By Mark Lewis

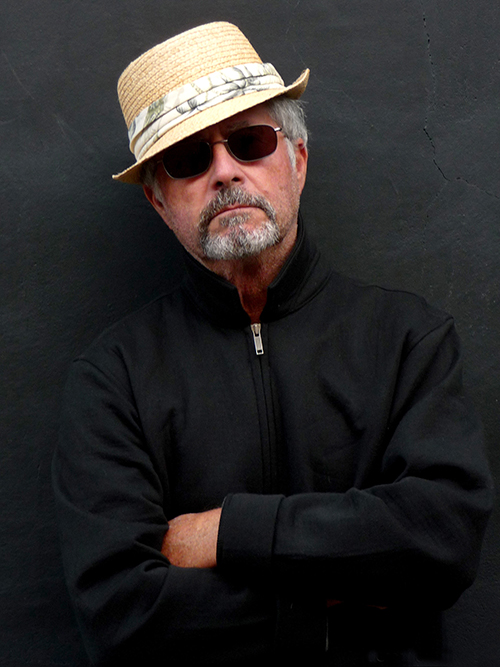

For 75 years, the legendary photographer Guy Webster led a charmed existence. Then health problems laid him low, to the point where he could no longer operate a camera or ride his beloved motorcycles. Now he is willing himself toward recovery, and cultivating a philosophical detachment toward what he has lost, and reveling in the richness of what remains: his family, his friends, and his memories of a truly extraordinary life.

Ojai has no shortage of raconteurs, but Guy Webster is in a class by himself. Walk by NoSo Vita in the morning and you’ll likely see him sitting there with a cup of coffee in his hand, holding forth for a table full of friends. Drop by the Porch Gallery on a Saturday evening to attend an art opening and there he’ll be, sitting on the veranda at the center of a group that is hanging on his every word. And he drew a big crowd on Aug. 14 at the Ojai Valley Museum to hear him talk about his world-famous collection of classic Italian motorcycles, five of which were on glorious display in the background.

Over time, this collection has totalled more than 350 bikes, but Guy has sold most of them off. Since suffering a stroke in April 2015, he walks with difficulty and he can’t ride at all. Embracing the rehabilitation challenge, he took himself from wheelchair to walker to cane. More recently he took a tumble that has set back his recovery process, but he still maintains a hectic travel schedule, and when in town he still makes the rounds. On the eve of his 77th birthday, he sat down with the Ojai Quarterly to reminisce about his life and career.

TINSELTOWN TEEN

Guy Webster made his Hollywood debut at the age of 1 in November 1940, appearing in the hit film “You’ll Find Out,” which starred the popular bandleader Kay Kayser. The supporting cast included Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre and Bela Lugosi. According to the Internet Movie Database, Guy was cast as “an infant.” No screen credit, alas. But he did have one laugh line, of sorts: When someone asked him what he thought of Adolf Hitler, he stuck out his tongue and blew Hitler the raspberry.

“My father trained me to do that,” he says.

What had brought little Guy to a sound stage at such a tender age? Blame it on another child actor, Shirley Temple. Several years earlier, the Fox studio had lured Guy’s father, the lyricist Paul Francis Webster, west from New York to write songs for Temple, then the biggest star in the world. Paul apparently only wrote one lyric for her – a lullaby she sang to her doll in “Our Little Girl” (1935). But he found Southern California very much to his liking, so he settled in Beverly Hills and became one of the movie industry’s most successful lyricists. Guy’s own film career ended where it began with “You’ll Find Out,” but his father went on to garner 16 Oscar nominations and three wins during his four-decade Hollywood career.

Working with such legendary composers as Hoagy Carmichael and Duke Ellington, Paul Webster wrote the words for many hit songs, at least three of which are now considered standards — “I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good)” and “Black Coffee,” both composed by Ellington, and “The Shadow of Your Smile,” composed by Johnny Mandel.

Hits were nice, but it was Paul’s film work, mostly for MGM, which financed his Beverly Hills lifestyle. He installed his family — wife Gloria, sons Guy and Roger — in a handsome, three-story Tudor Revival house on North Crescent Drive near the Beverly Hills Hotel. Still, everything is relative, even in Beverly Hills.

“I thought we were poor because we didn’t have a tennis court,” Guy says.

Guy was a serious-enough tennis player at Beverly Hills High School that he came up here to play in The Ojai Tennis Tournament — his first exposure to his future home. But sports heroes did not inspire awe in Beverly Hills, where Guy’s peer group included many children of Hollywood celebrities who were also future stars themselves: Edgar Bergen’s daughter Candice, Danny Thomas’s daughter Marlo, Frank Sinatra’s daughter Nancy, Judy Garland’s daughter Liza Minnelli. Guy’s good friends included Terry Melcher, whose mother, Doris Day, had sung Paul Webster’s Oscar-winning song “Secret Love” in the 1953 film “Calamity Jane.”

This sounds like a glamorous childhood, but Guy says it left him prematurely jaded, because it exposed him and his friends to the seamy side of their parents’ Hollywood lifestyle. This was during the “L.A. Confidential” 1950s, a time when Lana Turner’s teenage daughter Cheryl Crane came home to Beverly Hills from Ojai’s Happy Valley School for spring break in 1958 and stabbed her mother’s gangster lover Johnny Stompanato to death, in what was ruled a justifiable homicide. That’s an extreme example, but Guy and his friends saw things that did not square with the picture-perfect Hollywood image.

“We knew what was going on,” he says. “It shocked us. We saw it all. I didn’t like it.”

He escaped first to Whittier College and then, as a foreign-exchange student, to Copenhagen, where he hung around with “highly intelligent people” who were artistic rather than materialistic.

“It seemed like a respite for me to be away from the over-abundant life in Beverly Hills,” he says.

A political science major, he admired John F. Kennedy and planned to go into politics. But a short stint in the Army during the early 1960s diverted him into photography. His superiors at Fort Ord asked him to teach some of his fellow soldiers how to use a camera. He had never used one before, but he read some photography books and bluffed his way through, and found that he had real talent.

“I went nuts for it,” he says.

He had planned to attend grad school at Yale after he left the Army, but instead ended up at the Art Center College in Los Angeles, with the goal of becoming a fine-arts photographer who would show his work in galleries. And so he would — eventually. But first he had to make a living, and that led him to Hollywood.

Guy’s father did not approve of his career choice, and declined to fund it.

“He thought I’d be a paparazzo,” Guy says. “He cut me off financially at a very early age.”

So Guy started working for the many record companies based in Los Angeles. He already had connections in the industry, including his old friend Terry Melcher.

This was 1963, when the pop charts were still dominated by teen-idol types who were crooners rather than rockers. The labels offered Guy plenty of work shooting Hollywood-style portraits of popular young singers like Wayne Newton — and Johnny Mathis, who had scored hits with several Paul Francis Webster songs, including “The Twelfth of Never.” But Guy was more in tune with people like Melcher who were more into rock ‘n’ roll.

As a singer, Melcher comprised half of Bruce and Terry, a vocal duo he had formed with the future Beach Boy Bruce Johnston. As a songwriter and a record producer, Melcher had his own company, T.M. Music. Despite its name, T.M. was dominated, not by Melcher, but by his high-profile business partner, the singer Bobby Darin. Melcher connected Guy with Darin, and as a result, Guy ended up photographing Darin for Capitol Records. It turned out that Guy’s then wife, Bettie, was good friends with Darin’s then wife, the movie star Sandra Dee, so the two couples began socializing together.

Darin personified the changes that were in the air. He had started out in ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll (“Splish Splash”), then segued into his Sinatra mode (“Mack the Knife”), and was now exploring new sounds — not only country and folk, but also surf music and its subset, hot rod rock. The Beach Boys and Jan and Dean currently were scoring hits in this genre, so Darin and Melcher decided to try their hand at it. They co-wrote “Hot Rod USA,” which Melcher then put on an album he and Johnston were co-producing called “Three Window Coupe.” (Any conceptual resemblance to the Beach Boys’ “Little Deuce Coupe” was entirely not coincidental.)

“Three Window Coupe” was credited to a group called the Rip Chords, although Melcher and Johnston apparently did most of the singing in the recording studio, and the L.A. session players known as the Wrecking Crew provided the music. Having recorded the album, Melcher needed an eye-catching sleeve for it, so naturally he called his friend Guy. The resulting cover shot featured a hot-rodded Ford V8 parked incongruously on a beach, garnished with a surfboard and the putative Rip Chords, ogling a comely young lady in a bikini.

“Columbia Records loved it,” Guy recalls.

This was his first album cover. Little did he realize that this would be the format where he would make his biggest mark on the culture.

Like Bobby Darin, Guy straddled the fault line between the glamorous Hollywood of the ‘50s and the trippy counterculture of the ‘60s. He would make the scene at the Whiskey a Go Go, a new discotheque on the Sunset Strip, where rockers like Johnny Rivers ruled the roost; but he also frequented the old-school Cocoanut Grove nightclub on Wilshire Boulevard, where he had been introduced to Bettie on a night when he was there with “Moon River” and “Pink Panther” composer Henry Mancini, a family friend. The 1960-64 period represented an overlap between these two eras, and Guy had a foot in each camp.

Nevertheless, he saw where things were heading. The new generation was getting ready to take over, and he would be on hand with his camera to record the transition. But nobody yet knew how cataclysmic this particular transition would turn out to be.

COVER BOY

The Rip Chords’ biggest hit single was “Hey, Little Cobra,” with Terry Melcher, uncredited, on lead vocal. It peaked at No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart on Feb. 8, 1964. One day later, the Beatles made their first appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” and the world changed, practically overnight. When the Beatles played the Hollywood Bowl in August, Guy was there, looking on from a premium box as a guest of the elderly gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, of all people. She scored the tickets, but he brought the credibility.

“I was the hot photographer in the music business, and so she invited me to come with her,” he says.

Guy couldn’t hear much music that night, due to all the screaming by the teenage girls in the audience. But he could see everything quite clearly, and he knew he was looking at the future. Hot rod rock soon went the way of the Dodo, and “Three Window Coupe” made no headway on the album charts, suddenly dominated by British Invasion groups. But American rockers would soon regroup, with help from a new wave of hip, young producers, one of whom would turn out to be Terry Melcher.

Doris Day was still the biggest female movie star in America in 1964, but her son’s contributions to mid-1960s culture would prove more enduring. Now a full-time producer at Columbia, Melcher had moved on from the Rip Chords to Paul Revere and the Raiders. Then he took on a new group called the Byrds, and produced their cover of a not-yet-released Bob Dylan song, “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The single shot up to No. 1 in the spring of 1965, establishing folk rock as an alternative to British Invasion rock. For a time, the Byrds were hailed as America’s answer to the Beatles, and Melcher was the producer with the golden touch.

That summer, Melcher introduced Guy to another young producer, Lou Adler, who had just founded Dunhill Records. Adler asked Guy to shoot the cover for a new Dunhill album, “Eve of Destruction,” by a little-known singer named Barry McGuire. Guy posed McGuire in a manhole and shot him in black and white, to create a dramatic, gritty-looking image to go with the title song. Released as a single, it went to No. 1 during that epochal summer of ‘65, when rock ‘n’ roll matured into rock music, and “the Sixties” finally kicked into gear.

That fall, when it came time to produce the Byrds’ follow-up album to “Mr. Tambourine Man,” Melcher hired Guy to shoot the cover. Guy’s evocative, arty creation for “Turn! Turn! Turn!” earned him his first Grammy nomination.

People today much under the age of 40 cannot conceive how important album art was in the pre-digital era, and especially in the vinyl era, when LPs were physically big enough to give photographers and art directors scope for their creativity. Their work had a huge impact, because album buyers would hold the sleeves in their hands and stare at the cover while the music played in the background. This was a new art form, and a relatively short-lived one, much like the MTV music video of the 1980s. But album art was a very big deal in its day, and especially in the ‘60s, when the rock audience went supernova.

Chart-topping albums that might once have sold thousands of copies now sold in the millions, and every copy was a visual showcase for photographers like Guy Webster. Rock fans took their music very seriously as an art form, which meant that the album covers must be art too, and the people who created those covers must be artists. And so they were.

“Turn! Turn! Turn!” was just the beginning. That same fall, Guy created at least three other covers that remain iconic today.

For Dunhill, Lou Adler asked him to shoot the cover for the first album by a new group, The Mamas and the Papas. During the shoot in the group’s Laurel Canyon house, everyone got high together, to the point where Guy was no longer very steady on his feet. This was not the way he usually worked, but on this particular day it worked out well. When all four members of the group crowded into the bathroom at one point, inspiration struck.

“I said, ‘I’ve got it — get into the bathtub,’ “ Guy says. “I put the camera on a tripod because I couldn’t hold it.”

The resulting shot — John Phillips, Cass Elliot and Denny Doherty sitting in the tub, with lovely Michelle Phillips recumbent upon their laps — became the eye-catching cover image for “If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears,” the 1966 album that featured the monster hits “California Dreamin’ ” and “Monday Monday.”

Meanwhile, Adler introduced Guy to the Rolling Stones’ manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, who told him that the Stones would be in L.A. soon to record their album “Aftermath.” Would Guy like to shoot them? Yes he would, and shortly thereafter he found himself escorting Mick, Keith & Co. up into Franklin Canyon north of Beverly Hills for a photo shoot near a reservoir. One of these shots, featuring Brian Jones in vivid red corduroys in the foreground, provided the cover for the Stones’ 1966 album “Big Hits (Green Grass and High Tide),” while portrait shots from a later session in Guy’s studio ended up on the cover of their 1967 album “Flowers.”

Then there was Simon and Garfunkel. Columbia assigned Guy to photograph this up-and-coming duo for the cover of their second album, “Sounds of Silence.” He took them up to Franklin Canyon and captured the image that still endures: two young troubadours on a country road, looking back at the camera as they head uphill toward parts unknown.

After the shoot, Guy brought Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel home to meet his parents, and Simon brought his guitar from his car and played the album’s title song for Guy’s songwriter father, who loved it.

One might assume that by this point in the ‘60s, Paul Francis Webster’s day was done. Wrong. Paul won his third Oscar in 1966 for co-writing “The Shadow of Your Smile,” which also won the Grammy for Song of the Year, beating out the Beatles and “Yesterday.”

Around this time, Paul was hired to write the lyrics for the theme song of a new animated TV show, “Spider-Man.” Ever versatile, he came up with lines that would soon be imprinted on millions of young brains: “Spider-Man, Spider-Man, does whatever a spider can.”

In 1967, both Paul and Guy were nominated for Grammys: Paul for Song of the Year for “Somewhere, My Love,” set to the tune of “Lara’s Theme” from “Dr. Zhivago;” Guy for the “Turn! Turn! Turn!” cover photograph. Neither Webster won that year, but both continued to thrive. Paul remained a successful songwriter well into the ‘70s, outlasting the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas and Simon and Garfunkel. He died in 1984.

(For those who are keeping count, in addition to “Secret Love,” Paul’s other Oscar win was for “Love is a Many Splendored Thing” in 1955.)

GO-TO GUY

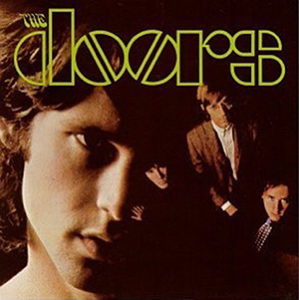

Jim Morrison and the Doors album cover, photograph by Guy Webster

By 1966, Guy Webster had established himself as a go-to guy for every record company in Hollywood, so it was hardly a surprise that fall when Jac Holzman of Elektra Records hired him to create the cover for the debut album by a new group Holzman had signed. What was a surprise, at least for Guy, was that when the band showed up at his studio for the shoot, the lead singer greeted him like an old friend. It turned out they had met years before when Guy was taking a philosophy class at UCLA.

“Guy, it’s Jim.”

“You know me?”

“Guy, we went to UCLA together.”

“Oh my God. Jim!”

It was Jim Morrison, much thinner and with much longer hair than when Guy had last seen him in the classroom. The group, of course, was the Doors, and the album cover, dominated by Morrison’s handsome face, would earn Guy his second Grammy nomination.

“The Doors” was released in January 1967, and by June the single “Light My Fire” was igniting the charts. This was the eve of the Summer of Love, and the Doors clearly were going places — but they would not be going to the summer’s inaugural event, the soon-to-be-legendary Monterey Pop Festival, which took place that same June.

The festival was the brainchild of Guy’s L.A. circle — Lou Adler, John Phillips, Terry Melcher and others. The Doors, for whatever reason, were not invited to join the line-up. But Guy was invited to attend, in an official capacity. He had created the influential flowerchild image featured in the festival brochure, and he was there in person to shoot Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and the Who as they passed into legend.

In the wake of Monterey, Herb Alpert invited Guy to head up the art department at A&M Records. Guy accepted, in part because he could see that rock was now becoming a big business, which meant more corporate interference with the creative types. Photographers like Guy would henceforth have less control over their work. But A&M as an independent label employed fewer suits and could allow Guy more autonomy.

In her 2009 book “Who Shot Rock & Roll,” the photography historian Gail Buckland described Guy Webster’s 1960s oeuvre as “part of the collective unconscious of an entire generation. The look of a Webster photograph is the look of the period; he took the photograph of the gorgeous, seemingly naked blonde in a pool of water with flowers surrounding her that was the centerpiece of the brochure for the Monterey Pop Festival of 1967. He identified and isolated a look and an attitude, and then millions copied it. His photographic record of the sixties is as descriptive, in its own way, as Kerouac’s is of the fifties.”

During his rock ‘n’ roll heyday, Guy photographed an extraordinary range of notable recording artists. In addition to the above-mentioned legends, his subjects included Bob Dylan, Sonny and Cher, Paul Revere and the Raiders, Liza Minnelli, Nancy Sinatra, Chicago, Procol Harum, Nico, the Turtles, Carole King, Taj Mahal, Judy Collins, Waylon Jennings, Johnny Rivers, Sergio Mendes and Brasil 66, Captain Beefheart, Barbra Streisand, Earth, Wind & Fire, Randy Newman and Igor Stravinsky, along with many others.

(Local note: Guy created striking covers for the first two Spirit albums, both produced by Lou Adler. This band included former Ojai residents Ed Cassidy and his stepson Randy Wolfe, a.k.a. Randy California, along with future Ojai resident John Locke.)

One classic album cover Guy might have shot, but did not, was “Smile” by the Beach Boys, the projected follow-up to their classic 1966 album “Pet Sounds.” Nobody shot “Smile,” because the group’s resident genius, Brian Wilson, apparently had some sort of mental meltdown in the spring of 1967, and the much–anticipated album never came out, at least not as originally conceived.

Guy took many photographs of Wilson and the Beach Boys in the mid-1960s – he joined them on tour a couple of times, and he was there in the studio when they recorded the complicated vocal tracks for “Good Vibrations.” Brian Wilson paid tribute to Guy by writing the foreword to “Big Shots: Rock Legends and Hollywood Icons, The Photography of Guy Webster,” a lavishly illustrated, coffee-table book published in 2014.

“When Guy worked with us in 1966 and 1967 there were many different sessions with lots of different people on the dates, haunting the hallways,” Wilson wrote. “I was pretty focused on producing the music, so I was never certain where Guy was lurking, but man, he was right there.”

INTERLUDE: HELTER SKELTER

Back in the day, the Beach Boy whom Guy was closest to was not Brian but his younger brother Dennis, the group’s drummer. And it was through Dennis Wilson — and Terry Melcher — that Guy began hearing about an aspiring singer-songwriter named Charles Manson.

Manson was a creepy ex-con with a harem of young female runaways, whom he shared with Dennis in order to worm his way into the Beach Boy’s confidence. Thus did Manson penetrate the Hollywood rock ‘n’ roll world — Guy’s world.

“I was invited to Manson’s party at Dennis’s house in Pacific Palisades,” Guy says. “I didn’t go, but I heard all about it from my friend Ned Wynn.”

Wynn, the son of actor Keenan Wynn and the grandson of actor-comedian Ed Wynn, reported that Manson and his “family” had served up a sumptuous feast and then announced to their guests that all the food had been foraged from garbage dumpsters.

Terry Melcher did not attend that party either, but he was introduced to Manson another time, via a person who had met him through Dennis Wilson. As a producer, Melcher had a professional interest in cultivating new songwriters. Some authors who have written about Manson assert that Melcher initially was intrigued by the charismatic charlatan. Guy says these authors are mistaken.

“Terry wanted nothing to do with him,” Guy says. “He was too spooky and scary.”

But Manson evidently saw Melcher as his ticket to the big time, and was angry when Melcher declined to punch that ticket.

At the time, Melcher was living with the actress Candice Bergen in a rented house at 10050 Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon. (Guy says it was he who originally had set Melcher up with Bergen.) Guy himself never crossed paths with Manson at that house, or anywhere else. But he recalls attending a small dinner party there during which Manson’s name came up. Melcher and Bergen had only three guests that night: Guy and Bettie and Melcher’s mother, Doris Day. Melcher told them that Manson had been to the house, and that he (Melcher) was worried about what might happen. So he and Bergen were vacating the premises.

“Candice and I are moving to Malibu,” Melcher announced.

The address was a secret, Guy says: “Only his mother and Bettie and I knew.” Nevertheless, Manson somehow got wind of this move. He knew that Melcher had left Benedict Canyon behind. But Manson evidently wanted to send the producer a message. (And perhaps to touch off an apocalyptic race war while he was at it.) On Aug. 9, 1969, he sent his minions to the Cielo Drive house to kill whoever was there — which turned out to be Sharon Tate and her houseguests.

Guy was camping upstate amid the sequoias with Bobby Darin and their families when the news came over the radio about the mysterious slaughter in Benedict Canyon, at an address he knew very well. It would be months before police identified the killers, but Guy already had an inkling.

“I had a cognition — it could have been Manson,” he says.

All Hollywood was terrified.

“It put a damper on the wonderful ‘60s,” Guy says. “Everything was peace and light, and then you had this monster unleashed on the public. It scared everybody. People armed themselves.”

Guy bought a guard dog to protect his family, and Bettie took to wearing a .25 on her hip. (They and their three kids lived in Beverly Hills, not far from Benedict Canyon.) Terry Melcher hired armed guards to provide around-the-clock protection for himself and his movie-star mother, lest there be further depredations by murderous hippies. But it was melanoma rather than Manson that eventually claimed Melcher’s life, in 2004. (Doris Day is still very much with us, at 92.)

“Terry and I stayed friends ‘till he died,” Guy says.

EASY RIDERS, RAGING BULLS

Having taken over the record industry, Hollywood’s longhaired Young Turks next made their move on the movie industry. Older stars like Cary Grant and Elizabeth Taylor made way for the likes of Warren Beatty and Jane Fonda — and Jack Nicholson, whom Guy met in 1968 on the set of “Easy Rider.” Guy by this point had developed a sideline gig shooting celebrities for the Los Angeles Times, so it was a natural segue for him to shoot what were called “specials” for the film studios. His book “Big Shots” features Nicholson on its cover and plenty of other film stars inside, alongside the rockers.

(For an analysis of Guy’s approach to portrait photography, see Anca Colbert’s “Art And About” column in the Summer 2014 Ojai Quarterly.)

Guy had come full circle. Having grown up within the Hollywood world, he had returned to it in triumph. Rock stars now outranked film stars in terms of cultural prestige, so actors like Nicholson were eager to be immortalized by the same photographer who had shot the Doors and the Stones.

The irony is that by this point in his life, Guy was getting ready to leave the Hollywood scene behind. He had been working hard since he was a teenager. In 1971, he rented out his Beverly Hills house and took his family to Europe for what would turn out to be a very long break.

“I took off and I didn’t come back for five years,” he says.

Guy loved living in Florence and summering on Minorca, and he found plenty of professional work to sustain him in Europe. He also began acquiring Italian motorcycles at this time. But ultimately his marriage to Bettie foundered, so he returned to L.A. (and to Beverly Hills) in the mid 1970s to pick up the pieces. He got involved with the stylistically innovative WET Magazine (“The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing”), and he married the actress and model Leone James and began a second family. Which is what finally brought him to Ojai.

THE BRIDGE

Guy being Guy, the story he tells of how he and Leone got together is a long and compelling tale involving a Hollywood film premiere (“Superman,” 1978) and an ice-skating outing (with the Olympics gold medalist Dorothy Hamill, who later married Guy’s friend Dino Martin, a son of the film star Dean Martin who had given Guy one of his first motorcycles, but that’s another story). Suffice to say that he and Leone met, fell in love and began planning a life together.

“We didn’t want to raise children in Beverly Hills,” he says. They considered New Mexico and Oregon as alternatives. Then one day in 1979, Guy stopped off in Ojai while en route to Santa Barbara, and he happened to see the picture of a certain house on display in the window of a real-estate office in the Arcade. The house was on Reeves Road in the East End, and the driveway crossed a white bridge to get to the property. The bridge is what really caught Guy’s eye.

“I had a cognition,” he says. “I was supposed to buy this house.”

The house had started life as a barn on the old Soule Ranch (now Soule Park). Zadie Soule sold it circa 1948 to a Russian ballet dancer named C. Kahn Bashiroff, a Cold War defector who had settled in Santa Barbara and wanted a weekend home in Ojai. Bashiroff moved the barn to the Reeves Road lot and began converting it into a house. When Guy first encountered the structure three decades later, it still needed a lot of work. Undeterred, he bought it the very next day, and he and Leone moved in in 1980.

“We spent 20 years remodeling it,” he says.

At first they just spent weekends here. But the people they met in Ojai were interesting and the valley was beautiful, so they found themselves spending more time up here. “When the kids came along, we just stayed,” he says.

And so Guy Webster finally left Beverly Hills behind him for good, and put down roots in Ojai. His and Leone’s two daughters, Jessie and Merry, attended the Oak Grove School. Many friends from L.A. who came to visit were inspired to buy houses here too, he says, mentioning Mary Steenburgen, Malcolm McDowell and Peter Strauss among others. Meanwhile Guy continued to work as a photographer, commuting via motorcycle to his studio in Venice.

Thirty-six years have passed since Guy moved here, and he has long since become an Ojai institution. The girls grew up and moved away, but he and Leone remain. (No longer on Reeves Road, but still in the East End.) They have houses elsewhere and spend a fair amount of time on Martha’s Vineyard, but for Guy, Ojai is home.

ZEN, MOTORCYCLES, MAINTENANCE

Guy took a career victory lap in November 2014 when Insight Editions published “Big Shots: The Photography of Guy Webster,” which won much applause and several awards. But four months later he landed in the hospital for quadruple-bypass surgery. The operation on his heart was successful, but it triggered a stroke that put him in a wheelchair. No more tennis, no more golf, no more riding his motorcycles, no more taking photographs.

“But I can talk,” he says cheerfully.

He concedes that he wasn’t this chipper in the immediate aftermath of the stroke. Having led a charmed life for so long, he faced a difficult adjustment to his new reality.

“I was very depressed and angry, but I kind of thought that this was a lesson for me,” he says. “My life was so perfect from the cradle to the wheelchair. Now I had to learn how to live as an invalid.”

Not that he accepted that he would remain one. He made considerable progress toward recovery before a fall down some stairs put him back in the wheelchair. Now he is once again out of the chair and using a walker and progressing toward a cane. He hopes eventually to regain his ability to operate a camera, but he knows he may never again ride one of his bikes.

“It was like my church to get on a motorcycle and ride out into the wilderness,” he says. “To have it taken away was frightening.”

Guy says he relies on the Buddhist philosophy of non-attachment to help adjust himself to his new circumstances. He has given up his photography studio in Venice, and he continues to sell off his motorcycle collection. But he has his wife and his children and grandchildren and his many friends, and he is content.

“I’ve always had Buddhist leanings, all my life,” he says. “You have to make the little things in life just as important as the big things.”

Leave A Comment