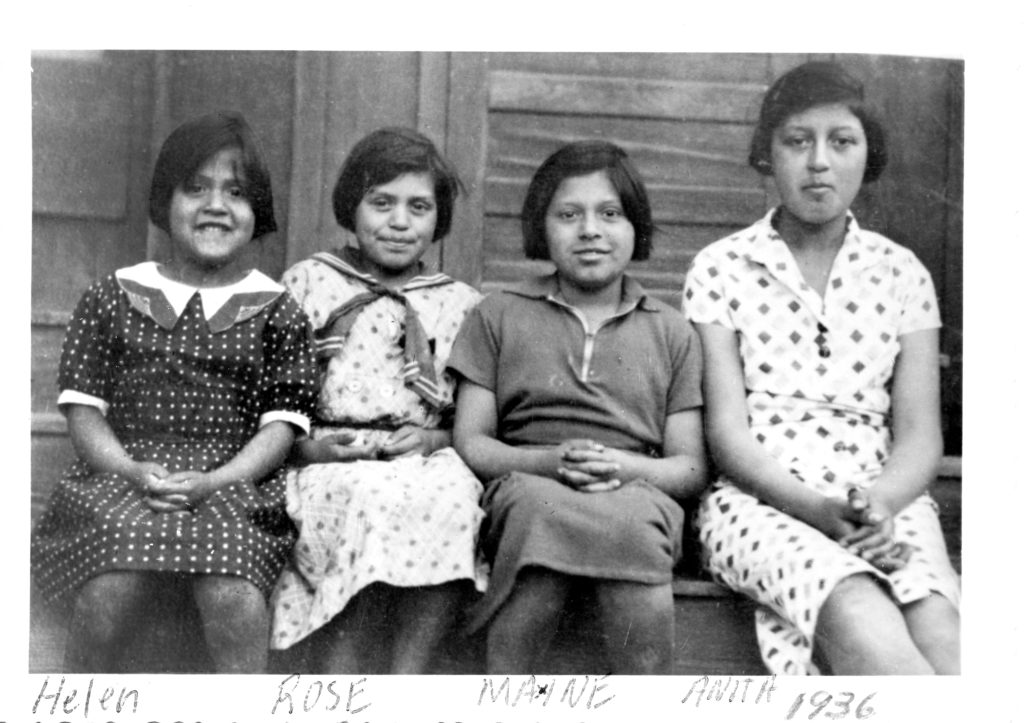

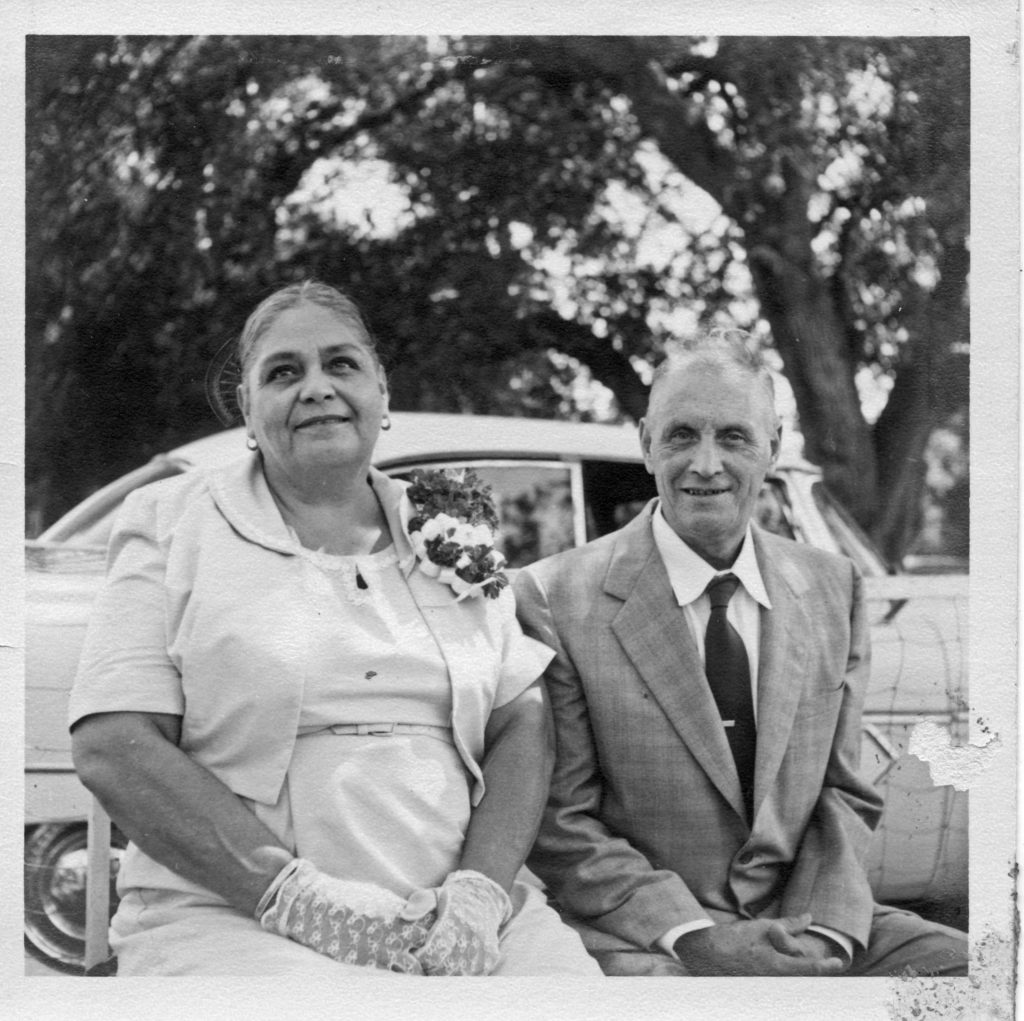

The Chavez sisters in 1936

FEATURES | By Mark Lewis

Hidden History

The Chavez sisters in 1936

For almost a century, Ojai’s remarkable Chavez family has played an unsung role in the building of this community. Now, the Ojai Valley Museum plans to recognize their contributions.

Turning 90 is a big deal, so when Ojai native Helen Chavez Peterson celebrates that milestone on June 7, she plans to do it in style, with a big family gathering at the Banquet Room at the Soule Park Golf Course clubhouse.

The location is apt, given Helen’s longtime interest in Ojai history. Soule Park is named for the pioneer Ojai family that once owned the ranch acreage that now comprises the park and the golf course. The last of the Soules, sisters Nina and Zaidee, refused all offers from developers who wanted to subdivide their ranch and build houses. Instead, the sisters gave it to the county for everyone to enjoy.

Nowadays, only a few old-timers remember who the Soules were. But Helen and her sister Rose Chavez Boggs remember them well. Zaidee Soule was the town librarian during the 1930s and ‘40s, when the Chavez siblings were regulars at the library — which, then as now, was located at the corner of Ojai Avenue and Ventura Street.

“We all knew them,” Rose says. “Especially Helen, who went to the library all the time.”

Like the Soule sisters, the Chavez sisters are the custodians of a rich family legacy. Unlike the Soules, Rose and Helen have no ranch to donate for a park that would immortalize the Chavez name. But they will share their family stories with the community in May 2021 when the Ojai Valley Museum opens “Founding Familias II,” the follow-up to last year’s exhibit about Ojai during the Rancho Era.

“The idea with both these ‘Familias’ exhibits is to foreground the contributions of Mexican-American families,” says Wendy Barker, the museum’s executive director. “Too often, the roles they played are overlooked in the history books. You shouldn’t have to donate a park to be honored by posterity.”

THE CHAVEZ STORY begins with Rose and Helen’s parents, Daniel and Hortense Chavez. Dan’s family had deep roots in New Mexico as early Spanish settlers there, but after New Mexico became part of the U.S., Dan’s grandfather moved south of the border and settled in the state of Michoacán. Dan was born there in the mid-to-late 1890s (the exact year is uncertain). He was still a young boy in the early 1900s when his parents moved the family north of the border, settling first in East Los Angeles and then in Hueneme (now Port Hueneme).

Hueneme was surrounded by Oxnard, home of the sugar beet and the lima bean, and of the people who milled them. Dan trained to be a chemist in a sugar-beet factory, but his duties also included making deliveries to local farms and ranches.

“He would deliver stuff to the Friedrich ranch in Oxnard,” Helen says. “My mother was working for the Friedrich family as a kitchen helper.”

Hortense Lopez y Carrillo was born in Hueneme in 1900 to parents who descended from several prominent Californio families — folks who had trekked to California from Mexico in the late 1700s, and were among the founders of Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. Hortense and Dan married on July 21, 1919. Then Dan went to Mexico on a job, which kept him away from his new bride for several months.

“Sweetest girl wife,” he wrote her that December. “… My own, I had to stop for awhile and cry, you are so far away Darling. But only you and I know that I did cry. Told you once that I couldn’t love you more than I did at the time but absence certainly makes the heart grow fonder. Now I really know what love means and can see how much I love you.”

Their first two children, Dan Jr., and Anita, were born in Hueneme in 1920 and 1922, respectively. Then, opportunity beckoned from the Ojai Valley, where Dan’s brother Max was the caretaker at the upscale Foothills Hotel. Dan suffered from asthma, and Hortense also had lung issues, so both were attracted to the valley’s hot, dry climate. When Max wangled Dan a job at the hotel in 1923, the family pulled up stakes and moved to Ojai.

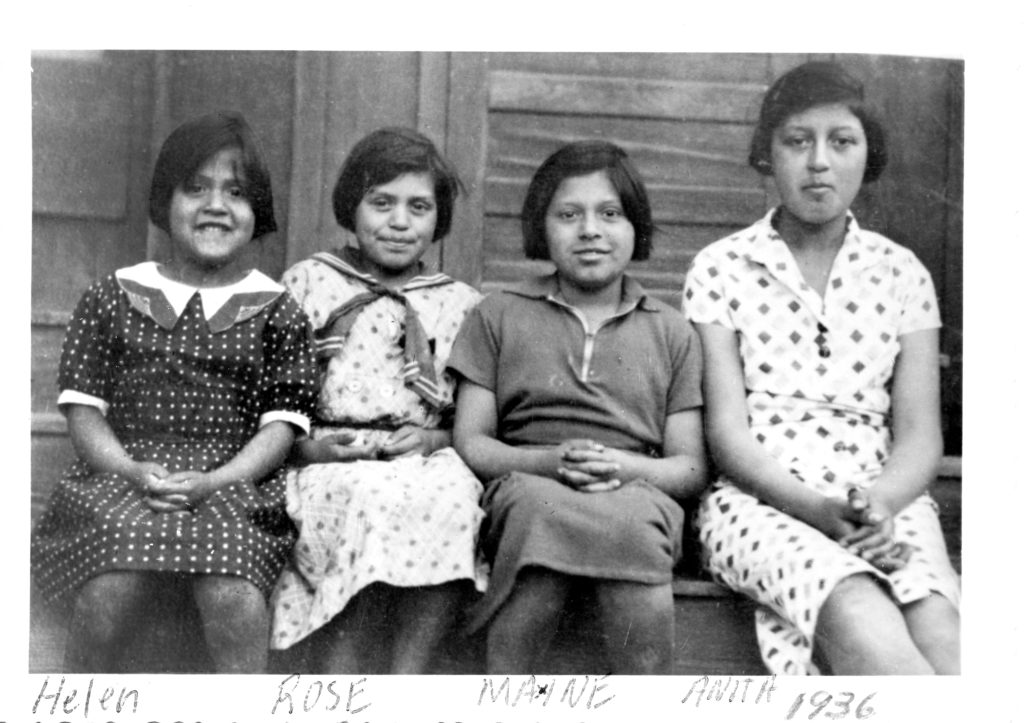

Dan & Hortense Chavez 40th anniversary 1959 copy

DAN SOON moved on from the hotel and became the caretaker of Civic Center Park, now known as Libbey Park. The wealthy philanthropist Edward Libbey was using Spanish Colonial Revival architecture to reinvent a previously unassuming frontier village as a picturesque Mission Era relic. Libbey’s right-hand man was Ojai real estate promoter J.J. Burke, and Burke’s right-hand man was Dan Chavez, at least when it came to managing the park.

The Chavezes rented a house on a Matilija Street lot that backed up to St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church. Their second son, Frank, was born in that house in 1924, followed by his sister Maxine in 1926. (That house is still there today, as is the former church building, which now houses the Ojai Valley Museum.)

When Dan decided to buy an empty lot on Lion Street and build a house for his growing family, he ran into a problem. In that era, restrictive deed covenants prevented most Ojai parcels from being sold to people of color. Dan got around that by telling the lot’s owner that he was of French descent, and pronouncing his name “Cha-vey,” a la Francaise. The ruse worked, and Dan bought the lot and built the house himself. It was there that he and Hortense welcomed a fifth child to their growing brood.

“I was born on Lion Street on Jan. 12, 1928,” Rose says. “It was a dirt road back then.”

Helen, the baby of the family, was born in the same house two years later. Dan and Hortensia now had six mouths to feed, which was not easy during the Depression years of the 1930s. The Ojai Civic Association paid Dan only $56 per month to maintain the park. To make ends meet, Dan moonlighted as a carpenter; pulled night shifts at Bill Baker’s famous bakery; and spent his weekends tending other people’s gardens and building rock walls. He also formed his own orchestra, which played private parties.

“He worked around the clock,” Rose says. “No vacations. I’m not sure he ever had a day off.”

Even so, money was tight. The kids all did their bit to bring in more.

“I milked the goats, took care of the chickens, ducks and rabbits when we had them,” Rose says. “Sometimes we would gather watercress at Camp Comfort and I would go sell it door to door for five cents a bunch. Sold honey, Dad was a beekeeper. Anything to make money.”

Nevertheless, Dan found time to perform in plays and play music at the Ojai Art Center, which he had helped build. He kept the house on Lion Street well stocked with books and musical instruments. And he was a card-carrying member of the Theosophical Society.

“He was really a Renaissance Man,” Helen says.

Hortense, too, was culturally inclined. She wrote poems that were printed in the local newspaper under her pen name, Jasmine. And in her later years, she took up painting.

During the ‘30s, the family did not own a car, so once per year, Dan rented a limousine from Hunt’s Auto Livery to take his children to Los Angeles to attend ballets, L.A. Philharmonic concerts, and opera performances. The Chavez kids became highly accomplished musicians and singers and bandleaders; they played tennis at highly competitive levels; they participated in plays and folk dancing at the Art Center. And they all did well in school, despite having to endure occasional racial taunts from white classmates.

“There were kids that called me ‘dirty Mexican,’ and it annoyed me because my mother was so clean you could eat off the floor,” Rose says. “She scrubbed them on her hands and knees!”

Anti-Hispanic prejudice did not deter the Chavezes from setting ambitious goals and achieving them. All six siblings graduated from Nordhoff High School and went on to Ventura College and then to four-year colleges. Frank became a World War II hero as a radio-gunner for the Army Air Corps in the Pacific Theater. (He later served in Korea as well.) Dan Jr. was elected president of Nordhoff’s senior class in 1939, and went on to earn a doctorate at Penn State.

But prejudice did at first keep Dan Jr. from getting hired as a professor at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo.

“He changed his last name to Chase, and then got the job,” Helen says. The three eldest siblings — Dan Jr., Anita and Frank — did not return to Ojai to live after their college days were over. But Maxine, Rose and Helen — and their parents — would continue to play important roles in the ongoing Ojai story.

THREE major institutions that helped put Ojai on the map — the Music Festival, the Ojai Valley Tennis Tournament and the Ojai Valley Inn — would not exist today, were it not for key decisions the community made in the aftermath of World War II. The Chavez family was involved in all three projects.

Rose discovered tennis as a child visiting the downtown park. Maintaining its courts was one of her father’s jobs as caretaker, especially during the last weekend of April when “The Ojai” tournament was held each year.

“I would sit there all day long, watching the tennis balls go back and forth,” she says.

Rose went on to become a very talented and successful player. She competed in The Ojai as a teenager, until the advent of World War II when the tournament shut down for the duration. The war ended in 1945, but The Ojai did not resume in 1946. For various reasons, the tournament was not sustainable without strong community support — and the community stepped up to save it. Rose was among the volunteers who refurbished the neglected courts and generally did what it took to ensure the tournament’s survival. Play resumed in April 1947, and The Ojai has not missed a year since.

At the time, Rose and Maxine comprised the No. 1 doubles team at Ventura College, and when Rose went on to UC Berkeley, she was the No. 1 singles player there. In later years she continued to compete in The Ojai and elsewhere, often paired with her longtime doubles partner Norma King. (At The Ojai one year, Rose and Norma lost a match 6-3, 6-2, to a doubles team that included the future legend Billie Jean King.)

“I played tennis for 70 years,” says Rose, who has been a fixture at The Ojai since 1932 as a spectator, player, coach and volunteer.

Rose, Maxine and their father also were involved in another key project that made its debut around the same time that The Ojai sprang back to life. During the war, the defunct Ojai Valley Country Club had been taken over by the Army as a training camp. When the Army moved out, the Navy moved in. When the war ended and the Navy pulled out, the property seemed likely to be sold to a developer and subdivided for houses. But local golf enthusiasts saved the course by lining up investors to erect a hotel on the site.

The manager and lead investor was Don B. Burger of Beverly Hills, who brought in movie-star investors such as Loretta Young and Irene Dunne, and thus ensured that the new hotel would be a popular destination for Hollywood celebrities. When the Inn opened in May 1947, Dan Chavez was the maintenance man, and Rose and Maxine were among the waitresses in its restaurant, serving meals to the likes of Jack Benny and Charlie Chaplin.

“And I worked there as a nanny for Don Burger’s son,” Helen says.

Helen played a bigger role in the third big project that made its debut during that epochal spring of 1947 – the Ojai Music Festival. As a budding opera singer, Helen naturally gravitated to a project that involved classical music.

“They asked for volunteers at Nordhoff, and I was the only one who went,” she says. “I worked in the festival office as a gofer.”

When the festival welcomed its first concertgoers on May 4 at Nordhoff Auditorium (now Matilija Auditorium), it was 16-year-old Helen Chavez who greeted them.

“I was the head usher,” she says. “I was standing in front of the doors, in a formal gown.”

The next day, the Ventura County Star-Free Press ran a photo of Helen in her gown, to illustrate a story about the Music Festival’s inaugural concert.

The festival was an indoor event in its early years, until the day its co-founder John Bauer asked Helen for suggestions about how to sell more tickets to local residents.

“He said, ‘Helen, you’ve lived here all your life. What would you like to see us do?’ I said, ‘Well, I’ve always wanted to go to a concert in the park.’ He took it and ran with it.”

For the 1952 festival, Bauer moved some of the concerts to an outdoor setting in Civic Center Park. The experiment was a success, and Bauer’s successors built the open-air bowl that remains the festival’s main venue today.

Helen was very serious about her singing career. She went to Europe to take voice lessons and remained there for six years, supporting herself by working as a teacher in England, Spain, Turkey, Germany and France.

“I studied voice at La Scala one summer,” she says. But at the time, young opera singers needed wealthy patrons to support their careers, and Helen did not have one. By the mid ‘60s she was back in Ojai, teaching at San Antonio School. Later she moved to Mira Monte Elementary.

“I taught a total of 50 years,” she says.

She also continued to sing, sharing her beautiful contralto voice with her fellow parishioners at St. Thomas Aquinas Church.

“I sang at all the weddings and funerals, and Maxine played the organ,” she says.

Maxine had returned to raise her four children after the early death of her husband, Joseph Tempske. Rose and her husband, Ben Boggs, were already here, raising their four children. Rose taught at Ojai Elementary, Summit, Topa Topa Elementary and Meiners Oaks Elementary schools. Maxine worked in administration at Nordhoff before later becoming a caregiver. Meanwhile, Helen married Roy Peterson and had a son of her own.

In the mid 1960s, all three sisters were involved in the founding of the Ojai Valley Mexican Fiesta, which sponsors an annual community party (usually in Libbey Park) to raise money for scholarships for local students of Latin American heritage.

Rose and Helen were longtime volunteers at the Ojai Valley Museum, as was Helen’s son, Vincent. Rose also served for three decades on the City of Ojai Historical Preservation Commission.

By doing community service, the sisters were following in their father’s footsteps. For example, after he was no longer employed by the Civic Association to maintain the downtown park, he continued to spruce it up as a volunteer before The Ojai tournament, the Music Festival and other events that took place there.

“He worked like a dog,” Rose says. “I don’t remember him ever getting a thank-you.”

Dan Chavez Sr. died in 1981, and Hortense in 1983. Eight of their direct descendants still reside in the Ojai Valley — Rose and her sons Michael and Dan Boggs; Helen and Vincent; and Maxine’s granddaughter Jazmin Tempske Charlesworth, and her young sons Cayden and Shepard. (Maxine died in 2017, at the age of 90.) Many cousins from out of town will join them at the Soule Park Banquet Hall on June 7 to celebrate Helen’s 90th birthday. It should be quite a party.

The clan will convene again at the museum in May 2021 for the opening reception of “Founding Familias II,” the exhibit that will highlight the history of their family, and other local families of Hispanic descent.

None of Dan and Hortense’s surviving descendants has Chavez as a last name. But all are proud of their heritage. When the Ojai City Council last year honored Rose with a Lifetime Achievement in Historical Preservation Award, she was disappointed to note that the plaque omitted her maiden name, which she often uses as her middle name. It just called her Rose Boggs.

“If they had contacted me,” she says, “I would have insisted that they put ‘Chavez’ in my name.”

Research contributed by Laurie Browne.

Leave A Comment