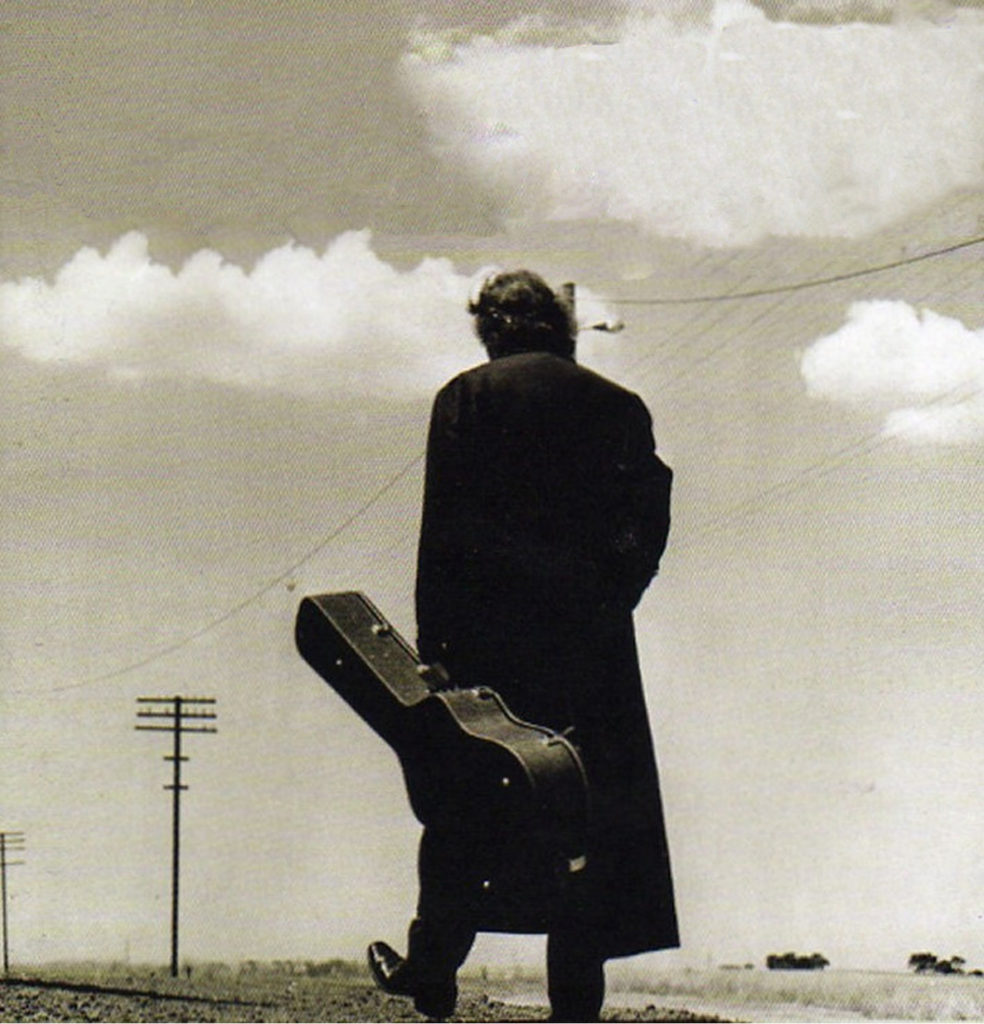

Johnny Cash: The Story of His Ojai Valley Blues

In 1961, the country star built his dream house in Casitas Springs. Then he spiraled out of control.

Johnny Cash used to sweep into Casitas Springs like he owned the place. But those days were over. On the morning of Jan. 10, 1968, Cash passed quietly through town while en route to LAX from his parents’ home in Oak View. He no longer owned the big house on the hill above Nye Road in Casitas; it had gone to Vivian Cash in the divorce, which had become final a week earlier. Vivian was in Las Vegas that day, getting ready to marry Dick Distin on Jan. 11.

And Johnny? He was on his way to prison.

From Los Angeles, he would fly to Sacramento to begin rehearsals for his Jan. 13 concert in Folsom State Prison. The concert would be recorded for a live album, “Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison,” which would become an enormous hit, transforming Cash from a fading country music star into a crossover pop-culture phenomenon. He would even end up with his own network television show. But he could not foresee this looming transformation as he drove south through Casitas Springs that day. What he knew was that it was the end of an era: his troubled sojourn in Southern California, which he mostly had passed in the Ojai Valley.

These had been the worst years of his life. He had fallen into an amphetamine addiction that damaged his career, ruined his marriage and damn near killed him. After leaving Vivian and moving to Nashville, he eventually had fought his way clear from the pills, with help from June Carter and her family. But as he passed through Casitas that day, he must have at least glanced up at the house he had built for Vivian almost seven years earlier, and perhaps shaken his head at the attendant ironies.

This was his dream house. He had supervised the design himself, obsessing over every detail. Eventually the house had become like a prison to him, and now he was free. Yet here he was, on his way to Folsom to sing his old hit “Folsom Prison Blues” – a song inspired in part by his desperate desire to marry Vivian and live with her forever.

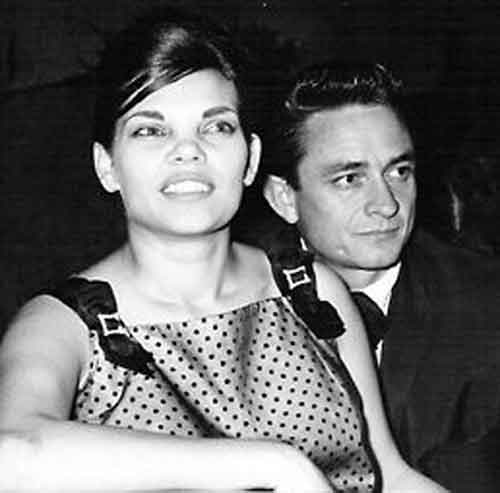

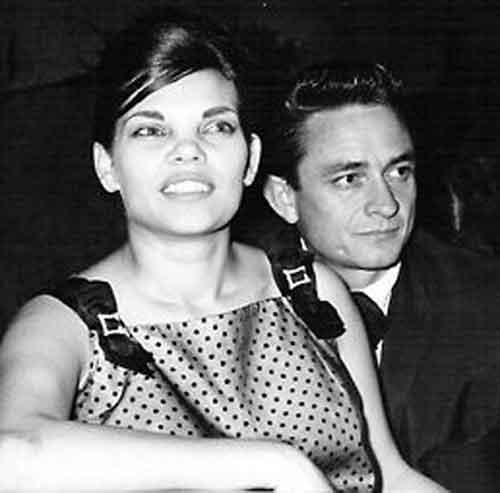

FOR Johnny Cash and Vivian Liberto, it was pretty much a case of love at first sight. They met at a roller-skating rink in San Antonio in the summer of 1951. Johnny was 21, a sharecropper’s son from Arkansas who recently had joined the Air Force and was undergoing radio-intercept training at Brooks Air Force Base. Vivian, 17, was a Catholic schoolgirl heading into her senior year. Something sparked between them that would endure throughout the three years of Johnny’s overseas service, during which he deluged her with love letters urging her to marry him.

Vivian Liberto and Johnny Cash shortly after their wedding.

One day, while stationed at Landsberg Air Force Base near Munich, Cash viewed a Hollywood melodrama called “Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison.” The film inspired him to write a song about a Folsom inmate who had “shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die.” The inmate is tormented by the sound of a passing train, which he imagines is carrying passengers to faraway places. “I’m stuck in Folsom Prison,” he laments, “where time keeps draggin’ on. And that train keeps rolling, on down to San Antone.”

That train was following a peculiar route, since Folsom is in California while San Antonio is in Texas. But read between the lines: Cash was stuck in Germany, while his commanding officer regularly boarded a flight back home to San Antonio to consult with his superiors at Brooks Air Force Base. “I want to stow away on his plane, but I couldn’t manage it,” Cash wrote to Vivian. “Maybe I can get promoted to colonel pretty soon, and I can go to San Antone every month like he does.” In the song, the plane becomes a train, but the destination remains the same:

San Antonio, where Vivian was waiting to marry him. That was what freedom meant to Johnny Cash in 1953.

He finally made it back to San Antonio when his hitch was up. He married Vivian in 1954 and they settled in Memphis, where Johnny worked as a door-to-door appliance salesman. Then, in 1955, he and his band walked into the Sun Records studio to audition for Sam Phillips, the man who had discovered Elvis Presley. By July of that year, Johnny’s first single, “Cry, Cry, Cry,” was climbing the country charts. On July 30 he returned to the Sun studio to cut a follow-up single: “Folsom Prison Blues,” which hit the Top 10. Cash was just getting started. His next release, “I Walk the Line,” rose to No. 1 and crossed over to the pop charts. Johnny Cash was now a big star, and — like Elvis before him — he had outgrown Sun Records. In 1958 he signed with a major label, Columbia Records, and moved his growing family to Los Angeles.

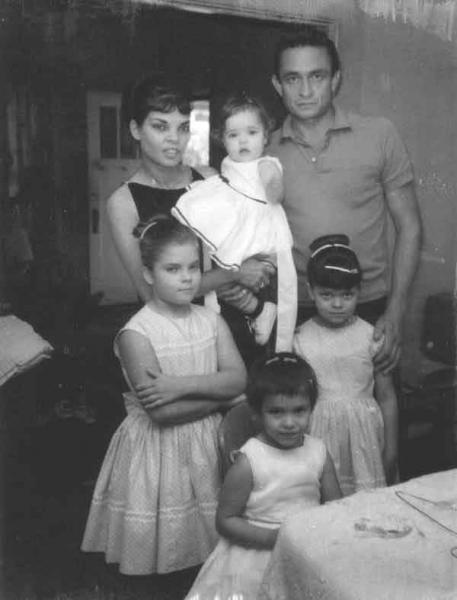

“BY the time we left Memphis for California … we had three daughters and a marriage in bad trouble,” Cash wrote in his 2003 autobiography. He was becoming addicted to pep pills, and to the excitement of life on the road. Vivian was home taking care of 3-year-old Rosanne, 2-year-old Kathy and baby Cindy; she could not join Johnny on the road, nor did she care to. She wanted him to come home to her, like a normal husband.

To house his family in comfort, Cash bought Johnny Carson’s old house on Hayvenhurst Avenue in Encino. Cash hoped to lure his parents west too, but Ray and Carrie Cash were not city folk, nor even suburban folk; they would not cotton to life in the San Fernando Valley. Then one day, while Johnny was out for a drive with his manager, he stumbled across the Ojai Valley. Here, he thought, was the perfect spot for his parents: an isolated, semi-rural paradise that still lay within easy driving distance of L.A. He bought a trailer park north of Oak View, renamed it the Johnny Cash Trailer Rancho, and asked Ray and Carrie to come out and run it for him. They agreed.

The trailer park was located on the west side of Ventura Avenue, just north of what is now Willey Street. (It’s still there; nowadays it’s called the Country Village Mobile Home Park.) Ray and Carrie lived there in a comfortable wood-frame house, where they frequently played host to Johnny and Vivian and the girls, visiting from Encino. Before long, Johnny had decided to move his own family to the Ojai Valley, too.

Part of Ojai’s appeal was its pristine air quality compared to L.A. “Rosanne was allergic to the smog, coming home from school every day with tears running off her chin,” Johnny wrote. But clean air was not his only motivation. Cash was a country boy at heart; when not on the road with his band, he preferred to live where he could hunt and fish. The Ojai Valley was his kind of place — especially the west side communities that were home to so many former Dust Bowl migrants from Oklahoma and Texas. These folks worked in the oilfields, and on Saturday nights they crowded into Okie’s lounge in Foster Park to listen to country music and raise a little hell. (Cash had played this lively venue himself at least once, back in 1956 when it was still known as Moose Hall.)

Johnny also had friends in the area, like the “Rawhide” actor Sheb Wooley. There were also Cash’s Columbia Records label mates Johnny and Jonie Mosby, “Mr. and Mrs. Country Music,” who lived in Ventura and owned the popular Ban-Dar club on East Main Street.

“We did tour with him a lot,” Jonie told the Ojai Quarterly. (These days she is known as Jonie Mitchell, and lives in Santa Paula.)

Cash decided to move his business office to Ventura and build his dream house in the nearby mountains. Somehow he ended up on a hill in Casitas Springs. Not everyone thought this was a good idea.

“I remember when Cash had his house built on the side of a mountain in Casitas Springs,” the country singer David Frizzell told the OQ. “My cousins lived at the foot of Johnny’s mountain in a trailer park, and I’d look up to Johnny’s place every time we’d go to visit.”

Frizzell, a former Ojai resident, said he used to wonder why Cash choose to live in Casitas Springs instead of Ojai. “I never asked him why, although I did wonder why, because Casitas Springs was not the nicest place to live.”

Perhaps that was exactly what attracted Cash to the place: It was an unpretentious little town of modest homes and working-class people. His kind of people.

“I think it reminded him of home, of Arkansas when he was grown up,” his daughter Kathy Cash told the OQ.

Be that as it may, Cash did not want to live in Casitas Springs, he wanted to live high above it. He bought himself 12 acres on that hill and built a steep, winding driveway up to the building site.

“I remember Dad taking us there after the road had been cut,” Kathy said. “And we’re on top of this hill going, ‘What? Why?’ I mean, there was nothing there.”

Johnny’s friend Walter “Curly” Lewis, a local contractor, filled in the blanks. Lewis built a five-bedroom house to Cash’s exacting specifications.

“At the building site, he lay down in the dirt and told Curly, ‘I want the master bathtub this big, and right here,’ ” Vivian wrote in her memoir, “I Walked the Line.”

“The house in Casitas was fabulous when it was finished,” she added. “It was a sprawling, 5,000-square-foot, ranch-style home with maid’s quarters and a huge, 15-by 30-foot kitchen that I loved.”

The house also featured an enormous built-in aquarium filled with exotic-looking fish. And the master bedroom featured a white carpet and a black ceiling, with silver flecks glittering here and there in the firmament.

“Dad wanted it to look like they were lying out under the stars at night,” Kathy said.

From her new living room window, Vivian gazed down upon her neighbors. The town’s population in 1961 was about 300. Before the Cashes moved in, its main claim to fame was that it was home of Howard Lee of Lee’s Frog Hatchery, which Life Magazine had once described as “one of the biggest bullfrog farms in the world.” Now Johnny Cash would be the biggest frog in this very small pond.

“I’m sure some people wondered why in the world we wanted to move from our comfortable neighborhood on Hayvenhurst to no-man’s-land,” Vivian wrote in her memoir. “But that’s what Johnny wanted, and Johnny always got whatever Johnny wanted. Besides, I was hopeful that getting him away from the city and into the country would settle him down. No more late-night partying. No more drinking. No more pills. No more whispered rumors of other women. I thought the change would do us good. I was more than ready for my little slice of heaven at the end of Tobacco Road.”

The Cashes moved in in the fall of 1961, shortly after the birth of their fourth daughter, Tara. Actually, it was Vivian and the girls who moved in; Johnny was on the road as usual. At a show in Dallas that December, he welcomed a new member to the cast of his touring “Johnny Cash Show.” This was June Carter, of the famous Carter Family. June was country-music royalty, born and bred, and — unlike Vivian — she was fully committed to the life of a touring performer.

“It wasn’t long after we moved that everything, I mean everything, started to fall apart,” Vivian wrote. “There were a lot of happy times before Casitas, but after the move the happy times came fewer and farther between. Johnny was on the road 250 days of the year now, with June Carter and her family in tow. His use of pills continued to worsen. And I was alone with four small children in a new house in the middle of nowhere.”

Johnny, in his autobiography, recalled the Ojai Valley very fondly, but conceded that his life there did not work out as he had hoped.

“I loved it there,” he wrote. “It was beautiful land. ‘Ojai’ means ‘to nest.’ Nesting wasn’t what I did, though.”

IN those days the Southern Pacific Railroad still ran orange trains from Ventura to the packinghouse on Bryant Street in Ojai. (The sight of that train passing through Casitas may have inspired Cash to cover the classic tune “Orange Blossom Special,” a Top 10 hit for him in 1965.) Lake Casitas was brand-new when the Cashes moved into the neighborhood – the dam had been completed in 1959, but the reservoir took years to fill up. Nevertheless, the lake had been stocked with largemouth bass and rainbow trout, and Johnny passed many pleasant hours there. In fact, he may have written his biggest hit there. “Ring of Fire” is credited to June Carter and Merle Kilgore — but Vivian Cash and Curly Lewis later claimed that Cash co-wrote it himself with Kilgore while floating on a boat in Lake Casitas, and gave his songwriter credit to June. His 1963 recording of the song spent seven weeks at No. 1, and crossed over to the pop charts too.

Johnny often took his daughters to the lake, or to Foster Park for picnics, or to Oak View to visit their grandparents. Vivian often drove them up to Ojai to go shopping in the Arcade. But the Cashes didn’t mix much in Casitas Springs.

“Some would say that it was the Royal Family living up on the hill,” said Doug Brown, who grew up in the town. “You could see the girls out playing in the yard.”

At Christmastime, Johnny would reach out to his neighbors by setting off fireworks, an old family tradition. He also used floodlights to illuminate a big aluminum cross he put up on the hill above his house, and he set up loudspeakers to blare Christmas carols that the whole town could hear. He was stunned one year when some people complained about the noise. “I didn’t think there was a Scrooge left,” he grumbled as he pulled the plug in the middle of “Joy to the World.”

On weekday mornings, Vivian would dress the girls in their school uniforms and drive them down the hill in her Cadillac to catch their bus to the Academy of St. Catherine in Ventura. The girls had few friends in Casitas Springs, but they did not lack for playmates. Johnny’s sister Reba and Vivian’s sister Sylvia had moved to the valley with their respective families, and they would bring their children over to visit.

“We had a lot of people visiting all the time,” Kathy said. “We had a great time living there. I loved it!”

Her sister Rosanne has a darker view. “It was horrible,” she told Cash biographer Steve Turner. “I don’t know what they were thinking. Dad was on the road all the time and they moved us up to the top of this mountain in this really poor township. We had the most money and the biggest house in the whole area, and we were perched up there all alone, and it was strange.”

Kathy fondly recalls the family’s menagerie of pets, which included dogs, ponies and a talkative parrot named Jethro. Rosanne, in her 2011 memoir “Composed,” focused on the scorpions, tarantulas and rattlesnakes that infested the yard. Kathy likes to talk about her father’s famous friends, such as Patsy Cline, who often gathered at the house for parties. Rosanne focuses on the drunken strangers who would periodically knock on the door late at night, hoping to meet their hero: “ ‘He’s not here,’ my mother would shout, slamming the door on them.”

Sometimes the drunken stranger at the door would be Johnny Cash himself. When strung out on amphetamines and tanked up on booze, he often seemed like a different, and less pleasant, person. His increasingly erratic behavior often brought him to the attention of local peace officers, like the ones who tried to pull Johnny’s Cadillac over late one night on the Ojai Freeway. He led them on a six-mile chase at speeds up to 90 mph before they finally caught him in Casitas, near his driveway. He had no driver’s license to show them, but he did have an explanation: “I just wanted to find out if I could still outrun a police car.”

Even when sober, Cash was often impetuous. One time he was out with some friends in the mountains near his home, taking target practice with his hunting rifles, when he scoped a deer on a faraway ridge. Deer were not in season and there were a couple of game wardens nearby, ready to confiscate his guns if he broke the rules. Cash was undeterred. He asked the wardens what the fine would be if he shot the deer.

“They kind of guessed and said, ‘Well, with what your guns are worth and the fines, no license, out of season and all, it would be about $3,000, probably,’ ” recalled W.S. “Fluke” Holland, who played drums in Cash’s band. (Holland tells this story in the book “I Still Miss Someone: Friends and Family Remember Johnny Cash.”)

Holland told Cash that he might as well go ahead and take the shot, because the deer was so far away that nobody could hit it anyway.

“Without saying a word, he stretched out on his stomach on the ground and propped up on his elbow and pulled the trigger,” Holland wrote. And Cash knocked down the deer. He and his friends surrendered the guns to the wardens, scrambled up the mountain to retrieve the deer, and took it down to Johnny’s parents’ place in Oak View. They dressed it, cooked it, started to eat it, and discovered that Cash had paid $3,000 for inedible venison.

“A damn alligator couldn’t have eaten it, that meat was so tough,” Holland recalled. “See, Johnny wanted to shoot that deer. He didn’t care what it cost, so he did. That was vintage Johnny Cash.”

Caroline Damas, who often babysat the Cash girls in those days, recalls Johnny as a very nice, down-to-earth man who was good to his children and good to his wife too – as far as Damas could tell. “Of course, people have problems, and you don’t always see them,” she added.

Cash, in his autobiography, makes those problems plain:

“It was a sad situation between Vivian and me, and it didn’t get better. I wasn’t going to give up the life that went with my music, and Vivian wasn’t going to accept that. So there we were, very unhappy. There was always a battle at home.”

Usually he would respond to a fight by walking out. He would grab a bunch of pills, jump in his camper, drive it deep into the backcountry, “and stay out there, high, for as long as I could. Sometimes it was days.”

One of these trips made headlines in June 1965, when sparks from the camper’s faulty exhaust pipe ignited a fire near Sespe Creek, deep in the Los Padres National Forest. Firefighters called in air tanker drops to extinguish the blaze, which raged for the better part of a week, scorched some 500 acres, and put at least 40 condors to rout from their sanctuary. When government lawyers later questioned him about the incident, Cash was once again high on pep pills, which fueled his arrogant answers:

“Did you start this fire?”

“No, my truck did, and it’s dead, so you can’t question it.”

“Do you feel bad about what you did?”

“Well, I feel pretty good right now!”

“But how about driving all those condors out of the refuge?”

“You mean those big yellow buzzards?”

“Yes, Mr. Cash, those yellow buzzards.”

“I don’t give a damn about your yellow buzzards. Why should I care?”

The government gave him a reason to care, by suing him for the cost of putting out the fire. He was fined $125,000, ultimately reduced to $82,000 in a settlement.

By now, Cash clearly was out of control. Later that summer he was banned from the Grand Ole Opry after he deliberately smashed the stage lights during a performance. And in October 1965 he made national news when he was arrested in El Paso for smuggling hundreds of pills across the border from Juarez.

On the increasingly rare occasions when he was home, he often was surly, even in public.

“My mom waited on him and his wife up at the Ojai Valley Inn many times,” Leslie Gibbeson Dey told the OQ. “She said he could be a real ass and that his wife would always apologize for him afterwards.”

In years past, Johnny’s hit songs had publicly expressed his love for Vivian: “Because you’re mine, I walk the line.” But in 1964, as the marriage crumbled, he went to No. 1 with “Understand Your Man,” which carried a very different message:

Don’t call my name out your window, I’m leavin’

I won’t even turn my head

Don’t sent your kinfolks to give me no talkin’

I’ll be gone, like I said

You’d just say the same old things that you’ve be sayin’ all along

Just lay there in your bed and keep your mouth shut

‘Til I’m gone

Don’t give me that old familiar cryin’ cussin’ moan

Understand your man

This would be Johnny’s last No. 1 song for several years, until “At Folsom Prison” put him back on top. His self-destructive antics were hurting his career. Jonie Mitchell recalls him stumbling into the Ban-Dar in Ventura, usually with Sheb Wooley in tow. “He’d drop in when he was about half-tanked,” she said. “He was going down, down, down.”

IN June 1966, Cash left to go on tour and never returned. In August, Vivian filed for divorce.

When the dust finally settled, she got the house in Casitas and Johnny’s share of the Purple Wagon Square mall in Oak View, an investment property he co-owned with Sheb Wooley. But Johnny retained the Johnny Cash Trailer Rancho, where his parents still lived. And so he returned to the Ojai Valley at least one more time, in January 1968, to visit Ray and Carrie. When he drove to LAX on Jan. 10, Ray came with him, to attend the Folsom concert. June was with him too; within three months, they would be married.

By this point in his life, Cash finally wasfighting back against his addiction, and was mostly staying sober. The show of course was a big success, and the resulting live album kicked his career into the stratosphere. He spent the rest of his life with June in Tennessee, where they both died in 2003. (For more on the Folsom concert and how it came about, see the companion story, “Jailhouse Rocked.”)

As for Vivian, she married Distin and moved to Ventura, where all four of her girls attended St. Bonaventure High School. Rosanne, who went on to become a country music star in her own right, recalls the move from Casitas as a positive turning point.

“It was as if, with that move, someone had opened all the windows and let the light and air inside,” Rosanne wrote in her memoir. “My mother almost immediately flourished, making a lot of friends, joining a garden club and a bowling league, taking dance lessons, playing card games, and hosting memorable parties.” Vivian died in 2005.

And the house? It’s still there, brooding over the (still) little town of Casitas Springs from behind the row of conical Cypress trees Johnny planted. Vivian sold the property to a family friend, Jack Newman, who lived there with his family for about 20 years before he sold it to the current owner, Montecito Fire Chief Chip Hickman.

But people still associate the place with Cash, especially since the 2005 release of the film “Walk the Line,” starring Joaquin Phoenix as Cash and Ojai’s own Reese Witherspoon as June Carter.

During the many years Newman lived there, he noticed a recurring phenomenon: Strangers periodically would pull off Ventura Avenue at Nye Road and point their cars up his long, winding driveway. They would drive all the way to the top, pause there for a moment or two, then turn around and leave without ever getting out of the car. They were trying to connect with an American legend.

“People would just drive up and drive back down again,” Newman said. “They just wanted to see where Johnny Cash lived.”

I 💘 The Man in Black!

Just ran into this and found it real interesting. Unaware of the connection to the Ojai Valley. Complex character for sure. Thanks for the story.

Great story. Really enjoyed it.