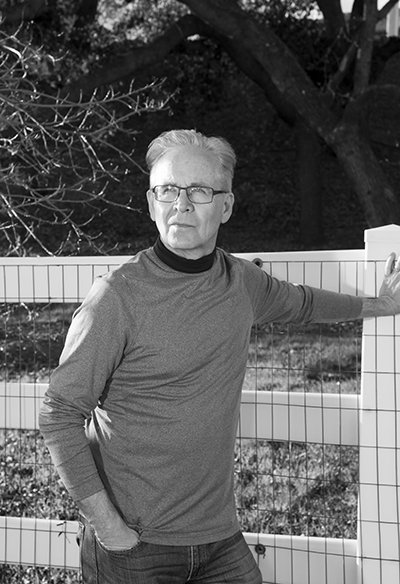

By Mark Lewis

Ojai writer Mark Frost worked with David Lynch on the acclaimed sequel to their classic television series “Twin Peaks,”

set in a small town in Washington state. But Frost’s next writing project will be set in a different small town: Ojai.

When Mark Frost moved to Ojai five years ago with his family, he was not quite sure what he was getting into.

“I’d always been a big-city guy,” Frost says. “I didn’t know what to expect.”

The only small community Frost really knew well was Twin Peaks, the fictional setting of the classic 1990s television series of the same name, which he co-created with David Lynch. Twin Peaks is an idyllic-looking place – until Frost and Lynch pull back the veil to reveal a surreal snake pit full of psychotic drug dealers, greedy intriguers, and murderers possessed by evil demons. A person nowadays who binge-watches “Twin Peaks” on Netflix might easily develop an aversion to small-town living.

But to Frost, Ojai is the opposite of Twin Peaks.

“There’s something very special here,” he says. “There’s a kind of magic that you rarely find in other places.”

Nevertheless, Frost has been spending a lot of his time in Ojai thinking dark thoughts about strange doings. The explanation is simple: He and Lynch were writing a “Twin Peaks” sequel, which will feature many of the original cast members, including Kyle MacLachlan as FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper. Currently in production with Lynch as director, the sequel is scheduled to debut early next year on the Showtime premium cable network.

So the fictional town of Twin Peaks is much on Frost’s mind these days — but then so is Ojai, which will figure prominently as a setting for his next project, a book about Krishnamurti. Nor will that be the first book Frost has set in this valley. He may only have lived here for four years, but in a way, his association with Ojai goes back four decades, to the very beginning of his career.

BACKSTORY

Frost was born in Brooklyn in 1953, and grew up in New York, Southern California and Minnesota. His father was an actor and his sister became one too, but Frost would rather put his own words on paper than read someone else’s aloud.

“I knew I was going to be a writer by the time I was 7,” he says.

After spending two years in a high-school internship program at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Frost enrolled in the drama program at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, with the goal of becoming a playwright. But in the summer of 1974 he took a break from his studies and went out to L.A., where a Carnegie Mellon alum named Charles Haid introduced him to another alum, Steven Bochco.

Bochco at the time was story editor of “McMillan and Wife,” a TV series starring Rock Hudson that was produced by Universal Studios.

“He got me in at Universal,” Frost says.

As a result, Frost stayed in L.A. and launched his career by co-writing two episodes of the Universal series “The Six Million Dollar Man.” It starred Lee Majors as Steve Austin, an astronaut-turned-cyborg who, per his backstory, had grown up in Ojai. (The town would figure even more prominently in a spin-off series, “The Bionic Woman.”)

“It’s almost like it was foretold that I was going to end up here,” Frost says.

It did not seem that way at the time, however.

“I was aware that the show had an Ojai connection – it was mentioned in the scripts – but it made no impression on me,” he says. “At the time, I don’t think I even knew it was a real place.”

Then he began hearing about Ojai in a different context.

“My interest in Krishnamurti and Theosophy dates to the ‘70s, under the category of ‘spiritual curiosity’ for a young adult who was decidedly non-religious by nature and nurture,” Frost says. “K was still speaking in Ojai and I did have a couple of close friends who attended lectures in the Oak Grove, but regrettably I never made the trip.”

Still set on becoming a playwright, Frost returned to the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, where he was a “literary associate” for several years. But he kept in touch with Bochco, who meanwhile had gone on to develop a groundbreaking police drama, “Hill Street Blues,” which debuted in 1981. (The cast included Charles Haid as Officer Andy Renko.) Bochco lured Frost back to L.A. to join the writing staff starting with the third season, and Frost worked on 35 episodes as a writer and/or story editor.

“Hill Street” was an enormously influential show. With its large ensemble cast, its gritty themes, its realistic sets and exterior locations, and its use of sophisticated cinematic techniques (including handheld cameras), the show looked and sounded like nothing else on TV.

Another innovation was its complex narrative approach: “Hill Street” featured multiple story lines, many of which unfolded from week to week instead of being wrapped up neatly within each hour-long episode. During its seven years on the air, the series racked up 98 Emmy nominations (including one for Frost) and a record 26 wins.

“It was a hell of a ride,” Frost says.

The “Hill Street” writers’ room constituted a challenging, competitive, high-pressure environment, where Frost had to keep up with the likes of David Milch (who went on to fame with “NYPD Blue” and “Deadwood”) and Anthony Yerkovich (who went on to create “Miami Vice”). To decompress, Frost liked to get away from Hollywood occasionally to relax on a golf course. As it happens, there was a good one in Ojai.

By this point, Ojai was no longer the make-believe home of the Six Million Dollar Man and the Bionic Woman. But it was the real-life home of Linda Kelsey, an old friend of Frost’s from Minneapolis (and an Emmy-nominated actress on “Lou Grant”).

“I remember her telling me about it,” Frost says. “I started coming up here to play golf at the Ojai Valley Inn. Who knew that that would end up being my home course?”

After three years on “Hill Street,” Frost tried his hand at screenwriting, and he began to incorporate supernatural elements into his scripts. Among his early efforts was “The Believers,” adapted from a novel about a murderous voodoo cult. “The Believers” was produced and directed by the noted filmmaker John Schlesinger, with Frost serving as associate producer and directing some of the second-unit work.

“That was sort of my master’s education in filmmaking,” he says.

It was around this time that Frost began working with the writer-director David Lynch. Best known at the time for “Eraserhead” and “The Elephant Man,” Lynch was wrapping up work on “Blue Velvet,” and preparing to make a film about Marilyn Monroe. The script was to be adapted from “Goddess,” a recently published Monroe biography.

“David and I were introduced by a mutual agent of ours at the time, who thought we would hit it off on the Monroe project,” Frost says. “We met over coffee and did hit it off and went from there. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what makes a creative match like that persist other than chemistry and affinity and, as it turned out over the long haul, tolerance, friendship and success.”

The Monroe project didn’t pan out. But Frost and Lynch went on to collaborate on a script called “One Saliva Bubble,” a comedy about two sets of twins and switched identities. Steve Martin and Martin Short signed on as the stars, with famed producer Dino de Laurentiis providing the funding. Frost says they were only a few weeks away from production when the De Laurentiis production company went bankrupt., pulling the plug on the film.

Next, the ABC network suggested that Frost and Lynch try their hands at creating a television series. The result was “Twin Peaks.”

The two-hour pilot episode aired on April 8, 1990, and created an immediate sensation. Co-written by Frost and Lynch and directed by Lynch, it introduced MacLachlan as Agent Cooper, who arrives in Twin Peaks to investigate the murder of a local high-school student named Laura Palmer. Twin Peaks is a small community surrounded by a thick forest, which hides many secrets. Cooper soon finds that nothing in this bucolic-looking town is as it seems.

As the series unfolded during the first season, the clues lead Cooper to a supernatural suspect, a demon who has possessed a local resident. But which one? Viewers tuned in week after week hoping to find out who – or what – had killed Laura Palmer.

“We were trying to do something a little different,” Frost says.

They succeeded, and then some. “Twin Peaks” was unlike anything seen on TV before. Like “Hill Street Blues” before it, but to an even greater degree, “Twin Peaks” was novelistic and cinematic. It was also deeply, compellingly weird.

Frost and Lynch took a surrealistic approach to storytelling, grafting dream sequences and otherworldly elements onto their murder-mystery plot. On one level, the show came across as a parody of a genre that did not actually exist: the horror soap opera. But on another level, “Twin Peaks” was genuinely scary. It was smart and funny and creepy and disturbing, all at the same time. It caught America’s imagination and became a cultural phenomenon, the sort of hit show that everyone talks about, whether they watch it or not.

Lynch was a recognized film auteur, and “Twin Peaks” seemed to be of a piece with “Eraserhead” and especially with the much-celebrated “Blue Velvet.” But Lynch was not involved in every episode. He had other irons in the fire, such as directing the film “Wild At Heart,” while Frost, as the “Twin Peaks” show runner, kept his hand on the tiller. When the show took off, both co-creators found themselves in a powerful media spotlight.

“It was like hanging on the end of a rocket,” Frost says.

In addition to its edgy themes and artsy affect, “Twin Peaks” stood apart for its long-form approach to storytelling. At the end of the first season, viewers still did not know who had killed Laura Palmer.

“Long-form drama was always very compelling to me,” Frost says. “I felt we could take it further.”

Ultimately, they may have taken it too far, at least for TV audiences of the time. Halfway through the second season, under pressure from the network, they finally identified the killer. After that, some of the audience faded away, in part because ABC kept moving the show to different time slots, and in part because it was frequently pre-empted by coverage of the Persian Gulf War.

“The wind went out of the sails,” Frost says.

Amid diminishing ratings, the season ended with a cliffhanger episode designed to pique viewers’ interest in Season 3. But at that point, ABC pulled the plug. There would be no third season, and no plot resolution. Nevertheless, “Twin Peaks” already had made a permanent mark on the culture. Frost suspected as much, even at the time: “I felt like we were building something that might last.”

He was right. “Twin Peaks” has endured, and not just as a fondly remembered cult classic. Cultural historians regard it as a milestone television event that paved the way for the sophisticated, challenging, novelistic shows that have flourished since the advent of cable – shows like “The Sopranos,” “Mad Men,” “Breaking Bad” and “True Detective” (the latter created and written by Ojai resident Nic Pizzolatto). In short, “Twin Peaks” was important, and it represents a career peak for the team that created it.

“We all realize this is going to be the first line in our obituaries,” Frost says. And that’s OK with him: “Everybody wants to be remembered for something. It may as well be this.”

PLAN B

After “Twin Peaks,” Frost co-wrote and directed “Storyville,” a 1992 movie starring James Spader. But he also started writing books, both fiction and nonfiction, and these days he views himself primarily an author rather than a scriptwriter.

“That was Plan B,” he says of book writing. “I now consider that my primary career.”

His first novel, published in 1993, was an occult murder mystery called “The List of Seven” that featured Arthur Conan Doyle as a protagonist, with Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy, in a supporting role.

“I started writing ‘The List of Seven’ right after ‘Storyville’ – another disillusioning experience in the Hollywood shark tank, this time as a director – so Plan B was officially launched at that point,” Frost says.

Nevertheless, he continued to work for the studios as a screenwriter for hire for the next dozen or so years, to pay the rent while he developed his book-writing career. (His screen credits during this period included the first two “Fantastic Four” films, based on the Marvel comic book series.)

“It’s a terrible way to make a terrific living,” he says. “As Oscar Levant — or maybe it was Dorothy Parker — once said: The thing about Hollywood you have to understand is, underneath all that tinsel is real tinsel. The impulse to write books harkens back to why I originally chose to be a writer instead of an actor: the overwhelming desire to be able to speak, and write, in your own voice. “

He now has seven novels to his credit. (His most recent effort, published last fall, was “Rogue,” the third installment of Frost’s “The Paladin Prophecy” series for young-adult readers.) As for his four nonfiction books, they have all been inspired by historic sports contests. They include “Game Six,” about the epic sixth game of the 1975 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and the Cincinnati Reds; and “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” about the 1913 U.S. Open, during which a young, unheralded American amateur defeated the famous English professionals Harry Vardon and Ted Ray in a playoff.

In 2005, Frost adapted “The Greatest Game” as a screenplay and then co-produced the film version, which was directed by Ojai’s own Bill Paxton. Paxton’s friend and fellow Ojai resident, the artist Mick Reinman, served as a visual consultant. And that was how Frost eventually found his own way to Ojai as a permanent resident.

“We really bonded on the movie and became really good friends,” Frost says. “I have to give Bill Paxton and Mick Reinman a lot of credit for beguiling us with tales of the Ojai while we were making the picture, which led directly to our exploratory interest here.”

Frost and his wife, Lynn, were looking to escape from L.A. and raise their son, Travis, in a child-friendly environment. Lynn grew up in a small town in Tennessee, so she was primed to embrace Ojai. Frost, a city boy, was more hesitant about settling full-time in such an out-of-the-way place. His ambivalence seems to have colored the first installment of his “Paladin Prophecy” series, which he was writing at the time. The book begins in Ojai, where teenager Will West and his parents recently have settled:

“After only five months here, he liked Ojai more than anywhere they’d ever lived. The small-town atmosphere and country lifestyle felt comfortable and easy, a refuge from the hassles of big-city life.”

But, this being a Mark Frost novel, sinister machinations are stirring beneath the town’s placid surface. Will detects intimations of a “queasy cocktail of impending doom,” which haunts him like “the hangover from a forgotten nightmare.”

Unsurprisingly, the move to Ojai ends badly for the Wests. But that did not deter the Frosts. The turning point came one day during a scouting expedition, when Mark and Lynn were driving around the East End and they passed three teenage girls walking along the road. The girls did not know the Frosts, but they smiled and waved, as people do in a friendly small town. That was enough for Lynn.

“She turned to me and said, ‘We’re moving here,’ in a way I knew better than to argue with,“ Frost says.

Continuing on their drive, they ended up at the end of Thacher Road, where they encountered a sign that was a sign in more ways than one: “Twin Peaks Ranch.”

That did it: “Six months later, we were here.”

Four years later, all three Frosts have taken root. Travis attends the Ojai Valley School, and Mark and Lynn are big supporters of the Ojai Valley Defense Fund.

Ojai reminds Frost of the Southern California he fondly remembers from his childhood during the 1960s, before most of the orange groves were paved over for shopping malls.

The idea behind the Defense Fund is to amass a war chest big enough to deter mining companies and big-city developers, and thus to preserve Ojai as a pristine rural paradise.

“I don’t know of any other town that’s taking these steps to defend itself” from encroachment, Frost says. “It’s the walls of Troy!”

If Frost needed a sign that moving to Ojai had been the right decision, he found one shortly after he settled here, while he was playing a round at the Inn. Arriving at the 13th tee, he encountered a commemorative plaque that he had never noticed before, which highlighted two very familiar names. The plaque informed Frost that when the Inn (then called the Ojai Valley Country Club) first opened in 1924, Harry Vardon and Ted Ray played an exhibition match there. Having already written both a book and a movie featuring these two English golfing legends, Frost now found himself literally following in their footsteps.

“I have this secret theory that all roads lead to Ojai,” he says. “Every time I start down a path, it leads me here.”

He encountered yet another sign in the Summer 2013 issue of The Ojai Quarterly, which featured an article about Thornton Wilder’s time as a student at The Thacher School. Wilder is one of Frost’s favorite writers, and “Our Town” is his favorite play, so he was fascinated to read that Ojai — or Nordhoff, as it was then known — may have been the original model for Grover’s Corners, the small town where Wilder set the play.

Whether it’s Wilder or Krishnamurti, or Vardon and Ray, or even Steve Austin of “The Six Million Dollar Man,” Frost keeps turning up Ojai connections that long preceded his arrival here as a full-timer.

“This place has been calling me for a long time,” he says. “I’ve never felt as much a part of a community as I do here.”

BACK INTO THE FOREST

More recently, another community has been calling to Frost, the one he and Lynch invented: Twin Peaks. People who watched the original show still recall it vividly, and it has won new fans over the years via video rentals, cable reruns and Netflix streaming. Meanwhile, cable television evolved to the point where today it offers a vastly more hospitable environment for Frost and Lynch than they found on broadcast television back in the early 1990s. Eventually it occurred to them that the time was ripe to have another go at it.

In a way, Lynch had given it another go back in 2001, when he created “Mulholland Drive” as the pilot for a proposed ABC series.

“It began, much earlier, as a piece we were going to do as a ‘Twin Peaks’ spinoff, following the Sherilyn Fenn character, Audrey Horne, to Tinseltown,” Frost says. “Although I ultimately was not involved with either the pilot or film, I was living on Mulholland Drive at the time, and that’s the title comes from.”

By 2001, the concept had evolved to the point where it was no longer a “Twin Peaks” spinoff per se, although stylistically and thematically reminiscent of the earlier show. But ABC passed on the series, so Lynch completed the pilot as a feature film. Released by Universal, it made a star of Naomi Watts and earned Lynch a best-director Oscar nomination (his third). Yet he remained interested in exploring the long-form possibilities unique to television.

It took another decade, but TV culture finally caught up with “Twin Peaks.”

“David and I always stayed in touch,” Frost says. “We suddenly looked up and realized that it’s back in the zeitgeist.”

They devoted two years to writing one long script, which Lynch is now filming, with himself and Frost as co-executive producers (and with Naomi Watts reportedly among the new cast members, although Frost would not confirm this). When this epic movie is in the can, it will be carved up into multiple episodes, the exact number of which has not yet been determined.

This process represents the culmination of a career-long progression for Frost, from the single-episode story arcs of “The Six Million Dollar Man,” to the multi-episode arcs of “Hill Street Blues,” to the season-long arcs of the original “Twin Peaks,” to the series-long arc of the sequel, which Showtime is billing as a “new limited series.”

“It’s not a reboot,” Frost says. “It’s the story in continuity.”

Currently, Frost is writing a companion novel, “The Secret History of Twin Peaks.”

“I’ve just finished the first draft,” he says. “It goes back to the 18th century and weaves the tangled, mysterious history of the town, its people and the region, up through and including the events of the old series.”

He expects to publish the novel this fall, ahead of the new series premiere early in 2017.

Given that Frost was living here while he was writing the “Twin Peaks” sequel, will local residents who watch the show be able to detect some echoes of life in Ojai? Frost says that he did not consciously draw upon Ojai while recreating Twin Peaks. But he concedes that he might have done so unconsciously, because writers tend to be inspired by their surroundings, and he finds Ojai inspirational on many levels.

“It can’t help but show up in the new series,” he says. “I’ll leave it to others to figure out how that manifests itself. But that’s probably inevitable.”

THE POWER OF MYTH

Novels, nonfiction narratives, feature films, epic TV extravaganzas: As a storyteller, Frost is associated with just about every long-form format except the one he started out to hoping to master. Will he ever go back to writing plays?

“It’s on my bucket list, I’ll put it that way,” he says. “But if you’re a born storyteller, the format shouldn’t matter. You’ll be drawn to the process of storytelling, the way we’re all drawn to water.”

Frost will stick with the book format to tell his next story, that of Krishnamurti. He has not yet decided whether to write it as a novel or as a nonfiction book, although he’s leaning toward the hybrid approach, also known as the nonfiction novel, which Truman Capote pioneered with “In Cold Blood:”

“I’m not far enough into the work yet to say definitely which approach I’ll end up using,” Frost says, “but such a remarkable human story will dictate the style and form of the storytelling, and a hybrid approach feels now like the most appropriate.”

Frost’s narrative will follow Krishnamurti from his childhood in India, where Theosophists identified him as their future World Teacher, through his early years in Ojai, where he found a lifelong home, to the pivotal year 1929, when he rejected the messiah role and choose the philosopher’s path instead.

Along the way, Krishnamurti encountered and befriended Joseph Campbell, who will figure prominently in Frost’s book. Meeting K turned out to be a milestone on Campbell’s path to the mastery of comparative mythology.

“For me, Campbell is one of the century’s most influential thinkers, and having an opportunity to depict the way in which their paths crossed with such lasting impact is tremendously appealing,“ Frost says.

In his 1949 book “The Hero With a Thousand Faces,” Campbell identified what he called the monomyth, common to all cultures: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

If that sounds like a description of Agent Cooper venturing into the supernatural precincts of Twin Peaks, it’s not a coincidence. (To find out whether Cooper wins a decisive victory, we’ll have to wait for the sequel.)

Campbell’s explication of the monomyth, also known as “the hero’s journey,” is an idea that has launched a thousand plots, including the one George Lucas devised for “Star Wars.” Frost embraces Campbell’s concept with enthusiasm, on both a personal and a professional level.

“Look, at a certain point you can realize that all of life is both literal and metaphorical, and that approaching or perceiving your own journey through the lens of myth and narrative brings enormous benefit, insight and enrichment to the experience of being alive,” he says. “We need to feel connected to myth. And that’s the job of the storyteller. We’re the intermediaries.”

It’s a job Frost takes very seriously. “It’s a sacred role,” he says. And there’s no better place to perform it than here in Ojai:

“The idea of the single myth appeals to me far more than any sectarian or mediated truth,” he says. “That’s also a central tenet of K’s message, as well as Campbell’s, and that’s also in some way an essential part of Ojai’s appeal as a place.

“All these myths are free to live and thrive here, in equal measure, with none trying to crowd or drown out another. It’s a model of tolerance, civic responsibility and self-reliance that offers something like a way forward at what feels like a decisive moment for our troubled and quarrelsome species. I think truth, as K famously said, really is a pathless land. You won’t find it on a map, but you just might find it here.”

Leave A Comment