COMMUNITY | By Bret Bradigan

Nomad Gallery’s Final Week

Leslie Clark on camelback

Nomad Gallery will close at the end of June, ending its 23-year run with a month of sales, parties and bittersweet reminiscences. For one small retail space perched on the eastern edge of the Pacific Rim, it looms large in the lives of thousands of people in a country 8,000 miles away.

One example of how large: Before 2008, one in seven women in Niger’s most remote region would die during childbirth. Today, the number has fallen from six percent to zero. Hundreds of women are alive today because of the midwife training program developed by Nomad Gallery owner Leslie Clark and Ojai obstetrician Dr. Robert Skankey and sustained by visiting doctors and “madrones,” teaching themselves hygiene, pre-natal nutrition and emergency procedures.

None of it would be possible without the determination of Clark, the renowned artist and founder of the Nomad Foundation, a 501c3 organization created to promote and protect the artisans of one of the world’s most remote regions. While the gallery is closing, the foundation will remain active.

The midwife program is only one of many efforts — another is the school at the Tamesna Center, all students are boarders, as their families roam in search of grazing for their livestock. It is the sole educational opportunity for many miles around.

Leslie Clark, rest assured, will stay busy. “I’m ready to retire, to write my memoir, paint more, travel and paint while traveling as I once did,” she said. She and husband Michael are also fixing up a vintage Airstream trailer. “My goal is more creativity and less stress.”

The Tamesna Center for Nomadic Life is a waystation for the Taureg and Wodaabe tribes, who still follow the ancient rhythms of a herding life, following the rains with their livestock from pasture to pasture, chasing forage for their cattle and camels across the Sahel and southern Sahara Desert. The desert may be harsh and inhospitable — temperatures climb past 130 degrees during the summer days, while winter nights regularly drop below freezing — but the cultures created from these conditions are vivid, artistic and resilient.

The Tamesna Center gives them an opportunity to have their children educated while remaining true to their peripatetic culture. The cohort of students are now in junior high school and enrollment has increased to 45. The center also hosts an annual festival of nomadic tribes — with camel races and festivities, which also serve the purpose of informing the nomads about the health and education services available at the center.

The festival has become one of the area’s leading events. The Wodaabe festival participants left a vivid impression on Barbara Bowman, one of dozens of Ojai residents who have traveled to Niger with Clark as a guide. “… I realized we were the only westerners among more than 900 camel-riding nomads. The full moon shone down on us like a spotlight. Drums in the distance drew us to an enormous circle of male dancers, fully made up in yellow and white paint that exaggerated their eyes and teeth, a single feather coming up the back of their braided hair, all moving and stamping their feet to the rhythm of their pounding,” she said.

She also learned that Clark has earned a special place in the hearts of the nomads. “Rapidly moving rhythmically around us, the men were chanting ‘Bimbia,’ a name they had long ago given Leslie, meaning ‘of the dawn.’ I was totally dumbstruck, as though I had been transported back in time.”

The center has also begun an adult education class. The past year, 30 young nomadic men learned the art (and craft) of motorcycle repair. “They are exchanging their camels for the faster-moving motorcycles,” she said. A motorcycle actually costs less than a camel. “But they don’t know how to repair them. After the program, they will have the skills plus basic tools to start a business as motorcycle mechanics.”

CONNECTING THROUGH STORIES

Clark set a lofty goal for herself. “One of my missions in opening the gallery was to show the human side of these ‘exotic’ people — to tell some of their story and introduce them as individuals.” She says the Wodaabe, in particular, love a good story. “When I first stayed among the Wodaabe and tried to learn their language — I never laughed so hard in my life. I rarely heard them argue, but they were always talking and laughing.” They especially love the story of how Clark weathered a storm. She was wrapped like a mummy in plastic tarp, strapped to a folding bed, hoping that someone would remember where she was. “I was suffocating and then the storm blew in with full force, sand and fat drops battering the tarp — me sweating inside … I wondering if anyone would remember to release me from my cocoon. “At last Peroji came and I emerged into the coolest air I had felt in weeks … this incident was recalled for years around the campfire accompanied by hysterical laughter. It still is.”

The nomads love her stories, too. “One of my favorite stories to tell is ‘Romeo and Juliet.’ They love it, but they always insert characters from their own knowledge — often me and one of the many handsome nomads who have proposed marriage. By the nature of their lifestyle, they are obliged to fall in love at first sight — not much time for courting.”

Dr. Skankey witnessed the bond between the fourth-generation Ojai resident and her nomad friends. “I caught a picture of her sitting in a tent with six Wodaabe and Tuareg women all lovingly lying close with their arms around her,” he said.

Her first of more than 50 trips to Niger was inspired by the Carol Beckwith book, “Nomads of Niger,” which came out in 1983. “I found her guide and he took me out to meet my first Wodaabe nomads — the families of (the guide) Peroji became my go-to people for the next 15 years,” Clark said. But it was clear that the best guides for the interior regions Clark sought were Taureg. But the Tuareg were in open revolt against the Niger government and were prohibited from doing business in the country. After the revolt settled down, she found a guide named Mohammed. “His skill in navigating the desert was uncanny … he was the best at his trade, handsome and charming. We worked together for eight years and I helped him start a travel agency — Egarow Voyages which worked in partnership with my own Nomad Adventures.

“He took good care of all of us in the desert, but eventually he stole my car and stopped paying our personnel so that was the end of that.”

Her next guide was Sidi Mamane. “We had a rough start in 2005, stuck up to our ears in mud, broken windows in the car, trying to help in a very serious famine. This same disaster attracted the attention of Rotary Clubs because of widespread media coverage. They continue to fund projects for us.”

In fact, Clark said, Mamane, also the mayor of Agadez, founded a thriving Rotary Club in that part of Niger in 2006, the first in that turbulent region, which was recently shut down because of another rebellion. “He has been to the United States any times at our invitation and was featured on the cover of Ojai Quarterly when he came for the premiere of the documentary, “Roadtrip Niger.” (See Spring 2017 OQ.)

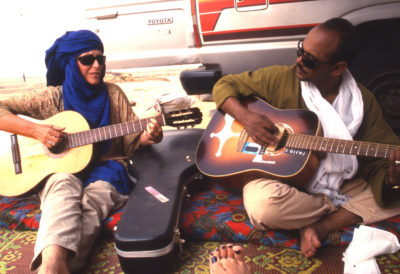

The documentary, produced and directed by Benedicte Schoyen and her husband, Ned Clark, who is also Leslie’s nephew, intended to tell the story about Clark and her foundation, but it quickly became clear it was too big a story for a 70-minute documentary. “So it turned into a travel story about the trials of novice travelers to Niger, their observances of the nomads and the work of the foundation,” Clark said. One of the high points of the entertaining, informative film is Ned Clark, a country-western musician, jamming with the nomads, exchanging melodies and rhythms between two cultures 8,000 miles apart — finding a common language through their guitars, voices and other instruments.

BOMBINO GETS HIS VISA

For the Taureg, music is the language of their rebellion, of their fight for independence. “A whole generation played music — trained as part of the Tuareg rebellion — it was music that brought them together and how they communicated their cause and even where to come to train for the fight,” Clark said. “The culture was illiterate — there were no cell phones, but the clever rebel leader brought guitars — the first Taureg guitarists trained others to play and wrote songs which were sent around on cassettes to remote camps to explain to the nomads what was happening.” It was eventually banned by the government, “which served to make it even more popular,” Clark said.

She has acted as a cultural ambassador, bringing many of these musicians to America. Clark herself got to meet her own icons — Mickey Hart and Bonnie Raitt. At a fundraiser, Tidawt — a group of Taureg musicians including Bombino, Hasso Akotey, Bibi and Anana — were rocking the crowd with their distinctive desert blues, which led to a recording on which world musicians — including Tidawt — recorded Rolling Stones songs in their own style. “Hasso wrote the lyrics in Tamacheq, the Tuareg writing which is one of only two (systems) ever developed on the continent of Africa,” Clark said.

Bombino was the first musician from Niger to be nominated for a Grammy award in March, 2019 — Clark hosted a party for him at her Ojai ranch.

His first trip to the United States went a little differently. He came at the invitation of the Nomad Foundation in 2005. His visa had been turned down by the consul until Clark called to explain that he and his group were going on tour … “He took in his guitar and played — rocked the embassy — the ambassador came in to dance and Bombino got his visa,” Clark said. “He may be the only visa applicant ever to have interviewed for a visa with a guitar.”

As if sporadic fighting and famines weren’t enough for the nomads of Niger, terrorism has shut down their nascent tourism industry. Clark explained that the fall of Moammar Gadhafi in neighboring Libya has created chaos through the region, with widespread smuggling of weapons, and now “destabilization has led to more criminal activity like drugs and human smuggling.”

Without alternative sources of opportunity and money in an area with high youth unemployment, the allure of terror cells or smuggling is strong. “Thus programs like the motorcycle repair training and an ongoing microcredit providing $200 to start small businesses are key,” Clark said.

PAINTING THE PEOPLE

Even with all these enterprises and ventures, Clark continues to paint her distinctive, richly hued portraits of nomads. Bowman has seen that dedication vividly. “She is an artist first. Capturing the faces, dress, jewelry, scenery on canvas was what motivated her from the beginning. Seeing their huge needs, she easily fell into wanting to make a difference in their lives,” she said. “They live simply, often on the edge of starvation, but with a rich community culture that depends on each other.”

While working on her master’s degree thesis at George Washington University, Clark took a year off to travel to the south of France, “I lived there for a year and was asked to have my first show in Monaco, where I sold many of my thesis paintings. That set a pattern for all my painting life. I took a trip, painted my experience and came back to try to sell the paintings to earn enough for the next trip.

Some friends in Ojai, Denzyl Feigelson and Pam Murphy, “badgered me into opening a gallery in partnership. The old Bank of America was renovated and I got the corner spot, which I now feel is the best spot in town.” Enter Norman Rem, who sold Clark’s paintings at his gallery in the Arcade, Artist and Outlaw. When Norman closed the gallery, he joined Leslie as her gallery manager and Nomad Gallery was born in 1996. Norman Rem, then owner of Artist & Outlaw Gallery in the Arcade, had been selling Clark’s nomad paintings, and he was about to close the gallery to help raise his son.

She talked him into managing her gallery, and he’s been there ever since. “Leslie always has wonderful stories to tell about the pieces and how she came to acquire it. It was a history and a geography lesson and never dull,” Rem said.

On her fourth trip to Niger in 1997, Clark bought a cow for a nomad. When she returned the next year, she saw the huge difference the modest gift had made for the family. “They were able to remain nomadic herders — the only skill and life they had ever known — instead of moving to the city,” she said. Because of these simple, unmet needs, Clark started under the umbrella of the WILD Foundation before establishing her own nonprofit group in 2005.

DANGER ZONES

Clark is drawn again and again to Niger despite the many perils. “On my first trip, I got caught in a tribal war in Ghana and had a bow and arrow pointed at my face,” she said. “Several years later, I groveled in the cold sand, hiding behind a bush listening to shots from AK-47s as bandits threatened everybody in my group of tourists … I didn’t know if those bullets were killing someone.”

There’s a poetry to the remoteness, the isolated splendor of being so far off the grid, Clark said. “It’s fantastic.” There have been incidents, though such as September 2001. “The only way to call home is to wait in a telecentre, wait sometimes hours for a connection to go through and pay $50 to $100 for a call of less than 10 minutes. This was the situation when I learned about 9-11 and I miraculously was able to get through in only an hour — I found out my family was well, but I could not leave Niger as there were no planes flying.” She stayed with her Wodaabe hosts, who wondered “if the bad guys flying the planes were all dead, what was the problem?”

Another misinterpretation happened when her Wodaabe hosts came running up with their transistor radios broadcasting the BBC in the Hausa language to warn Clark that a war had broken out in the United States. She didn’t understand the language, but she did hear the words “Mike Tyson” and “Las Vegas” and figured out that it was a big boxing match. “The Wodaabe use the same word for fight as for war — their battles being on a much smaller scale than ours.”

Clark has hosted dozens of Ojai residents, including members of the Rotary Club of Ojai, on trips deep into Niger.

Leslie Clark has brought dozens of people to Niger, including many Ojai residents — Amanda McBroom, Barbara Bowman, Bob Davis, Linda Taylor and others. She has also brought many Niger residents to Ojai, including the Tidwayt musical group, which recorded with jazz legend and Ojai resident Roger Kellaway. The distinguished guests also included Sidi Mamane, mayor of Ingall, and Boucha Mohamed, Niger’s Minister of Agriculture.

Ojai’s Jill Townsend was asked by Clark to make a trip in 2006 for relief efforts after a severe drought. “She told me, ‘We have to go and make sure these rebuilt wells are working. Are you coming?’

“It was an extraordinary trip; one month, 1,800 miles traveling with the Taureg across the desert, carrying our own water, sleeping on the sand, no toilets, no modern conveniences of any sort,” Townsend said. “It was amazing. Every second. Leslie has gifted us with the challenge and opportunity to help an ancient people keep their culture and survive. Aman Iman. Water is life.”

The two main nomadic tribes in the region — Taureg and Wodaabe — are both herders and fiercely proud of their cultures. But their differences, Clark said, can be neatly summed up by the way they describe each other. “The Tuareg think the Wodaabe are magicians and shape-shifters. The Wodaabe think the Tuareg are thieves. Both have an element of truth.”

As Clark winds down the Nomad Gallery after 23 years, the occasion will be marked. On June 21, the monthly Third Friday event with downtown merchants, “we will be open late, with increasingly lower prices. The Third Saturdays will be patio sales to benefit the foundation as we have done for 20 years. And our closing party will be a concert on June 21 with Karyn 805 performing on the patio, followed by the final patio sale on June 22.”

Clark will continue to paint — Human Arts Gallery will represent her work. It won’t be the same for some collectors, such as Paul Finkel of Westlake Village. “Visiting Nomad over the past 15-plus years was always exciting and great fun. It allowed us to bring to our home a small but beautiful part of African Art and culture. And I have so enjoyed the longstanding friendship with Leslie that was both meaningful and inspirational.”

Someday, maybe after her memoir is published, Clark would love to have a retrospective at the Ojai Valley Museum, which would feature her colorful family history, four generations in Ojai, plus her own work as an artist. “I would bring some Tuareg musicians and jewelers for that since they feel the connection between Ojai and the nomads — but that is only a fantasy — I haven’t been invited.” ≈OQ≈

Leave A Comment