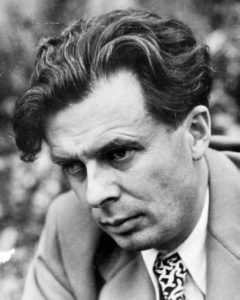

John Broesamle, drawing by Sandy TreadwellFEATURE | By Mark Frost

A Man of Uncommon Vision

The third time John Broesamle lost his sight he thought it was gone for good. Starting at the age of 45, glaucoma had gnawed away at his optic nerves for 20 years, twice before leaving him partially blind, the second time taking his right eye for good. Only the timely, and by any measure extraordinary, intervention of surgeons at the UCLA Stein Eye Institute had left him with a still functional left eye.

This time, in 2008, the director of the Institute sat him down to say that they’d done everything they could for him. After 20 surgeries, a run of experimental therapies, and countless other cutting-edge procedures, they’d run out of options.

He’d been half-expecting the bad news. The quality of this darkness was different; in the past he’d been able to detect murky shapes, streaks of light, and on bright days could still hike near his East End home by following the white lines on the edge of the road. Only blackness, this time, deep and impenetrable.

Within days he became a client of the Braille Institute, ready to learn a new alphabet. He’d fought a good fight, made his peace with the possibility that, one day, this would be his fate and never complained. That day was here. No reason to complain – he never complained. This was his new reality, for the duration; now he had to learn how to be blind.

But the timing was so damned inconvenient. There was still the small matter of protecting the Ojai Valley to sort out. How was he going to pull that off if he couldn’t even see it?

The best historians embrace the idea that their chosen task of making sense of the past is most essential to the degree that it helps us understand and prepare for the future. At the highest levels it’s not just a profession, it’s a calling. John heard the call for the first time in 1961, as an undergrad at the University of California, Berkley.

His dorm group had been summoned to attend a dinner in honor of the revered British writer Aldous Huxley. The author of “Brave New World” had requested the dinner because he wanted to meet “an average group of American college students.” At 67, the brilliant and famously eccentric Huxley had decided that young Americans represented a perfect control group for grasping what sort of future lay in store for Western civilization. When they sat down to dinner, by chance John ended up sitting two chairs away from him.

Dressed in a bilious yellow/grey suit — with pant legs a good four inches too short — and soft spoken to the point of inaudible, Huxley seemed a good deal more interested in what was on his plate than he was in studying John and his classmates. Then John realized he was hovering inches over his dinner because he almost completely blind, and later learned that Huxley had suffered from serious eye issues since adolescence.

Then the classmate next to John asked: Do you think your predictions in “Brave New World” will come true? Huxley mumbled, never looking up from his food: “Don’t you know my answer to that? I published it three years ago.”

John was one of the few at the table who could hear him. He was also the only student there who had actually read “Brave New World Revisited,” in which Huxley stated in no uncertain terms that his dystopian vision of an advanced Western society consumed and corrupted by its obsession with pleasure was a ship that had already sailed.

The evening went downhill from there. Grumpy and out of sorts, Huxley was openly disappointed in the quality of the questions the students asked. It seemed whatever conclusions he’d apparently already published about the hopelessness of the “average American youth” the dinner had only reinforced. Confirmation bias set in over the salad course.

But John came away thinking: Maybe a real historian would be more interested in examining the facts and drawing a more rigorously objective conclusion. This navigational nudge toward the course he was plotting for his own career proved decisive.

That evening was also where, unbeknownst to John as yet, his connections to the Ojai Valley began. Huxley, some 20 years Within days he became a client of the Braille Institute, ready to learn a new alphabet. He’d fought a good fight, made his peace with the possibility that, one day, this would be his fate and never complained. That day was here. No reason to complain — he never complained. This was his new reality, for the duration; now he had to learn how to be blind.

But the timing was so damned inconvenient. There was still the small matter of protecting the Ojai Valley to sort out. How was he going to pull that off if he couldn’t even see it?

The best historians embrace the idea that their chosen task of making sense of the past is most essential to the degree that it helps us understand and prepare for the future. At the highest levels it’s not just a profession, it’s a calling. John heard the call for the first time in 1961, as an undergrad at the University of California, Berkeley.

An encounter with eccentric writer and philosopher Aldous

Huxley, “Brave New World,”

nudged John Broesamle

toward the pursuit of history as a career.

His dorm group had been summoned to attend a dinner in honor of the revered British writer Aldous Huxley. The author of “Brave New World” had requested the dinner because he wanted to meet “an average group of American college students.” At 67, the brilliant and famously eccentric Huxley had decided that young Americans represented a perfect control group for grasping what sort of future lay in store for Western civilization. When they sat down to dinner, by chance John ended up sitting two chairs away from him.

Dressed in a bilious yellow/grey suit — with pant legs a good four inches too short — and soft spoken to the point of inaudible, Huxley seemed a good deal more interested in what was on his plate than he was in studying John and his classmates. Then John realized he was hovering inches over his dinner because he almost completely blind, and later learned that Huxley had suffered from serious eye issues since adolescence.

Then the classmate next to John asked: Do you think your predictions in “Brave New World” will come true?

Huxley mumbled, never looking up from his food: “Don’t you know my answer to that? I published it three years ago.”

John was one of the few at the table who could hear him. He was also the only student there who had actually read “Brave New World Revisited,” in which Huxley stated in no uncertain terms that his dystopian vision of an advanced Western society consumed and corrupted by its obsession with pleasure was a ship that had already sailed.

The evening went downhill from there. Grumpy and out of sorts, Huxley was openly disappointed in the quality of the questions the students asked. It seemed whatever conclusions he’d apparently already published about the hopelessness of the “average American youth” the dinner had only reinforced. Confirmation bias set in over the salad course.

But John came away thinking: Maybe a real historian would be more interested in examining the facts and drawing a more rigorously objective conclusion. This navigational nudge toward the course he was plotting for his own career proved decisive.

That evening was also where, unbeknownst to John as yet, his connections to the Ojai Valley began. Huxley, some 20 years before, had become an integral part of the group of intellectuals and spiritual seekers centered around the sage of the East End, Jiddu Krishnamurti. Huxley’s close friendship and philosophical affinity with Krishnamurti would eventually lead to their collaborative founding of the Happy Valley School, now known as Besant Hill School. But John’s path to Ojai was only just beginning.

His parents were the ones who finished paving the way. John’s mother Josephine had family connections to the Ojai Valley and had visited often as a child all the way back in the 1920s. After 40 years teaching in the Long Beach Public school system, where John grew up, his father Otto retired with Josephine to a modest house in Ojai in 1972. Not long after his dinner with Huxley in 1961, John’s path took another turn. He was working for the season at a service station in Yosemite National Park, where his parents camped each summer. While enjoying a day off in the park’s Tuolumne Meadows he met another collegiate summer employee, Kathy Warne, an English major from University of the Pacific. A fateful meeting, of hearts and minds, they married three years later. The following year, after both graduated, the young couple headed for New York City, where John began working on his Ph.D in history at Columbia.

Four years later, the road turned again. Although they’d originally planned on staying in the East to launch their teaching careers, their mutual love of the High Sierras called them West. Now with two young children to support, when John received an offer from Cal State Northridge to join the faculty as a history professor they jumped at it. That same year, 1968, they made their first visit to Ojai and stumbled onto Bart’s Books, the local landmark that’s grown like Topsy since 1964, in and around a dentist’s old house. To two young dedicated bibliophiles — living on a budget — Bart’s became a treasure.

John and Kathy Broesamle

A few years later they were wandering through the downtown arcade, where the Music Festival was in progress in nearby Libbey Park and they heard a voice on a P.A. system announce “Mr. Copland will conduct in 10 minutes.” Aaron Copland? They bought tickets, watched Copland conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic from the lawn and felt the gravitational pull of Ojai draw them closer. That led to frequent camping trips in Dennison Park, on the lip of the Shangri-La view of the Valley. Ojai began to steadily occupy a more central place in their imaginations.

Something larger was at work as well. As environmental issues, and the health of the planet, began to work their way into the national consciousness, John realized a personal trauma had placed them at their forefront of his own awareness since the age of eight. He’d enjoyed a bucolic Our Gang childhood in the lush green agricultural fields and forests of suburban Long Beach. After a long summer idyll in Yosemite, he returned to find his beloved fields and forests had been replaced by the planned, prefab community of Lakewood, one of the first “planned city” projects in California. In one stroke, as if its entire grid had fallen from the sky, all the green was replaced by asphalt as far as his eyes could see. At one point, a new house went up every seven and a half minutes.

John and Kathy’s devotion to nature soon evolved into the birth of their work as conservationists, which began in earnest during the 1970s after they moved to Thousand Oaks. Kathy had begun building and running an award-winning speech therapy program for the Conejo Valley School System, and John was soon to become a full professor at Northridge.

At the outer ring of the sprawling L.A. suburbs, Thousand Oaks had experienced a decade of explosive growth that threatened to consume its vibrant open spaces. At the frenetic height of their teaching career, without a dime or an hour to spare, in 1979 John and Kathy volunteered to take what turned out to be leading roles in “Measure A,” the granddaddy of California grassroots ballot initiatives. Perceived as a radical idea at the time, it proposed applying “metered local growth” to the explosive metastasis of the L.A. metroplex. It was ferociously opposed by a phalanx of powerful outside economic forces that wrote huge checks to squash it. Struggling to make ends meet, knocking on doors, manning phones and handing out flyers — STOP THE BULLDOZERS! — John and Kathy’s already brutal 80-hour weeks became 120-hour weeks, but they’d put their fingers on a pulse in the SoCal body politic few had realized existed. Spending a tiny fraction of their opponents, their baptism in local politics ended in a shockingly decisive David v. Goliath victory at the polls. “Measure A” led to a more sane and measured development pattern for Thousand Oaks, and to this day is considered a model of civic conservation. For John and Kathy, this successful symbiosis of local politics and environmental issues set the template for what was to come.

When John’s parents passed in the early ‘80s, John and Kathy bought their own piece of the Ojai Valley, a humble ranch house off Thacher Road in 1987. It started as a second home, the way so many outsiders arrive here, to their main house in Thousand Oaks, but Kathy soon took a job with the Ojai school district, and, within three years, they’d landed here full time. The move was prompted in no small part by John’s first scare with glaucoma, which cost him half his right eye’s vision, and a series of ominous changes in his left between check-ups foreshadowed trouble, but the good doctors at the Stein Eye Institute succeeded in stabilizing him.

The more relaxed pace of Ojai life would help, they told themselves. Less stress, more solitude, gardening and reading, and hikes in the hills and woods. John had books to write, and they had grandkids to look forward to, so they swore off community activism as well, no more tilting at political windmills, they’d done their part, let someone else fight the good fight for a while.

But Ojai has a way of drawing useful decisive.

That evening was also where, unbeknownst to John as yet, his connections to the Ojai Valley began. Huxley, some 20 years before, had become an integral part of the group of intellectuals and spiritual seekers centered around the sage of the East End, Jiddu Krishnamurti. Huxley’s close friendship and philosophical affinity with Krishnamurti would eventually lead to their collaborative founding of the Happy Valley School, now known as Besant Hill School. But John’s path to Ojai was only just beginning.

His parents were the ones who finished paving the way. John’s mother Josephine had family connections to the Ojai Valley and had visited often as a child all the way back in the 1920s. After 40 years teaching in the Long Beach Public school system, where John grew up, his father Otto retired with Josephine to a modest house in Ojai in 1972. Not long after his dinner with Huxley in 1961, John’s path took another turn. He was working for the season at a service station in Yosemite National Park, where his parents camped each summer. While enjoying a day off in the park’s Tuolumne Meadows he met another collegiate summer employee, Kathy Warne, an English major from University of the Pacific. A fateful meeting, of hearts and minds, they married three years later. The following year, after both graduated, the young couple headed for New York City, where John began working on his Ph.D in history at Columbia.

Four years later, the road turned again. Although they’d originally planned on staying in the East to launch their teaching careers, their mutual love of the High Sierras called them West. Now with two young children to support, when John received an offer from Cal State Northridge to join the faculty as a history professor they jumped at it. That same year, 1968, they made their first visit to Ojai and stumbled onto Bart’s Books, the local landmark that’s grown like Topsy since 1964, in and around a dentist’s old house. To two young dedicated bibliophiles — living on a budget — Bart’s became a treasure.

A few years later they were wandering through the downtown arcade, where the Music Festival was in progress in nearby Libbey Park and they heard a voice on a P.A. system announce “Mr. Copland will conduct in 10 minutes.” Aaron Copland? They bought tickets, watched Copland conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic from the lawn and felt the gravitational pull of Ojai draw them closer. That led to frequent camping trips in Dennison Park, on the lip of the Shangri-La view of the Valley. Ojai began to steadily occupy a more central place in their imaginations.

Something larger was at work as well. As environmental issues, and the health of the planet, began to work their way into the national consciousness, John realized a personal trauma had placed them at their forefront of his own awareness since the age of eight. He’d enjoyed a bucolic Our Gang childhood in the lush green agricultural fields and forests of suburban Long Beach. After a long summer idyll in Yosemite, he returned to find his beloved fields and forests had been replaced by the planned, prefab community of Lakewood, one of the first “planned city” projects in California. In one stroke, as if its entire grid had fallen from the sky, all the green was replaced by asphalt as far as his eyes could see. At one point, a new house went up every seven and a half minutes.

John and Kathy’s devotion to nature soon evolved into the birth of their work as conservationists, which began in earnest during the 1970s after they moved to Thousand Oaks. Kathy had begun building and running an award-winning speech therapy program for the Conejo Valley School System, and John was soon to become a full professor at Northridge.

At the outer ring of the sprawling L.A. suburbs, Thousand Oaks had experienced a decade of explosive growth that threatened to consume its vibrant open spaces. At the frenetic height of their teaching career, without a dime or an hour to spare, in 1979 John and Kathy volunteered to take what turned out to be leading roles in “Measure A,” the granddaddy of California grassroots ballot initiatives. Perceived as a radical idea at the time, it proposed applying “metered local growth” to the explosive metastasis of the L.A. metroplex. It was ferociously opposed by a phalanx of powerful outside economic forces that wrote huge checks to squash it. Struggling to make ends meet, knocking on doors, manning phones and handing out flyers — STOP THE BULLDOZERS! — John and Kathy’s already brutal 80-hour weeks became 120-hour weeks, but they’d put their fingers on a pulse in the SoCal body politic few had realized existed. Spending a tiny fraction of their opponents, their baptism in local politics ended in a shockingly decisive David v. Goliath victory at the polls. “Measure A” led to a more sane and measured development pattern for Thousand Oaks, and to this day is considered a model of civic conservation. For John and Kathy, this successful symbiosis of local politics and environmental issues set the template for what was to come.

When John’s parents passed in the early ‘80s, John and Kathy bought their own piece of the Ojai Valley, a humble ranch house off Thacher Road in 1987. It started as a second home, the way so many outsiders arrive here, to their main house in Thousand Oaks, but Kathy soon took a job with the Ojai school district, and, within three years, they’d landed here full time. The move was prompted in no small part by John’s first scare with glaucoma, which cost him half his right eye’s vision, and a series of ominous changes in his left between check-ups foreshadowed trouble, but the good doctors at the Stein Eye Institute succeeded in stabilizing him.

The more relaxed pace of Ojai life would help, they told themselves. Less stress, more solitude, gardening and reading, and hikes in the hills and woods. John had books to write, and they had grandkids to look forward to, so they swore off community activism as well, no more tilting at political windmills, they’d done their part, let someone else fight the good fight for a while.

But Ojai has a way of drawing useful

John Broesamle, drawing by Sandy Treadwell

John Broesamle, drawing by Sandy Treadwell

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Leave A Comment