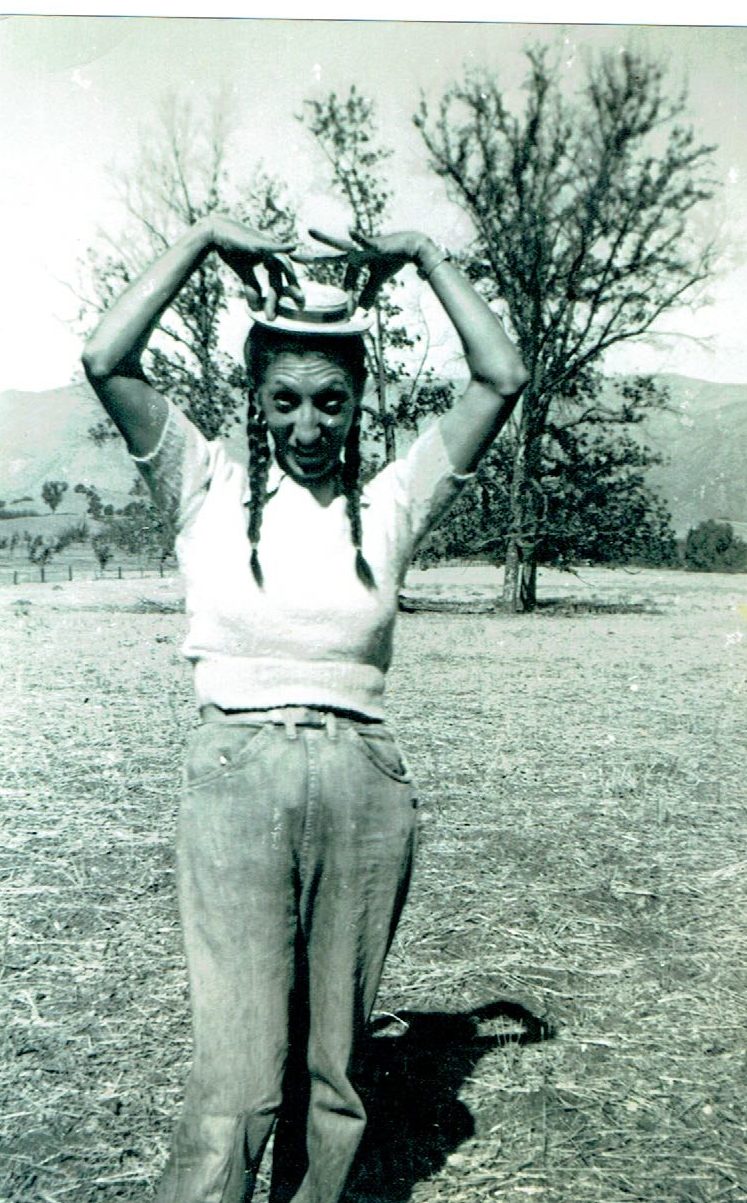

Blanche Kroll, Ojais Postmistress in the 1950s, who was subject to an FBI investigation because of her subscription to a left-leaning publication.

By Michael Kroll

McCarthyism Goes Postal

It was still dark one very early morning, too early for work or school, when I awoke to see my mother standing just inside the open door of the bathroom across the hall from the screened in service porch where my brother and I slept. She was standing in front of the mirror, so her back was to me. I don’t know why I didn’t go back to sleep, but instead got out of bed. It was cold, and I could see my breath, so I wrapped myself in a blanket, and stepped barefoot into the bathroom. Mommy was engaged in a morning ritual, which she described as “putting on my face.” I loved watching her do this, but there was something different about it this morning. Her eyes were red-rimmed and her mouth was set in a way I hadn’t seen before

“What’s wrong?” I asked. She continued putting on her make-up, but answered, “Nothing. Go back to bed.”

“Why are you going to work so early?” I asked. “Are you crying?”

“I’m not going to work today, Honey,” she explained. “I have to go to Los Angeles.”

In those pre-freeway days, Los Angeles was at least a two-hour drive from Ojai, one which we made once or twice a year to see grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins on my father’s side.

Seeing how sad my mother looked that morning brought me close to tears. “Can I go with you?” I asked. “Is Daddy going?”

“No, Honey,” she said, as gently as she could. “This is something I have to do by myself. Daddy has to go to work, and you have school today. Go back to bed.”

“But I want to go with you,” I begged. I’m not sure why it was so important to me, but I wanted to be with her, to help her through whatever it was that was making her cry.

It’s a given that we are, in part at least, reflections of our times and our place within those times. Which means that our parents’ time and place is also ours, not just in the overlap of time we shared, but in the memories of their stories, second-hand memories of one’s own times as told by those who remember.

I was six years old and in the first grade in 1950, so some of what I am about to describe comes from those stories; much comes by way of official government documents.

It was a time of government witch-hunts. Smack in the middle of the last century, a Wisconsin Republican, Senator Joe McCarthy, was making a name for himself by hunting down government employees he accused of being Communists, then the avatar of the enemy that America’s strains of nativisim and xenophobia have found throughout our history. From the Alien and Sedition Act of the 18th Century to the Chinese Exclusion Act of the 19th Century, and through the then-recent national shame of interning Americans of Japanese ancestry, America’s history of burning witches, literally and figuratively, has run parallel to and alongside such nobler ideals as “equal justice under law.”

More than half a century has passed since the passing of those “scoundrel times,” as writer Lillian Hellman characterized them. To most Americans, perhaps, this era is associated with those in the top tier of society. Richard Nixon defeated California Congresswoman Helen Douglas in 1950 by branding her “the Pink Lady — pink right down to her underwear.” The House Un-American Activities Committee targeted liberal Hollywood writers and actors, hauling them before Committee hearings to “name names” or face a blacklist that devastated their careers.

They searched for Communists in the State Department; they searched for Communists among university faculty and staff; they searched for Communists in the military; they searched for Communists in Hollywood. But the poison seeped down into the most mundane of professions, the most mundane of places, like the Ojai Valley post office where my mother, Blanche Kroll, was employed — a post office which served a population of 2,519 according to the 1950 census.

What is often overlooked in the historical memory is how this national witch hunt affected ordinary people, people who were not famous, people who were living in small towns as well as large cities, people no one ever heard of, people with the most tenuous connection to the government — people like my mother, a 34-year-old woman raising three young children with her husband, working then as a roofer, but in transition to the less strenuous job of Sears salesman. She had, in 1948, been appointed to the exalted position of “substitute rural carrier,” a step up from the Sweet Shop, a soda fountain she had been running in the middle of the graceful Ojai Arcade that defines one side of the main thoroughfare through town. My own memories of that place flit in and out of my mind like hummingbirds — me sitting on a counter stool eating ice cream while my mother moves up and down behind the counter pouring coffee and talking with one patron and then another.

Now, two years after she moved from the Sweet Shop to the post office, we moved from the Lower Valley into a ramshackle ranch in the Upper Ojai. That move came about when another “mail lady,” as we called them, Helen Robinson, asked her fellow postal workers if they knew of anyone who would want to live there rent free in exchange for keeping it up. Reputed to be the oldest female mail carrier in the country, she had been living alone in the old place. My mother did not hesitate. “Yes,” she answered. “Me!” And so we moved.

My memories of the post office are clearer than those of the Sweet Shop. I remember the big swinging doors in the back. I remember the letter-cancelling machine behind the gated windows where Garnett and Bernice sold stamps. That machine clacked away as hundreds of letters sped through it to be cancelled, prompting a lecture from Mom, who introduced me to Bernice, and told me the story of how she had mangled her fingers in that machine. I didn’t go near it. I even have a vague memory of accompanying my mother on her delivery route along Creek Road, where she told me that one of the mailboxes was home to a black widow spider in the back, causing her to place the mail in that box very gingerly.

On that cold morning when I asked my mother what was wrong, she had then only the vaguest idea of what was happening. She told me later, when she thought I was old enough to understand, that a very nasty man had loudly labeled her a Communist, both in letters he wrote to the postmaster, and by yelling it on the street whenever he saw her. That had led to an ongoing FBI investigation, which in turn had led to the internal security hearing she was ordered to attend that morning in Los Angeles. But since then, I have obtained the records maintained by the Civil Service Commission and the FBI, and so I know both the details of the government’s investigation into my mother’s loyalty, and of the ensuing internal security hearing for which she was getting ready.

The “nasty man” is identified in those records as “Mr. William Swanson, the original complainant.” It is not a name I remember ever having heard. His first “complaint” went to my mother’s boss, Assistant Postmaster George Busch. It accused her of being “a member of the Communist Party,” (she wasn’t), and that “she holds Communist Party meetings at her home,” (she didn’t). He tried to put a paid advertisement in the Ojai newspaper stating that the Ojai post office was employing “an avowed Communist,” but the paper refused to take the ad.

These accusations did not go unnoticed at the highest levels of government. On January 17, 1950 — less than a week before my mother’s 33rd birthday — FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover ordered his FBI agents “to conduct a full field investigation of the captioned individual reported to be a member of the Independent Progressive Party of California and to have circulated petitions to put the Independent Progressive Party on the California election ballot.”

In his first response to Swanson’s very loud and public accusations, Assistant Postmaster Busch, whose wife was my first grade teacher, told FBI investigators that “he had no reason to question her loyalty,” though he acknowledged that she sported a “Wallace for President” button during the presidential campaign of 1948. Former Vice-President Henry Wallace headed the Independent Progressive Party that year, one of four parties vying for the presidency. In addition to the Democrats, led by incumbent President Harry Truman and the Republicans led by New York Governor Thomas Dewey, there was also the segregationist Dixiecrat Party led by South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond.

It was my mother’s commitment to the Wallace campaign and the progressive principles it stood for that formed the basis of Swanson’s belief that she was a Communist, but it was not the only basis. In March, 1950, he told Owen W. Malcolm, the FBI agent who questioned him, that “she holds meetings in her home attended by left wing writers and actors from the movie industry,” adding that he had “seen Mrs. Kroll in the company of CHARLIE CHAPLIN (sic),” and that she sold tickets “to the Paul Robeson concert held in Los Angeles about six months ago.” Agent Malcolm noted that “Swanson offered no proof of his allegations,” and described him as “the type of person to exaggerate things… therefore his statements could not always be relied upon.”

Surprisingly — or maybe not so surprisingly — the FBI failed to note (or to reveal) that Mr. Swanson had made the front pages of the Los Angeles Times a few years earlier when a jury found him guilty of indecency as the producer of an “an indecent show” called “White Cargo.” (See Los Angeles Times, January 24, 1941)

While the FBI apparently missed this revealing tidbit, journalist Mark Lewis, whose pieces have appeared often in these pages, did not. In a long article tracing the history of the Ojai Theater (“The Century of Cinema: Ojai’s Lasting Picture Show,” March 18, 2014), Lewis identified William Swanson as having owned the theater during the 1930s. In addition to the indecency conviction, Lewis cites a source who told him that Swanson privately screened pornographic movies at the Ojai Theater for selected male audiences. Being both tactful and generous, Lewis described Swanson as “Ojai’s own P.T. Barnum.”

Of course, there were gatherings of actors in our house. My parents had helped to found the Ojai Valley Work Shop, a theatrical group that produced plays in which both my parents acted. The closest our house came to hosting a movie star was when Hurd Hatfield joined the little theater group. Among his Hollywood credits, in 1945, he played the title role in Oscar Wilde’s “The Picture of Dorian Grey.” Lamentably, Charlie Chaplin was not among our visitors. Though it is reliably reported that the great screen clown did visit Ojai, I regret that my parents were not among those he visited.

Besides Swanson, the FBI interviewed many friends and acquaintances of my parents in their full-field investigation of my mother. A number of witnesses focused on what they often described as “secret meetings.” Its members, in the words of one witness, Betty Eddy, “were very strong supporters of the Independent Progressive Party in 1948, and they were all in favor of its policies which purported to be beneficial to the working class.” In her opinion, “they were bitter and disgruntled over their station in life and were seeking an outlet for frustration.” She identified twelve members of the group, of whom I personally remember seven, all wonderful family friends. While telling the FBI that “there is considerable talk in Ojai to the effect that this group is Communistic,” she also told them that she “never observed or heard anything which was of a disloyal nature.”

The Chaplin lie seems funny in retrospect, but other lies were not so benign. One witness told the FBI that “Mrs. Kroll has a picture of Stalin in her living quarters,” though he acknowledged that he had never been in her home. That same witness also alleged that his own mother had heard my mother “making a statement to the effect that she would like to see the United States government overthrown by force.” But when the FBI later questioned the woman, she told them she did not know my mother, and “had no information concerning her.”

One witness claimed to have known my mother since 1929, though he failed to note that she would have been just twelve years old at the time. He claimed that she and my father had been active in “a youth organization” in college whose name he could not remember, but which he believed was “Communistic” because “she had told me of its activities in developing equality of all people.” The only student group my mother actually belonged to when she attended Los Angeles Junior College in 1935, according to the government documents, was the Menorah Society, described as “a Jewish social club.”

A fellow postal employee, Joe Potts, recalled that “on one occasion, I heard her accused of being a Communist, at which time she did not take offense and did not offer a denial.” Pott’s boss, the Assistant Postmaste,r who had told the FBI he had no reason to question my mother’s loyalty, now “advised that he noticed that Mrs. Kroll received the publication Daily People’s World during the month of November, 1949,” though he couldn’t be sure she was the subscriber. In fact, it was my father’s subscription. An “internal Security” letter from the San Francisco office of the FBI noted that “on August 21, 1948, Max Kroll contributed $10 for the People’s World’s sustaining fund drive.”

As the investigation dragged on, Hoover sent at least two more memos to his field offices in Los Angeles and San Francisco castigating them for not completing the “loyalty investigation” by the deadline he had prescribed, and ordering them “to immediately submit a report.”

That both my parents were active in the new Independent Progressive Party is a theme that runs throughout the nearly 100 pages of that report, which notes that “appointee and her husband changed their party preference to Independent Progressive Party on April 12, 1948,” adding the detail that “Blanche Kroll, 415 Grand Avenue, Ojai, California, had circulated a petition to place Independent Progressive Party on the ballot in 1948.”

In a section of the report captioned “Results of Investigation,” the FBI notes that “the Independent Progressive Party was cited by the House Un-American Activities Committee in its report of 1948 as “among typical mass organizations that are victims of Communist domination.”

Reading the huge Progressive Party platform now, I am not only proud of my parents’ active support, but also astonished at how much of what they called for 65 years ago remains relevant today.

“Never before have so few owned so much at the expense of so many,” the platform begins. It characterizes both the Democrats and the Republicans as “champions of Big Business.” It accuses both major parties of blocking “national health legislation even though millions of men, women, and children are without adequate medical care,” and asserts “the right of every American to good health through a national health system.” It “condemns segregation and discrimination in all its forms and in all places.” It calls for “a Constitutional amendment that will effectively prohibit every form of discrimination against women — economic, educational, legal, and political.” It called for working through the recently established United Nations “for a world disarmament agreement to outlaw the atomic bomb, bacteriological warfare, and all other instruments of mass destruction.” It “urged that all general and primary election days be declared holidays to enable all citizens to vote, and the full use of Federal enforcement powers to assure free-exercise of the right to franchise.”

Other planks in the platform read more like idealistic pie-in-the-sky. They demanded that the government “guarantee the right of every family to a decent home at a price it can afford to pay.” They declared it an “inalienable right to a good education to every man, woman, and child in America.”

Citing the internment of American citizens during the War, the platform recognized “the just claims of the Japanese-Americans for indemnity for the losses suffered during wartime internment, which was an outrageous violation of our fundamental concepts of justice.”

Many of the planks in the Independent Party platform have since been achieved. Among other things, they called for:

… the principle of self-determination for the peoples of Africa, Asia, the West Indies, and other colonial areas;

… the immediate passage of anti-poll tax legislation;

… the abolition of Jim Crow in the armed forces;

… the creation of a Department of Education with a Secretary of Cabinet rank;

… the abolition of the House Un-American Activities Committee and similar State Committees.”

Ironically — or, perhaps, presciently — the platform demanded “that the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other Government agencies desist from investigating or interfering with the political beliefs and lawful activities of Americans.”

I was just five years old when these principles were proclaimed in the Independent Progressive Party platform, and though I am now 71, I still feel inordinate pride in my parents’ commitment to them. But that cold morning in 1950, as my mother prepared to face a government panel armed with secret accusations against her, I felt nothing but confusion and fear. As afraid as I could see that she was, she acquitted herself well, according to the transcript of that hearing. When the not-so-grand inquisitors named one of her friends as a “card-carrying Communist,” and asked if she would continue to allow this friend into her home, my mother said that she knew the labels they had attached to her were lies, so she had no reason to believe the label they attached to her friend. When they “informed” her that my father, her husband, subscribed to the People’s World and asked if she would continue to permit the publication in her home, she told them that she had never censored what he could read, and she had no intention of starting now.

J.B. Tietz, the attorney the ACLU provided her at that hearing, asked her a number of questions about the Indian philosopher and teacher, J. Krishnamurti, who lived and lectured in Ojai about six months out of the year. But each time his name came up, it was transcribed as “Christian murder.”

Question: “Do you follow the teachings of Christian murder?”

Answer: “Well, I don’t understand all of it, but what I do understand, I apply some of it to my life, and some of it I don’t.”

This dark period left a legacy in the country’s history as well as in the history of my family. The country moved into the tumultuous decade of the 1960s, much of it a vocal, in-your-face reaction from young people against the repressive era their parents had lived through.

My mother did not participate in the fervor of the ‘60s. Her political idealism had been crushed, leaving her cynical to the benefits of political dissent. Her postal career ended with the third and final statement to the FBI by the Assistant Post Master. In an item dated March 10, 1950, “Busch stated he is taking it upon himself to correct this situation by not giving Mrs. Kroll any more work.” I finally understood why, at the end, she asked only that her ashes not be scattered in Ojai.

My brother, sister and I each paid a price.

In 1965, having recently returned from a year-long trek through Africa, playing the guitar and singing folk songs to earn his way, my older brother organized a slide show of his travels to show at Nordhoff, our former high school. The travelogue-concert combination was immediately attacked as an attempt to present left-wing propaganda. At a public meeting in the high school auditorium where my brother had to defend the program as non-political, my father later told me that he overheard a man in the row in front of him telling his wife, “He caused all that trouble at Berkeley and now he wants to spew his ideas here.” At that point, my father leaned forward, tapped the man on the shoulder, and, through clenched teeth, advised him, “That was my other son.” In a reversal of fortune that may also reflect a more positive legacy, the good people of Ojai voted to allow the slide show to proceed.

At about the same time, my younger sister was deeply involved with a young man who told her that he had heard that her brothers were Communists. When he told her to choose, she did. Their relationship ended.

As for me, I joined the Peace Corps in 1965 immediately after graduating from U.C. Berkeley, still on probation from my recent arrest in the Free Speech Movement. On the last night of our three-month training at the University of Northern Illinois, I received a phone call informing me that I had been assigned the status of “political hold” three months earlier, and that the next morning, when my fellow volunteers boarded their plane to Hawaii for practice teaching, I alone would board a different plane bound for Washington, D.C. to answer questions. I did not know if I would ever join them again, either in Hawaii or at our final destination, Malaysia.

When I arrived at Peace Corps headquarters, the two Civil Service Commissioners assigned to question me told me that the investigation was prompted by an informant who had (erroneously) reported that I had visited Cuba in 1962 during a summer trip to Mexico. But when I examined my own FBI records decades later, what I read on the very first page belied that assertion. The Civil Service Commission had referred my Peace Corps investigation to the FBI, “based on information contained in FBI reports pertaining to subject’s mother, Blanche Edwina Kroll, CSC Security Files and CSC report of investigation at Berkeley, California, pertaining to subject’s associates and organization affiliations, all of which raises a possible question of loyalty.”

Whatever “loyalty” demands, I know this: the objectives of an egalitarian society that my parents fought for are as desperately needed today as they were more than half a century ago when the events I’ve described here occurred. I have to ask myself what loyalty means in an age when my government is engaged in massive spying on its own citizens. Ought I to be loyal in an era during which government services to the most vulnerable — the poor, the young, the elderly — are being slashed in the interests of the top one or two percent of the population whose wealth continues to grow? Should I be loyal to a Supreme Court which gives corporations the same First Amendment rights as individual citizens, or which has eviscerated laws that Congress passed to protect minority voting rights, or which continues to narrow access to public education by racial minorities? What loyalty do I owe my government, engaged as it is in perpetual warfare? Should I be loyal to a government that continues the practice of subjecting a handful of its citizens enslaved in the largest prison-industrial complex in the world, to the final solution of capital punishment?

My own views, perhaps, can best be expressed by one of my mother’s accusers, Allan Kempke, Jr., who told the FBI that my mother had said, “What this country needs is a good revolution.” According to what my mother later told me, she was only slightly misquoted. What she actually said was, “What this country needs is a good five-cent revolution.” Adjusted for inflation, it is a sentiment with which I heartily concur.

Michael Kroll is a widely-published award-winning journalist specializing in criminal and juvenile justice. He was the first director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, D.C. He lives in Oakland with his partner and his two dogs.

Leave A Comment